Mandy Lane with Professor Kirsti Bohata is Mandy Lane‘s final piece and podcast for Wales Arts Review’s new series, Artists in Residence. Throughout 2017 artists, including Mandy Lane will take a leading creative role in what Wales Arts Review publishes, centring their skills on a challenging project over the course of a month. We were inundated with applications, receiving hundreds of emails about the positions, and it was no easy task whittling down all that talent to this final eleven. Our team of six editors debated long into the night, and in the end, we decided on a collection of people who we most want to work with, and whose work excites us. We think you will be excited by them too.

In this conversation podcast for her final piece for her Wales Arts Review residency, Mandy Lane discusses her project with leading Amy Dillwyn expert, Swansea University’s Professor Kirsti Bohata. And by scrolling down you can move through an accompanying photo essay of all of Mandy’s artwork that is discussed in the podcast.

On the 29th of March 2017, I invited Professor Kirsti Bohata to discuss my works created in response to the life and fiction of Amy Dillwyn during my Wales Arts Review residency. Professor Bohata has played an integral role in my understanding and research of this inspirational woman; and the immense value of her enthusiasm, knowledge and support cannot be understated.

The podcast Mandy Lane with Professor Kirsti Bohata is available to listen to via Wales Arts Review’s official Soundcloud profile. Other podcasts by Mandy Lane as part of the Artists in Residence series are also available, as well as other audio-based content by other artists.

Le jeu ne valait pas la chandelle

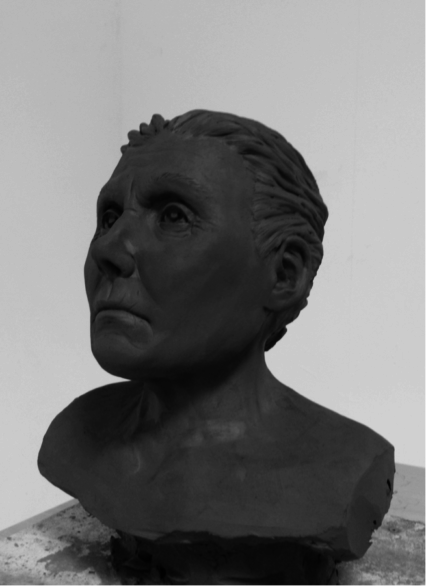

Le jeu ne valait pas la chandelle was the first piece of work created in response to the life and fiction of Amy Dillwyn. The piece considers the death of Llewellyn her fiancé, and arguably the liberation of Amy from the life of marriage. The body is dressed replicating a funeral described in the novel Jill, embracing the stripped-back simple nature of death in contrast to the Victorian obsession of the time. Death also seemed integral to her liberation from the societal restraints upon women, and also recognition of her individuality.

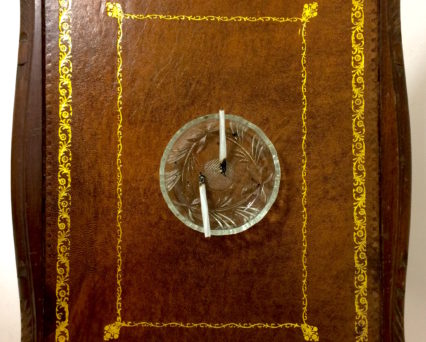

The Iron on the Dress is in response to Amy Dillwyn’s first steps of divorcing societal restraints and expectations. Many times she refers to herself as molten metal, a furnace. The act of pouring metal over the dress alludes to the developing world of industry in Amy’s later life and the breaking out from conforming, moving from the path that was set onto one of her own makings, and the celebration of this road she carved for herself.

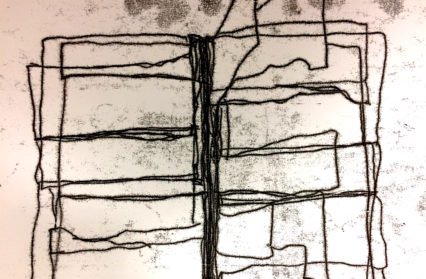

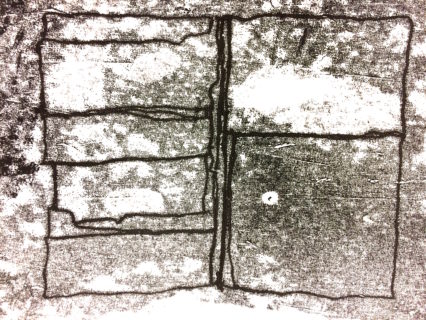

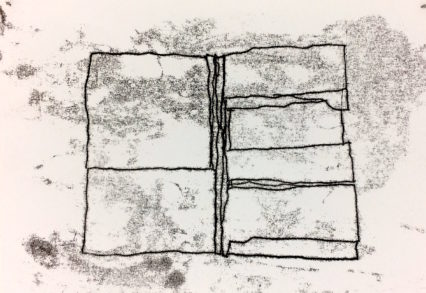

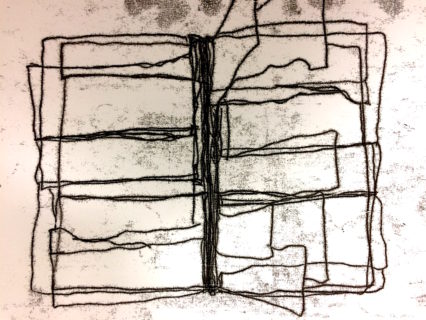

The Pieces Of Me.

Amy Dilwyn kept diaries throughout her life. The Pieces of Me are mono-prints of one personal diary that had large sections cut out. In removing these pieces, Dilwyn appears to be editing herself from or for herself.

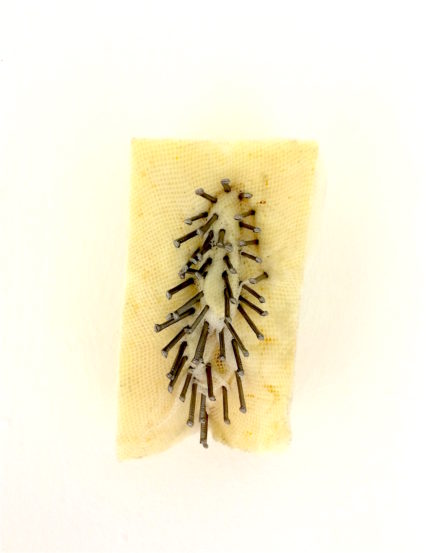

Amy often used clothes to illustrate limits and cultural restraints. This was evident in the novel Jill, both when the character Kitty needed to remove her clothes to escape from her captives, and also when Jill wanted to play mud-larking as a child. In both circumstances, she removed the debilitating factor, her clothes. In these pieces, I took this literally and removed parts of the 100-year-old wedding dress and nailed the fabric to body parts illustrating the cultural restrictions Amy alludes to in the form of clothes. These were later cast in iron.

“Take me as you find me; if there’s no harm in it then there is nothing wrong with it. And I am not ashamed of being myself.” Amy Dillwyn, Painting (1987)

Cover her up

‘Cover her up’ is a response to this short story told in a time when marriage and children were the only way and anything else was considered a wasted life.

The short story The Buddhist Priest’s Wife written by Olive Schreiner (1855-1920) is arguably a conversation between the socio-culturally constructed genders portrayed through an intimate dialogue between the female protagonist and her male counterpart in which one is saying goodbye to the other. In this exchange, both characters smoke consistently and discuss the reasons for the protagonist’s imminent departure. The pair discuss societal life, marriage and death with their regards to how these are affected by their respective genders. The cultural patriarchal ideal that women should marry, have children and be subservient to men is challenged by the woman. This sentiment is encapsulated when the woman talks of the liberation from her sex through the act of death.

“Death means so much more to a woman than a man; when you knew you were dying, to look round on the world and feel the bond of sex that has broken and crushed you all your life gone, nothing but human left, no woman any more, to meet everything on perfectly even ground.”

This is the final contribution by Mandy Lane as part of the Artists in Residence series.