Craig Austin reviews A Poet in New York, Andrew Davies’ fictionalised account of Dylan Thomas’ experiences in the eponymous city, directed by Aisling Walsh and starring Tom Hollander, Essie Davis and Ewan Bremner.

The White Horse Tavern in Manhattan’s now fashionable West Village remains a steadfast municipal fixture, existing almost in defiance of the relentless march of 21st century gentrification that perpetually circles it, vulture-like and unremittingly ravenous. Yet as the sun begins to set, its loyal daylight clientele of ageing blue-collar raconteurs gradually makes way for a younger, less faithful, more affluent crowd; the kind of patron who thinks nothing of casually dropping $100 on a round of drinks or who cares little, or is even aware, of the bar’s towering literary heritage – a rich cultural inheritance that incorporates Ginsberg, Kerouac, and the now infamous final days of the iconic Welshman whose face intermittently peppers its walls and whose name is etched into a single plaque that sits above the bar; a plaque commemorating his final notorious visit.

‘This is a proper pub’, the writer proclaims in one of A Poet in New York’s earliest scenes, his tie dangling, his ruddy face wet and puffy, ‘like a Swansea pub’. The award-winning screenwriter Andrew Davies’s dramatisation of Dylan Thomas’s final days in New York City, has swiftly established itself as one of the BBC’s most anticipated dramas of recent years, generating much online discussion about the intriguing casting of Bristolian Tom Hollander (TV’s Rev) in its lead role. Flitting between 1950s New York and Laugharne, Thomas’s Carmarthenshire home for the latter years of his life, the entire production was shot in just 18 days and filmed entirely location in Wales; yet despite the requirement to operate within restrictive budgetary limitations the authentic sense of place and of era that it succeeds in evoking is a truly captivating spectacle.

Beginning on 20th October 1953, the date upon which the poet arrived in “’his fabulous filthy city’ for the fourth and final time, we are introduced to Hollander’s Thomas, suitably portly on account of the actor having gained a hefty amount of weight in order to play the part, in the arrivals area of NYC’s Idlewild airport. Ostensibly in town to write, rehearse, and embark upon an onward westward journey to rekindle a creative relationship with Igor Stravinsky – an irresistible ‘what might have been’ – Andrew Davies’s exploration of Thomas’s descent into the spiral of his own demise, his untenable grasp upon the realities of adult life, swiftly commences; the ironic protestations of the writer about a flight spoiled by a ‘roaring drunk’ passenger laying the foundation for an ultimately tragic tale of self-delusion and wanton excess – a personal crusade of random adultery and fatal alcoholic gluttony.

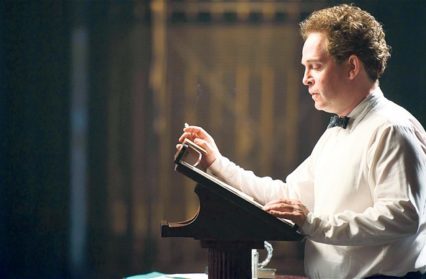

Hollander is strangely compelling in the lead role, the voice sufficiently faithful, the chaotic sense of mischievous lawlessness intact. His most compelling scenes however take place under the residual effect of Thomas’s alcoholic excess; his hungover yet captivating oratory beguiling the spellbound faces of his adoring East Coast fans (a series of beautifully shot scenes filmed in Cardiff’s New Theatre). His portrayal of Thomas is one purposefully steeped in the writer’s impulsive and mercurial nature, an anarchic almost childlike sense of urgency often overlooked by those who have subsequently sought to depict Dylan Thomas in more earnest, more solemn, more worthy tones. It is an approach that works especially well when seeking to expose Thomas’s unsophisticated and boorish limitations; his failure to engage with women in anything other than the manner of a lusty teenage boy, his responsibilities as a husband and father that appear to swiftly evaporate beyond the periphery of the family home. Thomas’s childhood, his torment and bullying at the hands of local children, is revisited here in repeatedly raw yet fleeting flashbacks. Recollections brutally etched into the poet’s psyche and ones that recurrently rise to the surface in the darker moments of his adult existence. Childhood nags at Hollander’s Thomas, yet comforts him with its cosy familiarity nonetheless.

In a pivotal scene in which the adult Dylan feasts on a bowlful of bread chunks steeped in milk – an infant’s meal – his own father’s frustration at his wife’s easy willingness to accommodate their son’s most childlike of foibles is palpable. Where Andrew Davies truly excels is in his successful positioning of Thomas as a man perpetually tossed around within a transatlantic maelstrom. In this sense, the parallels between the magnetic pull of New York City and its attendant undiscovered urban beauties, and his chaotic family home set amongst its tranquil unobtrusive splendour of Laugharne, are clearly drawn. Essie Davis, as Thomas’s long-suffering, yet equally belligerent, wife Caitlin, is the real revelation here however. Though the true nature of Caitlin Thomas’s own boozing and promiscuity is somewhat shrouded behind a film-maker’s veneer of intermittent domestic and matrimonial servitude, Davis nevertheless presents her as a tinderbox of raw emotion and terminal frustration, the collision of her inner rage and compulsive sense of injustice culminating in a powerfully poignant, yet utterly chaotic, death-bed scene that injects a jarring shot of militant Welsh fury into the starched collared conservatism of 1950s midtown Manhattan.

This biopic has its flaws admittedly, the intended sense of foreboding and its recurrently trailed snippets of forthcoming tragedy are occasionally overcooked – an early Manhattan bar conversation in which Thomas announces that he does not expect to reach the age of 40 feels particularly heavy-handed – and where Hollander’s lightness of touch works well in the main it has the tendency to veer into slapstick. Not least in Thomas’s notorious return from The White Horse Tavern, a scene in which Hollander’s bard feels it necessary, in a Fast Show-style ‘very, very drunk’ way, to proclaim that he had just consumed the now legendary eighteen glasses of whiskey. These are minor flaws however, in what only the most forensically focused of the poet’s acolytes could deny is a worthy addition to the canon of Dylan Thomas biopics. Coming as it does, in the centenary year of Thomas’s birth, and only a short time before the cinematic release of Andy Goddard’s Set Fire to the Stars – another dramatisation focused on Dylan Thomas’s final days in New York – this is a production of which the BBC (much like Thomas himself, a flawed work of genius) should feel justifiably proud.

Recommended for you:

Often revered as one of Wales’ greatest poets, Dylan Thomas lives on through his timeless and often moving collection of work. These articles provide a holistic view of the impact Dylan Thomas had, and still has, on the literary world.

Craig Austin is a Wales Arts Review senior editor.