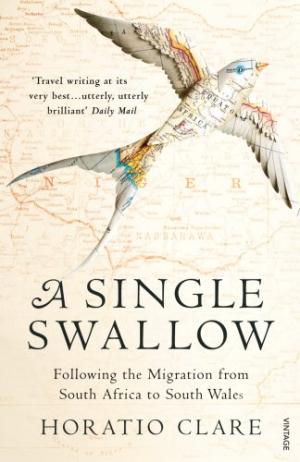

Adam Somerset revisits, and finds much to appreciate in, Horatio Clare’s first book, A Single Swallow, six years on.

Last year a swallow made a part of our home its own home for the summer. On occasion we would look up and see a small head on a rafter peeping over its construction of twig and wattle. Of swallows I knew nothing except that they moved at speed. Thanks to Horatio Clare and his extraordinary pursuit of his title subject I know a whole lot more.

I know now where our small resident of the summer months went. The flight south is a rough course from Brighton to Barcelona to Cape Town with a corner cut around the Gulf of Guinea. Some take the route down the Italian peninsula. For the longer sea crossing swallows build up reserves and add thirty to forty percent to their weight. The same build-up of fat reserves takes place for the journey north. To get across the desert requires unbroken flight of fourteen to sixteen hours. The birds that arrive in southern Europe are down to their last half-gram of fat.

In Zambia Clare reaches latitude twelve south where the plateau drops to equatorial forest. The routes north for the swallows divide in three; to the east the Nile Valley and the eastern Mediterranean, to the west entering Europe over the Straits of Gibraltar or due north over the widest stretch of the Sahara. A swallow of longevity is known to have reached ninety-six thousand miles of intercontinental flight in its lifetime.

Travel writing nudges at the other literary genres. It nips at the edges of history and autobiography. The Clare personality that emerges is engaging, vulnerable, open-hearted. He is briefer on history than some, crisp on the concentration camp state that William Henry Stanley made of an entire country at the behest of his abhorrent master in Brussels. He omits Philip Morrell who blew the lid off the horror that was Belgium’s Congo.

Travel writing nudges at the other literary genres. It nips at the edges of history and autobiography. The Clare personality that emerges is engaging, vulnerable, open-hearted. He is briefer on history than some, crisp on the concentration camp state that William Henry Stanley made of an entire country at the behest of his abhorrent master in Brussels. He omits Philip Morrell who blew the lid off the horror that was Belgium’s Congo.

But Clare has done his reading. Chaucer’s “Parlement of Foules” is a “poetic tour around the Garden of Love.” With the Roman general Scipio Africanus as his guide Chaucer’s hierarchy places the swallow between the nightingale and the turtle-dove. Shakespeare draws from Plutarch and notes the presence of swallows nesting under the prow of Cleopatra’s flagship before the battle of Actium.

In the iconography of tattoos a swallow on a sailor means five thousand miles travelled at sea, an occasional second swallow ten thousand miles. Clare touches on the sexual habits of his birds. Male display comprises “soaring and diving above their territory, singing and flaunting their tails.” If a female takes the cue “the male will land, fan his tale, give his enticement call and point out his suggested nest site with pecking gestures.” Fidelity over the years is not easy with a twelve thousand mile journey each year. Between a third and a half of all nests contain a chick from another father.

The writer’s personality is stamped in his very opening words. “Some years ago I sat on the tarmac at Bole airport in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, talking to a soldier”. That says he has been around. (The ungainly “Ethiopia” is presumably an editorial insistence so the reader knows he is not talking about Addis Ababa, Arkansas.) He is amiably minded rather than scared of military men. The description continues lightly – “We had been chatting about not much for a little while” – an episode spoiled by the arrival of an officer of aggressive demeanour.

In his preparations for the journey, Clare reveals both his date of birth and its place of registration: Hammersmith. He touches on his part-Russian ancestry. There is a touch of self-mockery in his choice of hat – “Indiana Jones, naturally, purchased in St James, London, as was his.” The journey has a dramatic effect on Clare’s physique. In a Cameroon hotel he encounters the first mirror he has seen in days. His weight is down by a stone, he is sleeping better, but his digestion is unimpaired. Most dramatically the mirror presents a different face, one that “used to be rounded but is now triangular.” On a mini bus in Congo-Brazzaville his new form is no advantage. “With a skinny European ass [British “arse”] your only defence was to keep shifting the weight from buttock to buttock.”

Among writers A.A. Gill is Africa’s most frequent visitor and essayist. He makes complaint of the focus on miserabilism. Gill contends that life for many has an exuberance invisible in northern continents, a view confirmed to me twice by reports from Accra. The UN records that a third of Africa is now middle-class. Clare does not skirt around the background of blood – his continental crossing ends in Algeria – but nor does he wallow in misery.

Characteristically, he is seated on a bus next to a Touareg – his face “beautifully framed by his blue robes and turban”. He describes the courtesy of the relationship. “We never took a sip of anything without offering it to the other.” In Niamey he espies diplomats from the French embassy, generously “a credit to their country…glossy men and glamorous young women.” Clare himself is in a bar drinking with soldiers from a commando unit of the army of Niger.

In Cape Town he sees a “luminosity of light, which sharpens colours to the peak of their intensity.” On the ground he observes “Ferraris and Lamborghinis, jockeying for position in the freeway traffic.” The first Congolese he espies are in baseball caps and bright motorcycle jackets. For all Clare’s apprehension, moving from border to border, ironically the country where he runs into trouble is Spain. One of a cluster of Guardia Civil “grabbed me…threw me against the wall, pulled me back, turned me round and threw me against it again. He kicked my legs apart and spread-eagled my arms. There was a fierce, almost sexual excitement in him.”

Experience is shaped by expectation. Clare sees Europe differently on the approach from the south. I spent a weekend once in Naples but it was on a return from a half-formed Arabian Gulf city in a forty degree heat. Naples from that view was a model of civic sense and order, architectural elegance and moderate heat. Clare comes to France “a country I had thought I knew, but which in the light of what I had seen of its former empire I now saw afresh.” The arrival in Dover and the view through a window of south London are evoked with a fresh unpleased eye. The experience of the return to the normal is one common to all travellers “I struggled with hallucinations for weeks.” Travel, when it works, shakes personality. “I looked at the British as though as I had never seen them before.”

It helps if travel writers are good researchers, companions, conversationalists but in the end it is the words which count. Clare looks through the window of a bus in Nigeria. “The desert was made of light overlapping in unfinished rectangles: silver-yellow sand ran to a sky which leached into a sun too hot, too vast and too bright to look at. Shadows were small, dark, living things; everything else was still.” Travel writing is a crowded genre; six years on A Single Swallow looks set to last.

Read Carly Holmes in Conversation with Horatio Clare here.