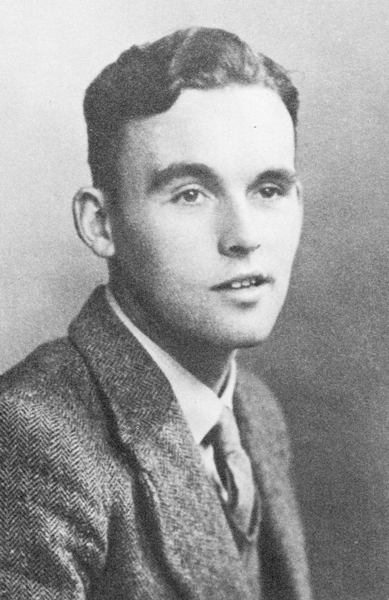

The writer Alun Lewis was born on this day 100 years ago.

Literary centenaries, like buses, often cluster in threes. Two Thomases and a Lewis in funerary quick succession. The centenary of R.S. was marked but in a sotte voce manner. That of DMT was an extravaganza of vapid Dylania more often than not only loosely connected with his writing. Alun Lewis has barely been acknowledged.

The number 9 bus from Cwmaman to Aberdare bore Alun Lewis from home to grammar and boarding school in Cowbridge (on a scholarship) to Aberystwyth and Manchester to continue his studies (also on scholarships). Lewis then went on military service to India and Burma.

M. Wynn Thomas offers the following biographical note: “Educated out of the working-class mining community of his native Cynon valley, he tried, during the depression, to use his socially ambivalent position to draw a middle-class readership’s attention to his people’s suffering. Hating the upper-class English officers with whom he was later sentenced to keep company in the army, he spurned protocol… such social dislocations were as nothing compared with his chronic psychological disorientation and the terrible gravitational pull of depression. Precarious stability came with marriage to Gweno, and socialist hopes for human advancement. Then came embarkation – and passage to India, where excess of ‘diverse and alien’ sensation bewildered him till he died”.

Lewis’ life ended, probably by his own hand, on 5 March 1944.

Lewis was 28 years old. A 28 year old soldier poet of the Second World War, younger than Dylan Thomas who died at 39 and much younger than R S Thomas at 87 but older than Keith Douglas at 24 (with whom he is often compared), Drummond Allison at 22 and Sidney Keyes at 21,his Second World War contemporaries. Alun Lewis is now barely remembered. Were it not for John Pikoulis and a small band of fellow travellers, of whom I am happy to be counted as one, his centenary would have passed largely unnoticed, as with so many before him. Is this a British thing? Why do so many of our cultural influences and informants lie ignored when we are so eager to puff up the yet-to-be-realised talents of others whose achievements are, as yet, far less substantial than those of Alun Lewis?

My interest in Alun’s work goes back to my rediscovery of Welsh Writing in English in preparation for postgraduate work at Swansea University. The gatekeeper was a certain Nigel Jenkins, the much missed writer and then Director of Creative Writing on the sea side of the ugly-lovely town. “What have you been reading recently?” was the opening question. I surprised myself with my roll call of the neglected heroes: Vernon Watkins, John Tripp, Idris Davies, Harri Webb and, of course, Alun Lewis, a shared favourite it turned out. Nigel was taken aback to find a fellow enthusiast and this formed the basis of our nascent friendship, cut short by his premature death.

The British disease has a Welsh variant. Not content with building up someone of promise and then taking every opportunity to knock them down in Wales, we have a penchant for even earlier demolition as a pre-emptive response. This lack of confidence serves us ill. We should be celebrating the achievements of our cultural vanguard. It is they who will inspire and sustain our youth, not the gym-bunnies in the WRU or the shiny suits in the Welsh Government or the heritage ‘industry’. What would “they” be doing to mark Alun’s Centenary I wondered?

Not much, it turns out, aside from Pikoulis et al, not much at all. Two events at Hay this year saw Gillian Clarke and Owen Sheers pay homage. John Pikoulis said: “These events are of great importance. Lewis was a very fine writer – probably the finest writer to have emerged from the Second World War. He was a man of great social conscience, with pacifist scruples. A great curtain of silence fell around talking about Lewis for years, but over the last 30 years or so people wanted to talk about him again.”

So why does Alun Lewis matter? Lewis wrote two small poetry collections and two short books of prose. They have stood the test of time when the work of other, wordier writers has and will not. Phil Carradice wrote that: “Many people consider the young Welsh poet and short story writer Alun Lewis… a far better writer than the more famous Dylan Thomas…it is difficult to make judgements about lasting quality. And literature should never be about competition, about one writer being better or worse than another. But Lewis’ story is certainly one of tragedy – it was a life cut short by a terrible and brutal war, a war that he hated and despised. Who knows what he might have achieved had the man been allowed a few more years of life and creativity”.

M. Wynn Thomas wrote of Lewis’ work that it is as “wistfully strong and evocative as those lonely wartime pill-boxes one sees stranded by time on coastal marshes, writing such as this, surely, is still worth our having, and holding – and cherishing?” Lewis announced his pacifism in a newspaper article: “If War Comes, Will I Fight?” In May 1939, he wrote “The army, the bloody, silly, ridiculous, red-faced army – in its bloody boring khaki – God save me from joining up. I shall go to the dogs like blazes – it’s the only honest way.” Only a few months later he wrote “I shall probably join up … I have a deep sort of fatalist feeling that I’ll go. Partly because I want to experience life in as many phases as I’m capable of … But I don’t know – I’m not going to kill. Be killed perhaps, instead.” It would appear that, despite a long history of depression, suicide was not on his mind at that time, but a sense of desolation is evident.

In his poem ‘The Sentry’ Lewis writes:

I have begun to die.

For now at last I know

that there is no escape

from night.

In one of his best regarded poems, ‘All Day It Has Rained’, Lewis describes the emptiness, boredom and futility of army life and his yearning for home and family:

All day it has rained, and we on the edge of the moors

Have sprawled in our bell-tents, moody and dull as boors,

Groundsheets and blankets spread on the muddy ground

And from the first grey wakening we have found

No refuge from the skirmishing fine rain

And the wind that made the canvas heave and flap

And the taut wet guy-ropes ravel out and snap.

All day the rain has glided, wave and mist and dream,

Drenching the gorse and heather, a gossamer stream

Too light to stir the acorns that suddenly

Snatched from their cups by the wild south-westerly

Pattered against the tent and our upturned dreaming faces…

Lewis intended to serve as an ordinary soldier in a Regiment unlikely to see frontline duty. Instead he became an officer in Burma, hardly a quiet posting and he again fell into depression. His wife, Gweno, wrote:

The effect on him was to plunge him to the depths of an unwarrantable despondency. The symptoms were always the same: the desperation on waking into the crazy machinery of an uncoordinated world – a state of mind he managed to get under control by the time he had washed and shaved and generally moved around; the lack of concentration and the feeling of utter failure and worthlessness. I don’t think others noticed anything wrong. If he appeared silent and withdrawn, wasn’t he, after all, the battalion poet?

This depression, Lewis’ “strange enemy”, his “cello of despair” he described as “my self-hatred”, “my living Mr Death”, “my Gestapo”. As an older man he wrote: “I can’t think without a cold sweat of the terrible anguish I lived in once, when I was 19, 20, 21”. To some extent this was a recurrent theme of his brief life. The contradiction continued when the erstwhile pacifist declined a posting as an instructor in intelligence matters, which would have relieved him of combat duties, in favour of active service. He wrote “I will not lecture until I have fought.” In his book, ‘The Green Tree’ (published posthumously), he wrote: “[The soldiers] seem to have some secret knowledge that I want and will never find out until I go into action with them and war really happens to them. I dread missing such a thing; it seems desertion to something more than either me or them… one of the instructors said to me, ‘You’re the most selfish man I’ve ever met, Lewis. You think the war exists for you to write books about it.’ I didn’t deny it, though it’s all wrong. I hadn’t the strength to explain what is instinctive and categorical in me, the need to experience. The writing is only a proof of the sincerity of the experience, that’s all.”

In his last letter to Gweno, Lewis wrote: “The long self-torture I’ve been through is resolving itself now into a discipline of the emotions and hopes of you and me … I feel my grasp is broader and steadier than it’s been for a long time. I hope it’s true, because that’s how I want to be and the rest of me is invulnerable. I want you to know that.” Lewis could have stayed safe at HQ but repeatedly requested to fight and his wish was eventually granted. On 5 March 1944 in Burma, in preparation for a patrol, Lewis’ loaded pistol was discharged. According to the official report of The South Wales Borderers it was an accident, more likely it was suicide.

As to the cause(s) we can only speculate. A return of earlier depression brought on by the imminent prospect of engagement with a cruel opponent? An inability to square the circle of love for wife, family and home with the attractions of an extra-marital affair in India? A fatalism borne of his intrigue with the ways of East Asia and the attractions of mysticism? In his poem ‘Karanje Village’ Lewis wrote :

And Love must wait, as the unknown yellow poppy

Whose lovely fragile petals are unfurled

Among the lizards in this wasted land.

And when my sweetheart calls me shall I tell her

That I am seeking less and less of world?

And will she understand?

Celebration has its place and a centenary is as good a reason as any. The arrival, under guard from New York, of the Dylan Thomas notebooks in Swansea to mark the centenary of his birth in 2014, to be met by the rapture of the masses as if they were the Holy Grail laid uneasily with me given that he had sold them when, as so often was the case, he was skint and had no further use for them. What price veneration? In stark contrast, I have had the great pleasure to handle the notebooks of Alun Lewis without white gloves and free of armoured glass and guards and to hold his school cap and ponder the thoughts that it once cradled. Alun Lewis’ poem, ‘Goodbye’, written for his wife after their last night together, stands as representative of his best work and is a fitting epitaph for a sadly neglected writer who deserves to be more widely read:

So we must say Goodbye, my darling,

And go, as lovers go, for ever;

Tonight remains, to pack and fix on labels

And make an end of lying down together.I put a final shilling in the gas,

And watch you slip your dress below your knees

And lie so still I hear your rustling comb

Modulate the autumn in the trees.And all the countless things I shall remember

Lay mummy-cloths of silence round my head;

I fill the carafe with a drink of water;

You say ‘We paid a guinea for this bed,’And then, ‘We’ll leave some gas, a little warmth

for the next resident, and these dry flowers,’

and turn your face away, afraid to speak

the big word, that Eternity is ours.Your kisses close my eyes and yet you stare

As though god struck a child with nameless fears;

Perhaps the water glitters and discloses

Time’s chalice and its limpid useless tears.Everything we renounce except ourselves;

Selfishness is the last of all to go;

Our sighs are exhalations of the earth,

Our footprints leave a track across the snow.We made the universe to be our home,

Our nostrils took the wind to be our breath,

Our hearts are massive towers of delight,

We stride across the seven seas of death.Yet when all’s done you’ll keep the emerald

I placed upon your finger in the street;

And I will keep the patches that you sewed

On my old battledress tonight, my sweet.

Alun Lewis dead at 28. Dead, but not forgotten.

Happy 100th birthday, Alun.

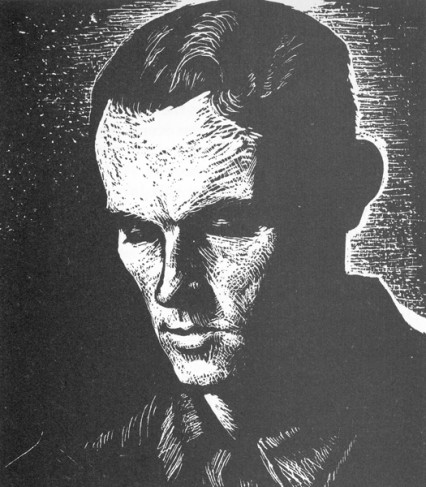

(Images courtesy of Seren Books)