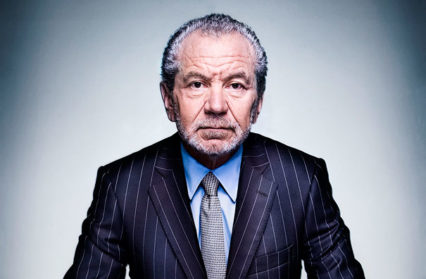

In the month where broadcaster and Culture Secretary make a kind of peace, Adam Somerset reads Alan Sugar’s Unscripted, a book that starts with scepticism and ends with unqualified admiration for the BBC.

Alan Sugar’s autobiography What You See is What You Get (2010) was reviewed in all the broadsheets. Literary editors have collectively passed on Unscripted, Sugar’s chirpy account of his unlikely transition to reality television presenter. In this it reflects the author’s own experience with television executives. The Apprentice is a hit, year on year, and it picks up BAFTAs en route. When its star presenter peppers the decision-makers with ideas for new formats no-one wants to know.

The autobiography of 2010 is well worth reading. There are insights into the creativity of manufacturing. The then plain Alan solves the problem of a hi-fi turntable lid by studying the moulded plastic of a butter dish. He is frank on the demise of Europe’s largest independent computer manufacturer. When faced with a catastrophic quality failure from a supplier the Sugar company simply lacked the engineering depth to address it. Sugar is revealing too on personal qualities. He muses on the low level of personal empathy. In fact it is essential. Intensity of focus to the task is what makes any enterprise take wings. Unscripted is a lesser book, not really recommended, but has interesting insights into the television industry.

The first is its fissile nature and maze-like structure. A consumer electronics business is complex but the route of suppliers to manufacturer to retailers has a crystalline simplicity when compared with media structures. The book’s tone is pure Sugar. If it has been ghosted it is colloquially close to the source. The author takes pains to describe the complexity of rights-holder versus production and commissioning companies.

This has a comic side. When The Apprentice is sold overseas everything changes. The share that Sugar takes to be his undergoes a massive dilution due to a whole new raft of commissions and other payments. Equally naturally the television bosses cannot understand the protestations when it is just the way their industry is.

There is an equally comic beginning to it all. This is a CEO who on occasion has Downing Street on the telephone line. He finds that in the jargon of his new industry he is “the talent.” That does not stop the creatives jumping on the private jet for meetings at the talent’s Mediterranean home. But when the BAFTAs come about, Sugar is put out that the glory is all for the producers. Those are the rules. The talent is decoration. In response, Sugar gives a trusted long-term employee in his own organisation the task of sourcing and making a line of his own replica statuettes. It is naturally achieved for a lower cost and he quotes a better price to the BAFTA organisers.

On aspects of The Apprentice itself he is at times too close. He asserts more than once that it is a serious business programme. It is not, although it is a rigorous selection process. A business is formed of human, physical, financial and intellectual resources. The candidates have to charge about, instead of economically checking information on their phones, because television needs action. The author mentions that a rented house in Sheen for the candidates means horrendous traffic times in those big black SUVs. In the land that is not television they would nip to the station twelve minutes from Waterloo. But television is unrelenting. One revealing aspect is the cruelty of the conditions that it imposes on its would-be winners. Long periods of isolation from friends and family are exactly the opposite of what nurtures effective work performance.

Like any endeavour there are plans but our world is half-made of sheer serendipity. The Apprentice took off in part because of the trio in the boardroom. One was a serious-minded senior City lawyer, another a PR executive near the close of a career. The chemistry of the trio was entirely unexpected and brilliant.

Unscripted looks to the fates of the winners. The candidates on their hundred thousand a year were difficult to fit into the organisation. Sugar is not particularly charitable towards his own Viglen chief executive. Long-standing employees on their thirty or forty thousand a year looked sceptically at these newcomers of scant experience. The scheme worked best when the winners were given blue-sky projects. Sugar is obviously proud of The Apprentice in its second format. The quarter of a million pound business partner idea was, he says, his own idea to fit a post-2008 Britain. The winners and their ideas have all flourished.

Sugar is the most public of enterprise figures. His own business is the exact opposite of the version of enterprise on the screen. Long-term loyalty of employees and stability are the necessary counterweight to environmental turbulence. In the tech world the Bergs at the social media colossus – Zucker and Sand – preside over a company that is as managerially stable as the Tweeters are volatile and disordered.

Sugar starts his decade in television bewildered by its ways. He was “a person, who came into television thinking they were a load of plonkers.” He cites early on a staggering piece of organisational slipshodness. As The Apprentice succeeds the BBC high and mighty emerge to be his friend – and appear at ceremonies. His last page comprises four paragraphs of unstinting and unqualified admiration for the BBC.

Are we better off with The Apprentice? Probably, yes. It has made contestants like Tim Campbell and Saira Khan valuable role models. It is a meritocracy. If Sugar has thrown out the blue-bloods and the plummy-voiced with regularity it has rewarded a Cambridge graduate, Simon Ambrose, where appropriate. Sugar recognised the value in Tom Pellereau, described as “a slightly eccentric inventor-type boffin.” If the format is necessarily win-lose the book makes mention of several contestants still in contact with Sugar or Hewer. Of one forceful but excessively voluble candidate the book reports that, after his time of media fame, he has returned to his home town, married his girlfriend of old, and resumed his old job of sales manager for a local printing company.