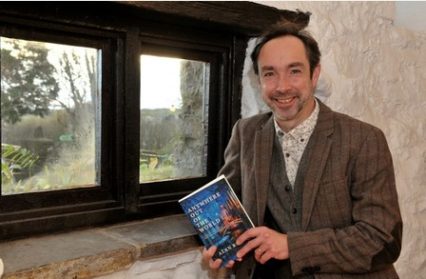

There is nothing in Alan Bilton’s appearance to betray the surreal landscape of his imagination. Tweed-jacketed and with a jaunty bounce to his step, he is the very image of the British academic. In addition to several scholarly books on American culture and silent film, Bilton is the author of two novels: The Sleepwalkers Ball which was described as a cross between Kafka and Mary Poppins and The Known and Unknown Sea, tragi-comedy inspired by the silent film A Trip to the Moon.

His latest publication is a collection of short stories, entitled Anywhere out of the World. The reference to Baudelaire’s poem is apt, for these are stories of pure escapism, bursting through the boundaries of realism into the realms of the absurd. There are paintings that become portals, a taxidermist specialising in fleas, a hotel with floors in different time zones and a talking cauliflower. The collection has drawn comparisons to both Psycho and Monty Python.

In person, Bilton is charming and self-deprecating, quick to laugh and always ready with a witty one liner. We settle down for a coffee in Brynmill Coffee House, where we are offered freshly baked pastries. I cannot resist quoting from Anywhere out of the World – “Madame your pain aux raisins are so flaky…” It’s a line that might have strolled out of the eighties sit-com, ‘Allo ‘Allo, along with Bilton’s description of Madame Lacarrié, who “filled the café from floor to ceiling, her red hair creating the impression of a burning building, black eyes still smouldering.”

There are some wonderfully weird characters in Anywhere out of the World. Would it be fair to say that many of them are larger than life?

Yes, they’re cartoonish – they’re there to do one thing. Characters don’t always need to have depth, or a back-story or a history. One, quickly drawn sketch – if it works – can be a lovely thing. But as soon as you’re not realistic, people do get upset by it. It’s either the intellectual argument; oh it must mean something else, or they think you should be creating realistic well-rounded characters and you’re not. Fiction can be more than one thing; there are many more possibilities than just realism and the idea of limiting yourself to observing the every day life around you is very restrictive. For me, twenty-first century every day life doesn’t seem a very rich source of inspiration. All my instincts as a writer go against that. Hemingway said ‘it’s the writer’s job to tell the truth’ but I’ve always felt the opposite; I think it’s the writer’s job to make stuff up. What you make up is generally more fun than the truth. I’m no fan of the truth!

I studied A-level art at sixth-form college, and I remember we were asked to draw a red pepper as a still life. It was very exotic; I’d never seen one before – this was Yorkshire in the eighties. There were all these shapes in it so I drew funny little whorls, as if it were a spaceship or something, and I painted it a different colour. I got an N! I still feel the injustice now because I felt that what I’d drawn was better than the real thing. Otherwise, it was just a vegetable.

The scar of that red pepper is obviously still with you – I notice that it makes a reappearance in Anywhere Out of the World as one of Ferrand’s paintings! How do you respond to criticism these days?

The more distinctive and quirky a book is, the more likely that some people will really like it and others won’t get it at all. If somebody doesn’t get it, that doesn’t hurt. If it’s not their thing, that’s okay. If someone said, I like that type of thing but yours is terrible then that would hurt.

You say that you’re not a fan of the truth. What is it then, that drives your work?

The purpose of my work is the pleasure of making something. All my books are about giving pleasure – entertaining. I’m interested in crafting a specific world, a specific mood that allows various other ideas to be played out. On an emotional level, I don’t think they’re very difficult books, I think they’re very straight forward… they don’t require a huge amount of intellectual knowledge. I’m not creating a crossword to be solved; it’s a mood to be enjoyed.

Your writing style is vibrant, playful and very distinctive. One of the things I most enjoy, is your talent for similes – phrases like, “The rings on her fingers clicked like castanets.” How does that playfulness with language inform your writing process?

I work to the opposite of the creative writing maxim, ‘kill your darlings.’ I keep all my darlings very safe and I look after them. I build my story around my darlings. Often, the idea comes as I write the words on the page. The words fall into a certain position – if it makes me smile, if it’s striking or beautiful, then it stands. Meaning is secondary to the immediacy of the words.

Many of your stories feature mysterious mists, looming shadows, unseen creatures that flit past the corner of the eye. Are there elements of your own childhood imagination in the worlds that you create?

Yes, I’m not that different now to how I was as a kid, with my papers and felt tips spread out on the table. Kids are quite happy drawing stick figures and square houses and strange black skies and what I’m doing is not that different really.

For kids, what might have happened is just as important as what did happen, what they want to have happened, or what they’re scared might happen. I think that’s a very rich source of inspiration for a writer.

‘The Honeymoon Suite’ for example, was the easiest of the stories to write. I wrote it really quickly; it just rolled playfully along. I didn’t think of the ending; obviously, I thought the lines would converge but in the end, there are two different endings. Stories don’t have to follow a straight line; it can be a crooked line. You can have characters in different spaces, a dream-like logic in which both these things are equally true. So long as you can hold those contradictions in your head at the same time – and I think kids can – it gives a story that extra spark.

Have you always written stories?

I went to a tiny school – only thirty of us in the whole school. If you wrote stories you were allowed to keep going. You didn’t have to do the next lesson if it was something boring like maths. So when I was eight or nine, my stories began to get longer and longer – some were sixty odd pages!

I was the only one who passed the eleven plus. I went to grammar school and I hated it. I’d been a big fish in a small pool and suddenly I found I was no good at anything. The only thing I was any good at was writing. One of the first stories I wrote there was returned to me as a ‘fail’ because the teacher claimed I must have copied it from somewhere else – I hadn’t! All the imagination was stamped out of us. You had to conform. That beat me down for a bit.

I didn’t write again until university. University was a big eye opener. I’d never been to an art gallery before I went to university. I joined the film society and suddenly I was watching French New Wave – all this arty stuff. It changed the possibilities for me. I’m a big film buff – geeky. I like really odd 60’s and 70’s, arty dream films but I’m in the minority. Films that have no logic except dream logic are fairly hard going. In little doses, surrealism’s great, but it’s a bit like tickling; it’s fun when it starts but after a while, it ain’t funny anymore.

What are you working on at the moment?

Short stories bring out all your natural inclinations in a very intense way. I think you show your cards in a collection of short stories. It’s a hundred percent you.

I can’t write people being lost in cities searching for dogs endlessly… the next book is set in the Russian civil war and starts with a murder. It’s got several strong narrative elements – a mystery that you want to solve. There are soldiers, a shoot out, all this stuff that’s not naturally me at all. I have to see now whether I can use that and yet still bring in the oddness, still do interesting things with it.