As part of Wales Arts Review’s coverage of the new WNO season, Steph Power spoke with David Pountney about Alban Berg’s Lulu, which opens tonight at the Millennium Centre, Cardiff. It is a significant first staging of the complete, three-act work in Wales. There are further Cardiff performances on February 16th and 23rd and the production will tour to Birmingham, Llandudno, Southampton, Milton Keynes and Plymouth.

David Pountney is an opera director and producer of international distinction and was appointed Chief Executive and Artistic Director of Welsh National Opera in September 2011. He won renown for his pioneering Janáček cycle in collaboration with Welsh National Opera as Director of Production for Scottish Opera (1975-80) and his subsequent staging of over twenty operas including Rusalka, Osud, The Midsummer Marriage, Doctor Faust and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk for English National Opera, where he became Director of Productions in 1980. He has directed over ten world premières, including three by Sir Peter Maxwell Davies for which he also wrote the libretto, and has translated many operas into English from Russian, Czech, German and Italian. As a freelance Director from 1992 he has worked regularly in Zürich, at the Vienna State Opera, at the Bayerische Staatsoper Munich as well as opera houses in America and Japan, and in the UK has a long-standing association with Opera North. He has won numerous international awards and is a CBE and a Chevalier in the French Ordre des Arts et Lettres.

Steph Power: David, Lulu is your first new production for Welsh National Opera as Artistic Director. I was wondering what attracted you to the piece?

David Pountney: Well Lulu (Alban Berg) is one of the great masterpieces of twentieth century opera. First of all, it’s a fantastic play and a fantastic concept of a central character – which comes from Wedekind, obviously. Berg is one of the leading thinkers about opera of the twentieth century, so it’s amazing to have that combination with the invention of a really strikingly individual character. Actually, there are not many stories in the world – didn’t somebody say there are only seven basic plots?

Steph Power: Yes – the bases for myths.

David Pountney: But you know Lulu comes close to being the invention of a new character – although she obviously has very clear connections with Carmen and Don Giovanni; they’re all trying to do the same thing in a way. But no, it’s fascinating to have that combination of Berg’s re-thinking about musical language and his espousal of what was then very revolutionary dramatic ideas of Wedekind. So it’s a very exciting piece to do. Fun actually, a lot of fun.

SP: Where do you feel that Lulu sits on that continuum between, say, post-Romantic tragedy, black comedy and quite serious social critique?

DP: There is quite a lot of black comedy in the piece and I would say that it observes society in quite a cynical way, but without necessarily being a critique of it; at least, it doesn’t wear its heart on its sleeve and there’s not much attempt to make you feel sorry for Lulu. Lulu is at the same time a victim and a perpetrator and that’s one of the interesting things about combining this opera with The Cunning Little Vixen this season. Because the vixen herself, like any predatory animal, is potentially a victim – of us, for example – and also a predator of all kinds of other, less powerful creatures. And Lulu inhabits very much the same kind of world.

SP: I quite often see Lulu as a mirror for those characters around her. I don’t know if you agree with that? It’s as if she’s a huge character, and yet she’s not a character in her own right.

DP: I think that’s absolutely correct, yes. To me she’s a spirit. The first play of Wedekind’s is called Earth Spirit and Lulu is not really a person – and that’s made clear in a way by the fact that nobody’s quite sure what her name is and nobody knows where she came from. There’s a lot of discussion about who her father might be.

SP: Whether he’s Schigolch?

DP: Yes, exactly. So she’s a mythic being really and I’ve made that quite clear in the production. And, as you absolutely rightly say, you learn what she is by watching everybody else go crazy around her. So I’m deliberately adopting a strategy in the production of not making her too extravagant. Sometimes people play Lulu by throwing their legs around and taking their clothes off; that, to my mind, is not what erotic power is – it’s much more to do with suggestion. Just simply the magnetism of somebody walking into the room and everybody thinking ‘I want to sleep with that person’. There are people who have that without flaunting it or doing anything or being overt about it.

SP: In terms of the piece as a dramatic whole, it’s quite notorious really for being paradoxical, in that the dialogue, the plot and the intensely emotional music are quite often juxtaposed.

DP: Well, Wedekind was deliberately protesting against the kind of bourgeois drama where everybody takes themselves terribly seriously.

SP: The whole naturalist, realist movement?

DP: Yes – and I think you can sense that. I think what really destroyed that – and the entire pretension of taking almost anything seriously – was the First World War, which was a gigantic catastrophe. All those things like patriotism and religion and politics – all those ground bases of society up to that point – were shown themselves to be involved in the First World War in a totally disgusting way. That created such a tide of reaction, and one of the things that reaction produced was Dada. The point about Dada is that it sees everything as absurd; and so Dada took everything that people had taken seriously – like religion and politics and belief in your country and morals – and revealed them to be, in a certain sense and in certain circumstances, absurd. Wedekind very much picks up on that idea – so that’s why you have in Lulu that amazing gallery of absurd figures.

SP: – The ‘freaks’.

DP: Freaks, caricatures. Because he’s saying it doesn’t matter who you are – a bit like Leporello’s catalogue. It doesn’t matter whether you’re thin, fat, tall or rich, poor, ugly, beautiful – Lulu’s erotic power possesses all those people equally. And that destroys the whole edifice of importance or class or respect; all those orders of society are completely subverted by this power which treats them all with equal indifference. I suppose, in that sense, Lulu has the same function as the famous play by Schnitzler, La Ronde, where, in a group of people, the prostitute sleeps with the soldier, the soldier sleeps with the countess, the countess sleeps with the farmer, the farmer sleeps with the tax collector, the tax collector sleeps with the prostitute and so on. By the end, everybody’s slept with everybody else by a distance of one or two or whatever. And it’s that same kind of feeling with Lulu; a levelling of all these things that have separated everybody into a kind of hierarchy.

SP: And so, pulling apart the social hypocrisy.

DP: Yes exactly. But, alongside that, there’s also another reason for the consistent element of humour, clowning, circus and cabaret; this world of popular entertainment is important in Lulu, partly because of that idea of not taking anything too seriously. Though it has to be said, the music takes itself very seriously!

SP: It does!

DP: And that’s another story in a way! But, picking up on the Dadaist tendency, that is something that’s reflected right across the art of that period. If one thinks of all those paintings of harlequins and circuses – of all those Picasso circus paintings and of Max Beckmann – and all the people who were fascinated, in that period, by popular art. That was very much a move away from seriousness, or pretentious seriousness.

SP: The whole idea of the pierrot figure is present in Lulu with her portrait – which, in the score is described by Berg as a portrait of her dressed as a pierrot. Do you incorporate the portrait into your production?

DP: I’ve done the portrait in quite a different sort of way. First of all, it’s a sculpture and, secondly, it’s based on – or really is a copy of – the work of a very eccentric artist called Hans Bellmer. Bellmer made all kinds of constructions of nearly always female limbs, so that he objectified the body, if you like, in a very provocative way. Because, again, he’s saying: these are just limbs. The whole idea of the portrait or the nude has been the embodiment of a sort of beauty; of nature, or the goddess within man, or whatever. But Bellmer deliberately subverts all that – also in a kind of Dadaist, rather absurdist way – by producing these kind of assemblies of parts; actually, he started out by working with doll parts and there’s a whole series called Bellmer’s Dolls. So he very neatly captures that feeling of an absurdist vision mixed with an element of perversion – which is undoubtedly also lurking there in the Lulu story. I mean, part of the Lulu story is a story about a young woman who’s been groomed for underage sex – which, of course, strikes a very powerful chord with us today.

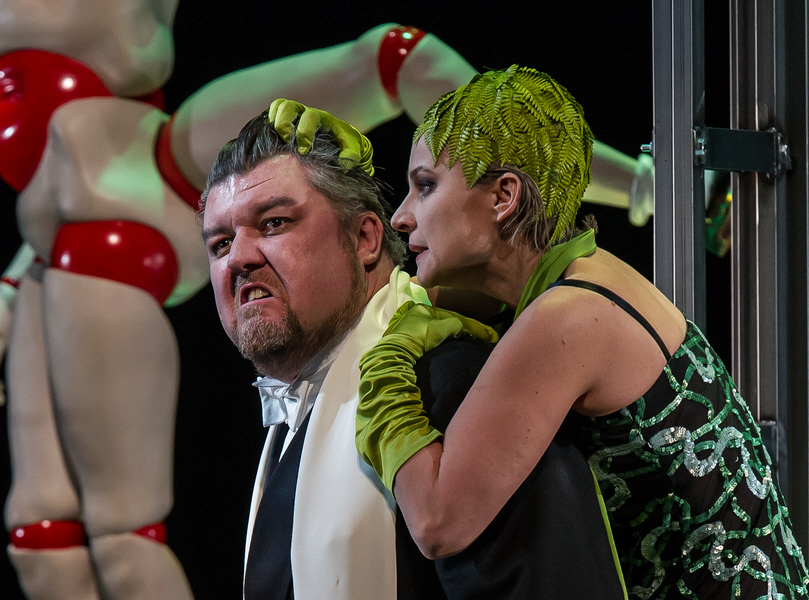

and Ashley Holland (Dr Schon)

Photo: Clive Barda

SP: Yes, very much so – and which goes right back to the questioning of sexuality and identity that happened across fin de siècle Vienna, running right through to the Anschluss really.

DP: Yes, absolutely.

SP: In terms of Lulu as a second opera, do you see it as having moved on, as it were, in dramatic vision from Wozzeck – which, in some respects, is a much more straightforward depiction of someone who’s a victim of circumstance?

DP: Strictly in terms of pure operatic achievement on a very high level, Lulu is a decline from Wozzeck – and there’s a very simple reason for that. The author of the Wozzeck play, Georg Büchner – who lived a great many years earlier – was an incredibly revolutionary writer. He devised a completely new way of structuring a play, with very short scenes making a kind of collage that add up to a story. And he constructed these short scenes out of amazingly economical, pithy sentences. This was the most perfect opera libretto that you could ever imagine, as one of the things that you most want from a libretto is for it to be concise – because music always multiplies the length of time it takes to say any sentence by four! So the Büchner was an amazing libretto, both in terms of its concision and in terms of its scenic structure, which allowed Berg to create a kind of string of pearls; short moments which absolutely define the progress of the story. But when he came to Wedekind, he was facing somebody who had really no structure at all.

SP: Very sprawling actually.

DP: Yes, Wedekind wrote two incredibly sprawling plays that are pretty much unperformable even today as they stand, in that everybody has to cut them in some way. And, you know, Berg did cut a great deal of the plays. But I think actually, in order to have achieved another opera as compelling as Wozzeck, he would have needed to cut another third of the text. And that’s one of the reasons why he didn’t finish Lulu. It’s tragic really. I always say that if he could have got on a train and taken a short trip to Brno and gone to Janáček and said, ‘excuse me Leoš, how would you cut this play’, Janáček would have got his pen out and gone like this [makes large crossing-out motions].

SP: Yes I can imagine that!

DP: Then you’d end up with a few little lovely sentences here and there! You know, Berg was much too in awe of Wedekind, and too respectful of him. So, with each scene you think, ‘there are five sentences unnecessary in this scene’.

Of course, having said that, we are talking on a very high level and it’s still a fantastic piece. But it just doesn’t get to the very hard to reach level of absolute perfection that Wozzeck arrives at. Nonetheless, it is a fantastic experience to do and to watch and to listen to.

SP: Somehow I think its flaws make it compelling in a way – that sense of wondering what Berg was striving for, which is so fascinating.

DP: Well, Wedekind did create this character who is, in the last analysis, absolutely unknowable. Whereas in Wozzeck, you end up being very clear about who’s the victim and who’s the perpetrator and about what’s gone wrong. Lulu is deeply ambiguous because it’s examining an aspect that is within all of us and which we all suppress – which we need to suppress because otherwise we’d all destroy each other! Hopefully, each of us finds one or two moments in our life when we can let that out; run rampage for a bit. But you couldn’t go on like that for very long.

SP: No, society would fall apart!

DP: Yes!

SP: Coming back to the idea of cuts, I understand that you’ve chosen to use Eberhard Kloke’s new completion of the Third Act. Could you say something about that? What led you not to use the Cerha?

DP: Well you know the Cerha is, from a scholastic point of view, utterly worthy, and done with indefatigable attention to detail. Cerha probably got as close as it was possible to get to exactly what appeared to be the case regarding the state in which Berg left the score when he died. But, particularly with a piece as dense and as complicated as Lulu, none of us can really know what Berg might have done had he gone on to revise it. And he did say himself that he needed to start again from the beginning and revise the whole piece – he was aware himself that it wasn’t perfect.

I think the fact is that the Paris scene – which is the main difference in Kloke’s revision – is, in its full-blown Cerha version, something which completely defeats the audience’s energy and ability to concentrate, and so to sustain their interest through to the magnificent final scene – which is one of the great scenes of all opera. So I think the Paris scene as Kloke has it is considerably shorter – or, at least, it opens options to making cuts, which we enthusiastically embraced! It’s just much more transparent and fluid and fast-moving and gets us through what is a kind of cabaret scene in itself, without overburdening that scene with too much detail and too much portentous significance so that we’re all ready – I think the final scene will make a much greater impact on the audience because they’re not being inundated with density and complexity beforehand. So I hope that it will really work in a positive way. I mean, nobody can say necessarily ‘yes, Mr Kloke’s version is much better as a scholar of Berg than Mr Cerha’s version’ but I’m not really bothered either way about that argument – I’m bothered about what makes it a good evening for the audience.

SP: In terms of another aspect of where Lulu sits within early Twentieth Century opera, there’s recently been growing interest in composers like Franz Schreker and Zemlinsky and Korngold. Do you think that that interest, and the growing awareness of their work, opens up an avenue for reassessment of where an opera like Lulu might sit within that?

DP: Well I suppose to some extent, the survival of certain masterpieces in each generation means that you lose the context in which they were created. Most of the time, that’s a pretty good thing because there are a certain number of first-class operas and a certain number of second-class operas – and you don’t really want to be bothered with the third-class operas! The second-class operas can often be extremely interesting. But always, you’re left with these tips of the iceberg that survive down into history and you don’t know – and probably don’t want to know – about all the stuff that’s sunk.

But there was a particularly artificial reason why we got cut off from the early twentieth century pieces – which was a staggeringly creative period. I mean, people tend to think the 19th Century with Verdi and Wagner was the great period but, if one looks at what was written in the twenties and thirties, it’s absolutely amazing what an inspirational outburst of creativity there was, centred mainly in Germany of course. And what really happened was that, first of all, the Nazis banned them all – which, in a way, wouldn’t in itself have mattered very much since the Nazis didn’t last very long. But then, in reaction to the Second World War, the whole modernist element of musical taste banned them again! So all the post-Romantic or late-Romantic composers first of all had to suffer Hitler – and then they had to suffer Boulez! – There was a very damaging kind of hard-line view. And one only has to look at what happened to Goldschmidt at the BBC; he’d written one or two really splendid operas but he was relentlessly ignored by the BBC because it thought we didn’t want to go back into that late-Romantic quagmire, out of which people claimed – I think quite wrongly and unfairly – that the whole poison of Nazism had arisen.

So in a way those composers suffered doubly and so, yes, there is a good case for re-evaluating those pieces – and Lulu – within the whole period.

SP: Thank you very much for your time David. I’m really looking forward to Lulu and to continuing our discussion with The Cunning Little Vixen.

and Natascha Petrinsky (Countess Geschwitz)

Photo: Clive Barda

Banner illustration of David Pountney by Dean Lewis

Recommended for you:

David Pountney spoke with Steph Power about the strikingly complementary sensibilities of Musorgsky and Janáček – and much more.