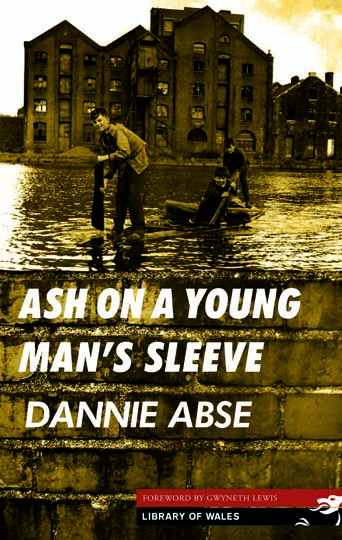

Jon Gower reviews Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve by Dannie Abse, a semi-autobiographical account of the Holocaust and the loss of innocence.

If ever there were summer days with long, long shadows they were those of 1930s, when to live in Wales was to sense the far off dramas being played out as the Holocaust began its evil, as Hitler started his demonic rise, even as a myriad tragedies, personal and familial were enacted in the starving terraces of south Wales and elsewhere as the Great Depression strip-mined hope itself. It was a decade of other changes, too, not least technological…

Suddenly, some anonymous futuristic man, a long way away in a power house, touched some gigantic switch and the lamp-posts jerked to life; and, though it was not dark, the electricity demarcated the country from the town more absolutely than any fumbling sunshine of a windy summer afternoon.

Yet there is sunshine enough in this, Dannie Abse’s tender autobiographical fiction – the characters in Ash On a Young Man’s Sleeve closely resemble Abse’s own family, but there are some which are entirely made up – oh and a corrective, when I say sunshine, well, that only appears when the gauze of insistent Welsh drizzle lifts off the land. Then the blackbirds whistle and ‘Butterflies, boozed and drugged with August’ crookedly flutter through the air.

Taking its title from a line in T.S.Eliot’s ‘Little Gidding’, the book is couched in a near-confessional tone, set by some words early on: ‘Cariad, clean heart, listen to me, this is my beginning. Let me start again.’

The fulcrum of the book is the friendship between two young lads, Dannie and Keith. Dannie, the character’s family, complete with brothers Leo and Wilfred, is, to all intents and purposes, the same as Dannie the author’s family, so one could conceivably cross-refer between this fictionalized version of his life and A Poet in the Family, being Abse’s autobiography.

One of the book’s many delights are the rapid-fire, staccato exchanges between the two lads:

‘I like Barry best,’ said Keith.

‘I like Ogmore best,’ I said.

‘I like Porthcawl best,’ said Keith.

‘I like Cold Knap best,’ I said.

‘I like Lavernock best,’ said Keith.

‘I like Penarth best,’ I said.

‘I like Southerndown best,’ Keith said.

‘I like Barry best,’ Keith said.

‘Fight you for it,’ I said.

But we didn’t. Keith put his head out of the window and I said, ‘Dogs do that,’ so he pulled his head back in again.

Such exchanges, such machine gun volleys of badinage are plentiful and there is much delight to be had in these daft but engaging trumping games. They are funny calls and responses, giving the story an authentic ring of gawky adolescence.

‘How old’s your mother?’

‘Thirty.’

‘Mine’s forty.’

‘Mine’s fifty.

‘Mine’s sixty-three.’

‘Mine’s ninety.’

‘Mine’s hundred and ninety.’

As a poet’s novel there are, of course, quiet drifts of beautifully written passages, scudding like high cirrus clouds over Abse’s blue remembered hills, or, rather, the mushroom-abundant Rhiwbina hills of his childhood. But the novel is economical in its doling out of beauty. The sea at Porthcawl comes over the promenade with ‘sloppy white paws.’ The autumn weather is ‘smoky beer-coloured.’ The Rhondda valley is ‘naked, bony, the green dress pulled off it.’ Abse brightens his prose with pointillist little dabs.

Because even as Dannie and Keith enjoy a camping holiday at Ogmore, where Keith falls under the spell of an older woman, Henrietta Gregory, on mainland Europe the shadows gather and darken. It is a sign of Abse’s maturity and confidence as a writer – Ash On a Young Man’s Sleeve was written when he was still a medical student – that he can change register seamlessly, interlacing cozy Welsh reminiscence with some very nasty noises off.

So we have the stand-alone story of Grynszpan, a ragamuffin Jewish assassin out to kill a German diplomat. Or find, among the seaside adventure of the young lads, a survey of what else is going on in the world in 1934, from Mussolini strutting through the Piazza Esedra to Oswald Mosley suggesting that the English are being ‘throttled and strangled by the greasy fingers of alien financiers,’ by which he undoubtedly means Jewish bankers.

The book ends as bombs drop on Cardiff, and with a death. It heralds the end of summer, or summers, and the death of innocence – and of an innocent, Keith. Ash On a Young Man’s Sleeve concludes with a lovely meditation on falling leaves, thus concluding, with a gentle music, a spare and affecting book, full of limpid prose, shaped by a doctor-in-the-making, who is here just beginning to hone and wield his writer’s finest scalpel, to lay bare life.

You might also like…

At Hay 2012, 89-year-old Dannie Abse CBE discusses his autobiography Goodbye Twentieth Century, which deals with survivor’s guilt and the changes the world has undergone.

Jon Gower is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.