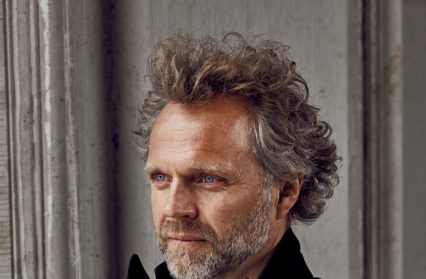

Steph Power reviews Danish conductor Thomas Søndergård’s inaugural concert with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales.

The appointment of a new Principal Conductor to a major orchestra is a big event with far-reaching ramifications for the musicians concerned and their audience; a fact hardly lost on Danish conductor Thomas Søndergård, to whom the baton was officially passed, as it were, on October 12th from Thierry Fischer, outgoing Principal at the BBC National Orchestra of Wales. Søndergård’s choice of repertoire for this inaugural concert revealed aspirations for his four-year tenure on both personal and orchestral levels. But it was the opening piece that threw down the gauntlet in more than one regard.

EXPO, a short, flamboyant showcase of orchestral virtuosity by Finn Magnus Lindberg, was commissioned in 2009 to celebrate the inauguration of another, similarly youthful conductor at another orchestra; Alan Gilbert at the New York Philharmonic. It’s inclusion here drew bold comparison between that event and tonight’s concert in Cardiff – perhaps overly bold, given that a bright start gave way to workmanlike performances in key ensuing items. However, the piece also signaled Søndergård’s welcome intent to perform not only works by fellow Scandinavians, but contemporary music alongside older, more familiar repertoire. EXPO fulfilled both criteria and was used here to play a fun, if somewhat unsubtle, national card as a link with Jean Sibelius’s Symphony No. 5 in the second half; a piece nonetheless worlds away in tone and seriousness of intent, and the most ambitious item on tonight’s programme.

But before that came less challenging fare from Edvard Grieg and Richard Strauss; firstly, in a series of orchestral songs also designed to please followers (at least, those with long memories) of the Cardiff Singer of the World competition, won in 1993 by tonight’s Danish soloist, soprano Inger Dam-Jensen. Grieg was, of course, also a Scandinavian composer and the first to achieve wider fame outside his native Norway – although his music is still snubbed by some who persist in the condescending belief that only proven symphonists can earn the right to ‘major composer’ status. Where Grieg excelled was as a miniaturist and writer of deceptively simple songs (he, like Strauss, was married to a soprano), and the set of four on offer tonight were delivered with grace and sensitivity; the first, To Brune Øjne Op. 5 No.1, delicately orchestrated by Barry-based composer Christopher Painter. A more full-bloodied, dramatic approach from soloist and orchestra alike would have enlivened the three Strauss songs which followed; these were somewhat fey and underwhelming, but nicely wrought for all that, with Dam-Jensen and orchestra finding comfortable rapport.

Strauss, too, had musical detractors and initially had difficulty earning respect as a composer, but for wholly different reasons; in his case, an advanced and, to some, shocking chromaticism begot a reputation as an enfant terrible. With the tone poem Till Eulenspiegel – his fifth in a genre he developed with extravagant artistry – he stuck out his tongue at critics who could not, after all, ignore its dazzling feats of invention, wit and colour. How far Søndergård himself may or may not identify with the anti-hero prankster of the folk tale from which the piece springs is open to question (notwithstanding his cheeky-chappy exhortation to the audience’s ‘beautiful faces’ to stay for a post-concert interview). But tonight’s performance could certainly have been more rudely characterful. This is not a piece with which to tread carefully and, although the orchestra clearly enjoyed themselves once warmed up – the Strauss eventually picking up where Lindberg’s virtuosic energy left off – it needed a more insolent relish.

It was, in part, interpretation of another tone poem which brought Søndergård critical acclaim upon his BBCNOW debut in 2009; then with Sibelius’s En Saga. Tonight, he upped the ante considerably in tackling the Finn’s profound and problematic Symphony No. 5. It is not the harmonic or rhythmic language Sibelius employs that makes this and other of his key works so difficult to bring off, nor any specific aspect of instrumentation or technique; indeed, at the time Sibelius wrote and then revised the 5th Symphony during and after World War I, his tonal idiom appeared, on the surface, positively backward-sounding beside the atonal experiments of Central European contemporaries. However, this and other of his major scores have often baffled those who seek in vain therein for conformity to prevailing Austro-German symphonic models. Furthermore, Sibelius is not simply a proto-Romantic, inspired by national identity and lonely Northern wilderness (although this can also be true), but his organic formal and harmonic processes are so subtly radical as to constitute a unique, modernist development in themselves. It is nonsense, therefore, and not just simplistic to assume that a Scandinavian must be able to perform Sibelius convincingly just because he or she is Scandinavian, for this ignores the extent to which Sibelius’s unique sound springs from purely musical procedures rather than nationalist sentiment.

Søndergård’s interpretation on this occasion showed a great deal of promise but was far from polished or convincing overall; much of the formal expansion and contraction of the first movement, for instance, was marred by a feeling of its being bolted together – both in terms of the movement’s span and the instrumental sections, as woodwind, brass and strings sounded at times completely disparate rather than fragments of one voice, now emerging from, now dissolving into the disquieting orchestral texture. Such waves occur throughout the work, in which the three movements are themselves different stages within one, extraordinary whole. But, despite Søndergård’s often brisk pacing, there were long passages where momentum flagged, becoming plodding and lacking the tension so needed to ensure the forward propulsion that should paradoxically emerge from Sibelius’s continual collapsing inwards. Key climactic brass passages (notably the so-called ‘swan theme’ that emerges fully at last in the third movement) were strangely muted – although some passages and certain of the trickier transitions had verve and spirit, showing flashes of what could be accomplished given greater depth and broader, longer-range sculpting.

Thomas Søndergård will surely continue to hone his Sibelius 5, both with BBCNOW and elsewhere – and it is good news generally that Sibelius’s true stature continues increasingly to be recognised. On the other hand, Sibelius is performed and recorded a great deal nowadays, in stark contrast to an exact contemporary of his who also produced major symphonies – and who, by chance, was actually Danish. So, whilst it was inevitable that considerations of popularity would shape tonight’s inaugural programme, it is nonetheless a pity that we will have to wait until next April to hear Thomas Søndergård’s interpretation of his fellow countryman’s important but little known Symphony No. 5 – composer of which being the troubled but brilliant Carl Nielsen.

St David’s Hall, Cardiff 12th October 2012

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Magnus Lindberg – EXPO

Grieg – Four Songs: To Brune Øjne

Jeg Elsker Dig

En Svane

Våren

R. Strauss – Three Songs: Muttertänderlei

Meinem Kinder

Cäcilie

R. Strauss – Till Eulenspiegel’s lustige Streiche

Sibelius – Symphony No. 5

Conductor – Thomas Søndergård

Soprano – Inger Dam-Jensen

Steph Power has written regularly on classical music for Wales Arts Review.

Recommended for you:

Steph Powers reviews the BBC National Orchestra of Wales concert in honor of the Dylan Thomas centenary, featuring the world debut of Burtch’s Four Portraits of Dylan.