Robert Minhinnick has twice been awarded the Forward Prize for Best Individual Poem and twice won the Wales Book of the Year for his collection of essays. His novel Sea Holly was shortlisted for the Ondaatje Prize.

An environmental campaigner, he works for the charity, Sustainable Wales and is co-founder of Friends of the Earth Cymru.

John Lavin: The idea behind A Fiction Map of Wales is to create a series of individual portraits of life in 21st Century Wales, thereby creating an honest, albeit fractured, vision of the nation as a whole. The thinking behind this is that art, despite the very fact of it being the product of someone’s imagination, can offer a truer reflection of society than either newsprint or historical documentation. Do you think that this is true? And do you think that it is important to write creatively about Wales – or indeed any location – in order to understand it?’

Robert Minhinnick: It’s more important to read creatively. But Wales is a thousand different places. I don’t think about Wales as a historian might, because too much essential detail is lost from history. Writers deal in particularities, and poems are about words, not ideas. The same for short stories. But ideas might be present, and vital to their existence and maybe genesis.

‘Long Haul Road’ is set on the Sker and Morfa beaches in your hometown of Porthcawl, an area that has become inextricably associated with your work. It feels fitting then that you would choose to set your ‘fictional map’ piece in what appears to be something close to a post-apocalyptic vision of those places. What were your reasons for doing so?

Sker/Morfa beach is west of Porthcawl. It runs from Sker west to the Afon Cynffig and then Margam steelworks. The story is part of a collection of writings titled ‘Mouth to Mouth’, being the mouths of the Ogmore and Cynffig rivers. It’s linked to two other stories, ‘Scavenger’, from the collection Island of Lightning, and ‘Balm of Gilead’, which I think will be published in 2015.

All three are written because I love the limestone-into-sandstone geology and the landscape of the ‘Mouth to Mouth’ area. I’m obsessed with what sand conceals and reveals. ‘Long Haul Road’ is about sleeping out in Kenfig dunes, building driftwood fires, the life of the beachcomber. Intensely particular things to evoke.

Post-apocalyptic? Why not pre-apocalypse? Yes, all three stories are set in a near, unspecified future. Writing about the future is exciting. Is it science fiction? Why not? It’s certainly fiction. Isn’t it?

In a sense ‘Long Haul Road’ almost feels like a companion piece to ‘Sker’, a poem whose protagonists you describe as being ‘Before history/ …naked children not seeing/ The storm…’. The characters in ‘Long Haul Road’ are also naked but this time they are ‘inheritors’ of a landscape that has been degraded by war and pollution. Is this an intentional link? And, if so, does it represent your feelings relating to the thirty-five years that have passed since the composition of ‘Sker’? Thirty-five years which have seen an almost constant escalation of both environmental and human-unfriendly capitalism?

‘Sker’ was written when I was 27. I’m 62 now. There’s another ‘Sker’ being published soon in the New Welsh Review – prose with images by Eamon Bourke. (But for me it’s a ‘poem’.) The new piece is much more ‘Sker-ish’, more real. No vague big ideas. The period between the two Skers contains all my work with Friends of the Earth Cymru and ‘Sustainable Wales’ from 1981 till now. I was a different person for the first Sker. The characters in ‘Long Haul Road’ must deal with a world that has altered quickly because of climate change. They know they are ‘inheritors’ and must cope with difficult circumstances. So yes, ‘Long Haul Road’ and the original ‘Sker’ are linked. The story’s characters see life as a challenge. Both are resourceful. Ffresni, in particular, is newly purposeful.

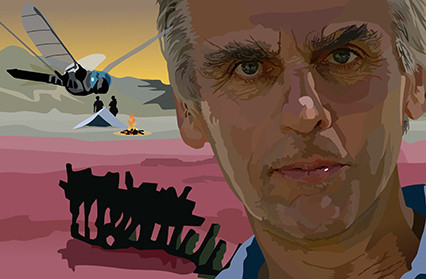

As with the pieces collected in The Keys of Babylon, ‘Long Haul Road’ feels like a deeply political story. In a funny way it also reminded me of your poem, ‘The Opera of Baghdad’, with its line about ‘The Tigres and the Thames’, and the sense which that conveyed of all rivers, places and peoples being interlinked. Looked at in this sense it feels almost as though the fate that befell Iraq has now finally – and inevitably – come to Sker Beach. Would this be a correct reading? And do you envision this apocalyptic scenario as a purely metaphorical one, or do you see things such as the small ‘black dragonfly drones’ that buzz around the saltmarshes as a likely feature of the not-so-very-distant future?

Do dragonflies buzz? I don’t think writers bother about ‘correct’ or ‘incorrect’ readings of their work. They’re merely pleased someone has bothered.

Drones based on dragonflies might already be happening. Technology is racing away. We have to deal with it, like the characters in ‘Long Haul Road’.

I’ve said elsewhere that Iraq changed my life. ‘An Opera in Baghdad’ deals with the effects of war on ordinary people. Ever been in a sewage pumping station in Baghdad? When it’s 100 degrees F? Humbling. Those men are heroes… ‘An Opera…’ was written for performance and works well live.

I loved the Baghdad markets and admired the resourcefulness of the marketeers. When I was in Albania I was amazed at the produce produced by people working in the worst of conditions. And boy, was Albania poor! I’ve written about a woman in a Zagreb market offering a single sunflower, a woman in a Lithuanian forest selling mushrooms off a tea towel. I tried to imagine their lives.

‘Mouth to Mouth’ is intensely local but depends on knowledge of other places. Porthcawl fairground is made more alive by my memories of Las Vegas casinos, and those markets where children flicked away flies from meat going green. All day. I thought of a short story about such a child dreaming of his future life. When I walk around the fairground I’m walking along Babylon’s Street of Processions. They’re not so different. And ‘Scavenger’ concerns what happens to that same fairground because of ‘inundation’…

I’ve written three stories with an ‘apocalyptic’ scenario. So I imagine alarming change. But I know any ‘apocalypse’ will be like nothing I expect. And no, I don’t believe in an ‘environmental apocalypse’, only climate change, possibly rapid. It’s merely a new situation to describe human lives. The stories are about people, not weather…

In a recent film for ‘Sustainable Wales’ I say that Babylon fell because of social inequality and that our culture is threatened by the same thing. That’s not to mention ‘climate change’ at all. But I’ve written the words for ‘Josephine’s Rain’, a depiction of a storm that hit Porthcawl in the 1990s. It evokes a hurricane and is bloody loud, with guitar, keyboard, percussion. In the last performance we had an artist on stage creating a painting during the thirty minute performance. Very 1960s. In the last twelve months there have been two other hurricane-like storms that affected the town. Reference to those is found in ‘Long Haul Road’.

You are the founder of Sustainable Wales. Do you think you that you could tell us a little bit about the motivation behind this, as well as the work involved? I ask because it is clearly important work but also because environmental preoccupations clearly define your work as a poet.

Margaret Minhinnick and I created Sustainable Wales http://www.sustainablewales.org.uk in 1994. (It was registered as a charity in 1997.) But it depends hugely on Margaret’s energies and enthusiasm. When I’m home writing, she’s in the office, ten minutes walk from the house, dealing with the thousand things you have to do when running an organisation that includes an office and shop. She’s in charge.

For ‘Sustainable Wales’ I bank its takings, take packaging for recycling at the waste tip, open up, close up, attend innumerable meetings, take minutes, organise events, think, write. Normal things. Which is good for me. Otherwise I’m in front of a computer in my attic, on another project… then another. When you’re a writer there’s always something new. Something else.

Of course, that’s the way you want it. But because of the charity I meet people and they’re usually wonderfully generous. Working for SW you realise how bureaucratic life has become. All those employment, environmental and arts agencies! And it’s getting worse.

As I get older I become more political. ‘Sustainable Wales’ is my political statement on the high street, with its shop selling fair trade, local, organic, green goods. That shop, ‘Sussed’ is open six days per week, employing one staff member. We also have a commitment to local art and literature via our ‘Green Room’ space. Kristian Evans writes a ‘Kenfig Journal’ for the SW website. http://www.sustainablewales.org.uk/a-kenfig-journal/ It’s very good. And yes, we put on Green Room events. Then there’s Sustainable Wales’s environmental work… It’s small. But beautiful.

Seamus Heaney, who died a year ago last August, described the role of poet as that of the diviner in the village. He describes the ‘craft of dowsing or divining [as] a gift for being in touch with what is there, hidden and real, a gift for mediating between the latent resource and the community that wants it current and released.’ Do you feel that this is true in relation to yourself and your view of the poet?

That’s attractive for those who consider themselves writers. I believe in ‘community’, which is the basis of the work of ‘Sustainable Wales’. But I can also imagine a ‘community’ stringing somebody up. Or ostracising them, which might be worse. I’ve learned never to describe myself publicly as ‘a poet’. Being ‘a writer’ is acceptable. My mother, recently in hospital, insisted on introducing me as ‘my son, the poet’. I read the faces of those people she spoke to and was not surprised.

Do you have a writing routine?

Prose? Get on with it. Mornings, early as possible. Afternoons, get out if you can. Walk. Poetry? I’m editing a very long poem at present which was written as a diary. It’s like putting a film or a novel together. The editing is everything.

Are there any writers that you would consider to have been a particular source of inspiration to you?

Reading is one of life’s greatest pleasures. With walking. They’re very similar, being forms of exploration. Names? Coleridge, Clare, GM Hopkins, DH Lawrence, Borges, Updike, Ted Hughes. The usual. Hundreds more.

Finally what’s next? Is there new work on the way?

A new novel, Limestone Man, should appear from Seren in mid 2015. It’s ‘Sea Holly 2’ in a way.

original illustration by Dean Lewis