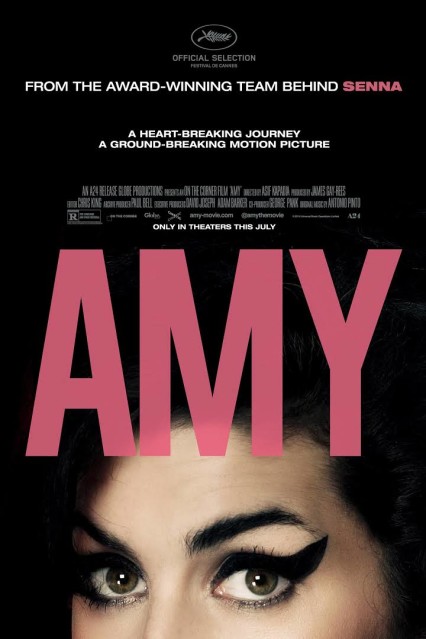

Craig Austin reviews Amy directed by Asif Kapadia, the bittersweet documentary about Amy Winehouse reflecting the heartbreaking snapshot of a beaming wide-eyed girl.

Around the time that Amy Whitehouse was entering her indisputable imperial phase, the point at which the unexpectedly thrilling emergence of Rehab had begun to morph into the elegantly wasted magnificence of Back to Black, I got talking to a man in a pub. ‘She’s got a marvelous voice, that Amy Winehouse,’ he told me wistfully, as the girl group heartbreak soul of Tears Dry on Their Own punctuated proceedings. ‘It’s just a shame about all the scribbling.’

Being someone who still has a soft spot for ‘the scribbling’, I felt compelled to disagree. For me, Amy’s tattoos were always one of the most endearing things about her. Much like the all-conquering beehived incarnation of the artist herself, they appeared to arrive fully-formed, and almost overnight. Not for her the gradually evolving ‘sleeve of boredom’ most frequently epitomised by young professional sportsmen with more money than imagination. In stark contrast Amy’s tattoos were amateurish, childlike, undoubtedly poorly thought-through, yet bewitchingly defiant in their execution. These were sailors’ tattoos, dockers’ tattoos, drinkers’ tattoos, the spidery antithesis of an alternative culture now seemingly sponsored by Urban Outfitters; the impatient insignia of a life (either real, or yet to be fully realised) that gave short-thrift to a notion as pitifully bourgeois as ‘tomorrow’.

Hindsight suggests that Winehouse may prove to be our last truly bohemian pop star, a dissident heart and instinctual spirit almost entirely devoid, despite the most craven efforts of myriad vested interests, of either a personal strategy or career plan. Yet despite the provocative affectations of her Camden Town twilight years, Asif Kapadia’s exceptionally tender documentary Amy succeeds in presenting the artist in her purest and truest form, as ‘a very old soul in a very young body’. ‘All I’m good for,’ she grins only half-jokingly, in an affectionate Frank-era sequence of archive footage, ‘is making tunes’.

‘Amy is a film about love,’ says Kapadia, ‘about a person who wants to be loved, someone who needs love and doesn’t always receive it’; and it is love, before the spiral of narcotic fug engulfed her, that is presented here as the singular rival for the artist’s deepest obsession and most primal addiction, her intuitive and all-consuming infatuation with music. Her sublime talent and ability to effortlessly blend musical styles from jazz to reggae to hip hop is sensitively depicted from a precociously early age, a world away from the flashbulbs, crack pipes and blood-stained ballet pumps that would later succeed in diverting the public gaze away from her spectacular creativity. A girl for whom there was never any expectation of fame, and for whom the trappings of celebrity proved to be little more than a calamitous by-product of her public elevation. A heartrending transformation from a wide-eyed fourteen year-old girl singing a Monroe-esque Happy Birthday to a small group of captivated school-friends to, as this film makes abundantly clear, ‘someone who was trying to disappear’.

‘Amy is a film about love,’ says Kapadia, ‘about a person who wants to be loved, someone who needs love and doesn’t always receive it’; and it is love, before the spiral of narcotic fug engulfed her, that is presented here as the singular rival for the artist’s deepest obsession and most primal addiction, her intuitive and all-consuming infatuation with music. Her sublime talent and ability to effortlessly blend musical styles from jazz to reggae to hip hop is sensitively depicted from a precociously early age, a world away from the flashbulbs, crack pipes and blood-stained ballet pumps that would later succeed in diverting the public gaze away from her spectacular creativity. A girl for whom there was never any expectation of fame, and for whom the trappings of celebrity proved to be little more than a calamitous by-product of her public elevation. A heartrending transformation from a wide-eyed fourteen year-old girl singing a Monroe-esque Happy Birthday to a small group of captivated school-friends to, as this film makes abundantly clear, ‘someone who was trying to disappear’.

Within an expansive (though equally fleeting) two-hour window, Kapadia succeeds in delving beyond the received wisdom of tabloid narrative, the director’s portrayal of the Winehouse story shot through with portentous echoes of Seán O’Casey’s assessment that ‘all the world’s a stage and most of us are desperately unrehearsed’. In doing so Kapadia admirably seeks to shun the crude caricatures of its principal players. The cartoonish pantomime villain of Blake Fielder-Civil features (off-camera, in common with all of Amy’s interviewees) as a broken world-weary narrator, his youthful North London swagger long-since replaced by a hesitant, damaged whisper. Yet Fielder-Civil appears alongside Winehouse not just as a cadaverous apparition at the door of The Hawley Arms, but also, in an astonishingly candid and sexually charged sequence of scenes shot in the studio of photographer Terry Richardson; a tantalising insight into the emotional fire of an obsessive all-consuming love. A fiery, wayward spark in a combustible union fuelled by the mad rush of love, of desire, and of a carnivorous lust for life.

However, the film’s most affecting section takes place in a drab-looking New York vocal booth as Winehouse gifts her bewitchingly unique voice to Back to Black’s towering title track. A display of raw emotional power that exquisitely captures the colossal voice that emanated from such a delicate frame. Alone in her studio isolation the artist is presented as a rare bird in a far from gilded cage, the last vestiges of personal freedom given free rein in advance of the incoming media storm. ‘Back to Black’ was not just ‘single of the week’ great, it was ‘Tracks of My Tears’ great, ‘Unfinished Sympathy’ great; a song whose subtle lyrical might – ‘We only said goodbye with words’ – effortlessly matches the timeless Motown measure of its plaintive magnificence.

In this sense, and given that Kapadia succeeds in consistently elevating Winehouse’s all-too slender body of work above the squalor and sharks that repeatedly sought to consume her, it is saddening to witness the recent unseemly scramble to define the narrative of what can only be described as a modern-day tragedy. An undignified bun fight most publicly played out by the artist’s own father, Mitch, who has publicly denounced the film on the apparent grounds that it fails to mirror his own interpretation of events and his role within them. It’s a peculiar strategy to adopt for a man who is seemingly seeking to jettison any perception that may exist of him being either controlling or (worse) complicit in his daughter’s demise. Especially given that Amy resonates with (for good or ill) the almost unconditional love that his daughter undoubtedly invested in him. A lifelong devotion indelibly inked into her slender scarred arms, a public proclamation of her one true love: ‘Daddy’s Girl’.

‘I love the way you sound so common,’ Jonathan Ross declares to a young and hugely endearing Amy Winehouse as she stretches across his chat show sofa as if it were her own front room. It’s a comment made in all sincerity and one that has acquired added resonance within an art form that has increasingly sought to close the door on those not imbued with society’s privileges. It’s a fascinating insight into the early vestiges of a quietly diluting culture, existing as it does alongside a hugely poignant photographic image from a period before the feeding frenzy commenced in earnest. A jarring, heartbreaking snapshot of a beaming wide-eyed girl about to blow out a single birthday candle that sits atop a huge chocolate brownie.

A candid point in time before the front row of her public stage became entirely populated by the enemies of art, the enemies of invention; a vampiric host of insatiable vermin, each falling over themselves to feast upon the golden crumbs that fell from the plate of the girl with the most cake.