Nia Edwards-Behi reviews some of the picks from this year’s Silk Road themed Wales One World Film Festival, with features from Tunisia, Palestine and beyond.

This year’s Wales One World Film Festival boasts an incredible line-up of films, with a focus on its central ‘Tales From the Silk Road’ theme. The programme is 50% F-Rated (so either written and/or directed by a woman) and showcases drama and comedy, documentary and animation and so much more in its selections. The festival begins in Swansea, at Taliesin Arts Centre, on March 13th, and plays also at Aberystwyth Arts Centre and Tramshed, Cardiff, before moving to Theatr Clwyd, Mold, in April. Below are capsule reviews of just some of the wonderful films on offer.

Beauty and the Dogs (Kaouther Ben Hania, Tunisia 2017, 100 mins)

Mariam is the organiser of a party at a hotel to fundraise for her university. The party seems to be going well, especially as she catches the eye of handsome Youssef. The pair takes a walk. We next see Mariam running down a street, dishevelled and crying. Youssef pursues her. We soon learn that Mariam’s trauma is not because of Youssef, but because of a group of bored policemen. Mariam has been raped, and the rest of the film follows her desperate search for help, compassion and justice over the course of the night.

Shot in 9 seemingly one-take chapters, Beauty and the Dogs is a remarkable film. While it tackles a subject which is perhaps somewhat familiar in a number of other films, its telling is quite unique, both for its locality and its formality. A film both specific to its Tunisian setting and yet altogether global in experience and reach, Mariam’s torment and trauma is harrowing to watch, and the film successfully avoids gratuity or excessive sentiment.

The central performance from newcomer Mariam Al Ferjani is instrumental in rooting the events of the film, which can begin to verge on the unbelievable as it progresses. Mariam is an immediately likeable character – sensible but no bore – and her transformation from enthusiastic student to trauma victim is played with real sensitivity.

The characters Mariam encounters are all varying degrees of unhelpful, even her white knight Youssef, who, though on her side, is more concerned with how he can use Mariam’s experience as a political symbol than in compassion for her as a human being. Mariam meets private clinic reception staff, exhausted public hospital staff, police, taxi drivers and more who seem to either be unwilling or unable to extend to her dignity or a helping hand. Rather perversely, the characters who seem most concerned for Mariam are some of the least able to help her – hands tied by underfunding or boorish colleagues.

Importantly, the film never forgets that Mariam is the centre of this story. Her search for justice is riveting and moving and, while she is surrounded by many others, driven entirely by her own sense of autonomy and humanity.

The Gulls (Ella Manzheeva, Russa-Kalmykia 2015, 87 mins)

In The Gulls a woman beholden to her brutish husband and traditional community finds herself with an opportunity for change when her husband disappears at sea. It is a stark film, an examination of tradition in a modern world, which tells its story perhaps a little too icily for its own good. However, its breath-taking Kalmykian landscapes imbue the film with life, even while matching the grey and cold tone of the story.

Elza is a woman haunted by familial duty, tradition, and perhaps her own inability to stand up for herself. The film begins with her failed attempt at leaving, but even so, her little transgressions – smoking against her husband’s wishes, for example – continue to point to a defiant nature just beneath her stoic surface. Elza is played by top model Evgeniya Mandzhieva in her screen debut, who might not quite have the required acting chops just yet, has just the right look for the role. She stands out, both in her impressiveness and her plainness, and yet is often silent or non-confrontational with others. This duality in her character is what makes her so striking.

It is perhaps not a wholly satisfying film, the story ultimately being quite slight, but as a portrait of a character and indeed of a region, The Gulls makes for fascinating viewing.

Israfil (Ida Panahandeh, Iran 2017, 100 mins)

An under-stated drama which meditates on love and loss, Israfil has a lot to its credit, while perhaps being a little too restrained at times. The film begins with Mahi, a woman who is grieving the loss of her son. A man from her past has returned to the small town where she lives, and tensions flare as the potential of a rekindled romance rears its head. But all is not so simple, as the man, Behrouz, is soon to be engaged to another woman with whom he plans to emigrate.

Although ostensibly dealing with a love triangle, there are no squabbles here, no drama, but rather acceptance, trust and understanding, even when characters are at odds. The film begins with its focus on Mahi, a woman not only grieving her son but also now confronted with painful memories from her past. When we are introduced to Sara, Behrouz’s current partner, we might expect fireworks or catfights, but instead, the film shifts position and follows Sara home to Tehran. There she has to deal with her unstable mother and a seemingly inconsiderate brother, neither of whom want her to leave with Behrouz. The narrative turn from focus on one character to another is a real strength in Israfil.

The film offers particularly striking echoes in each woman’s story – Sara’s mentally ill mother is manipulated by both her children, while Mahi is constantly reminded of her own history of depression by Behrouz’s return. Both women are wished dead by a parent in the heat of an argument. Mahi and Sara have more in common that film at first seems to suggest. The film’s final segment seems to finally shift focus to Behrouz, a man previously defined by how we’ve come to know him through Mahi and Sara.

The film is messy in its conclusion, but in a way that’s quite satisfyingly true to life.

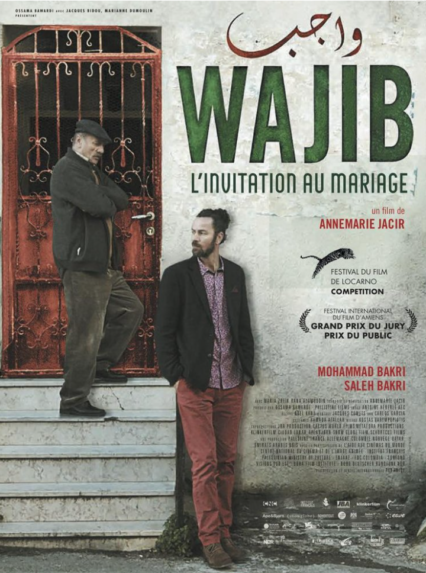

Wajib (Annemarie Jacir, Palestine 2017, 96 mins)

Wajib is a domestic road movie, as a man, Shadi, returns to Nazareth from Rome to join his father in hand-delivering wedding invitations to friends and family for his sister’s wedding. Along the way cultural and generational tensions flare in this under-stated and brilliantly performed drama, showcasing a different sort of depiction of Palestinians on-screen than we might be used to.

Shadi seems irritated by his father’s traditionalism from the very start, but his father gives in return: the occasional comment about the nice girls they pass, or the shirt he’s wearing. The combination of both cultural and generational conflict plays out in a very believable way, perhaps aided by the real father-son duo of Mohammad and Saleh Bakri playing those roles. There’s a lovely sense of humour played throughout, and while secondary characters naturally come and go, there’s a very well established sense of community from them.

There is a key missing character in the film, that of the mother, who seemingly left the family years prior to move to the US. The shadow of this abandonment still remains as gossip amongst those in Nazareth, though you get the sense that Shadi takes after his mother. Elsewhere, we warm to Abu Shadi, the elder, as he successfully comforts his daughter when a hiccup arises in the wedding plans – a hiccup that will not only drive the biggest wedge between the two men, but also reunite them.

The film, rather satisfyingly, does not prescribe a particular view to take when it comes to Palestine. Do we, the foreigners watching, side with the politically-minded, defiant, but now outsider, son, or the practical and traditional father, who does what he can to just get on with living? The film doesn’t spell it out.

Wajib ends with quite a deliciously satisfying closing scene, underscoring that this is a film about family and people over politics and nations, while all the same suggesting that these things are not so inseparable.

Part one of Nia’s review of Wales One World Film Festival can be found here.

To find out more about all of the films playing at Wales One World – including Oscar-nominated The Square, Studio Ponoc’s Mary and the Witch’s Flower, Hirokazu Kore-eda’s The Third Murder, Warwick Thornton’s drama Sweet Country and documentary The Prince of Nothingwood – head on over to www.wowfilmfestival.com or find the festival on Facebook and Twitter.