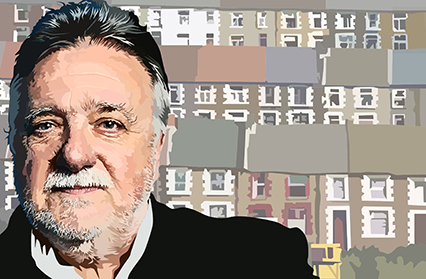

Earlier this month Dai Smith retired as Chair of Arts Council Wales after 10 years in post. Here Wales Arts Review publishes his farewell address, ‘A Common Wealth of Culture’ unabridged and as delivered at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama in Cardiff on March 31st, a vision of the future for a vibrant culture in Wales.

*

Ten years ago I delivered my first Address as Chair to the annual conference of Arts Council of Wales. It was a time of some turmoil for the arts in Wales – some necessary confusion I might, looking back, now say – and there were uncertainties to confront in the eye of that storm. So, I lashed myself to the mast. I made certain promises, issued a few warnings, reflected widely on what Wales itself had been and what it might yet become. With the help of the arts. Fuelled by creativity. Sustained by culture. A Common Wealth of Culture. Titles. I called that talk ‘Valued Art: Valid Society’. Well, was it? Valued, I mean. And are we, ten years on, more so as a society? Valid, I had suggested. Ten years before the mast. To begin with, then, a review. To end with, I promise, a fresh perspective.

What we had in Wales a decade ago, was the continuing reverberation of a widespread debate over the instrumental possibilities of art – as intervention in health, education, deprivation – and the intrinsic qualities or essence of art – as expression, statement, challenge and so on. No one really argued against what palpable good the arts might do, and there was already committed and effective work being done, in the broad field of regeneration, mostly at government’s urging. They sought measurable results for public subsidy. Reasonable enough, so far it goes. But the separation of artistic purposes became entramelled in a skein of compromises that befuddled a tyro government’s understandable desire to use culture as a part of its strategy for Wales, and the worried insistence by others that only an arm’s length stance would allow for artistic freedom and a civic balance to the politics of an electoral democracy. The result was a quarrel.

What I decided, after that quarrel and in the aftermath of the diplomatic Stephens Review, was that the Arts Council of Wales would no longer accept the language or the limitations of that debate. To be set ‘at arm’s length’ was to accept the descriptive stasis of nouns when the dynamic of verbs had already come into play. To be an arm of governmental needs would only act to serve every twitch in policy at the expense of a more profound and principled philosophy of commitment to the arts in and for themselves. My contention, then and now, was that these were dichotomies we could ignore if we accepted instead that the arts were only, ever, of instrumental value if their intrinsic merits were first recognised. Art generated matter through creativity; it did not re-generate anything, unless, of course, you mistook an image in a mirror for the real thing. And the real thing was, and is of course, an agenda for change. Change is at the core of all serious and seriously desirable arts practice. It is why there is both an appetite for it, and a fear of the new culture it heralds. Government cannot by its nature, be the custodian of this. But democracy, through government, must seek to engage with it, however it turns out. You cannot audit the arts for risk or for health and safety. We invest in them as a society precisely because they are a risk. If they are any good – and I told that long-ago Conference we would not be in the business of shoring up mediocrity or shirking away from the judgement of prioritisation – if they are truly of excellence then they will be inherently risky, a danger to the sedentary of spirit and the stony of heart. I said I wanted Arts Council of Wales to be in the van of that front line and to lead under the banner of excellence of achievement, of ambition and of potential.

I will come, in a while, to what I think an independent and engaged, a funded and accountable, a transparent and a listening, Arts Council of Wales has helped to facilitate and sustain in the arts. We can only take limited credit for such things since we are not, of course, the creators of the art. But, and it is a very big But, we can, and should, be credited with the cultural and organisational changes necessary to make us the trusted facilitator and sustainer. Over a period of years we have transformed the internal culture of the Arts Council of Wales and altered its organisational focus to deliver national arts strategies locally. Under the rubric of Transformation and Renewal, brought to fruition over 5 years ago, we looked at ourselves and not only at our directly funded recipients. To be creative, as an institution in the new Wales, we needed to change in function, in personnel and in culture. I believe, under the executive leadership of Nick Capaldi and with a dedicated staff, we have done just that: to prove our institutional value, itself the key to any leadership of the arts community by cultural professionals. All the indicators – other than investment – are up. Client satisfaction, participation, attendance, earned income.

We are indeed value for money. And this year, even when accumulated cuts from a cash-strapped Welsh Government amount to 12% over the last three years, we have protected front-line services by a judicious mix of re-allocated project funding, lottery distribution and eye-watering efficiencies. It is run as a tight ship. And has been since, under our successive strategic art reviews, Imagine and Inspire, we have reduced our client numbers from over 100 to 67, and ensured their stability. No one with eyes to see and ears to listen and feet to move can be in any doubt that we have been living through an exceptionally vibrant time for the expressive arts here in Wales. It has not happened by chance: it is the product of government support and of sustained engagement with the arts, by many individuals and organisations, across Wales. And not least by the unremitting and unselfish work of the Council members who have served and worked with me on Council.

You’ll remember what appointed Councils were like, back before 1997, or if not I’ll quote the words of Wales’ greatest 20th century intellectual figure, Raymond Williams, who wrote of such cultural life:

From the 1940s there had been an understanding that there were people of experience and social position – the ‘Great and the Good’ – who would be trusted to run things on the Government’s behalf without interference. This was because they the ‘Great and the Good’, instinctively knew what the Government wanted and could be relied upon to deliver it … in metaphor this is known as ‘the arm’s length principle’, an unfortunate image … more like, in practice, a wrist’s length.

We needed to acknowledge fully that Devolution, after 1997, had brought in a democratic mandate with which, even in the arts, we had to be constantly engaged. But devolution is not in itself democracy; it is, like all other forms of representative government, only a means towards that desirable state. It was incumbent upon us to find a new metaphor: the handshake of engagement and mutual trust. Trust has to be a Two Way Street. And then, when cultural organisations do successfully mediate between the intrinsic purposes of culture – to create expressive meaning – and the instrumental outcomes that can only follow after that, they do generate fresh institutional value in the form of social capital. Social Capital whose principal feature is trust, is, in turn, essential to the enlargement of the public realm. On both sides of the equation we have been engaged in nothing less as this old country shapes up to become a new polity.

Arts Council of Wales must represent the actual plurality of Wales – and it’s no coincidence, for instance, that we have consistently appointed more women, earlier and longer, than any other comparable public body, and way before targets were set – atoms, if you will, in search of civic fission, not clusters of interest groups networking across the symbolic vacuum of Wales. Politics, even before the democratic mandate, was never set apart from culture in reality, and, in reality, the professed autonomy of the arts and their alleged eternal verities was too often used as a smokescreen to allow them to be possessed and distributed on a conveniently limited basis.

Too often the subsidised arts have been the personal capital of the few and not the social capital of the many. Nor are there guarantees that once secured that social capital cannot be privatised and shared out as a windfall dividend. When popular and performance culture, from bands to acting, becomes desirable, profitable and do-able, Eton proclaims it, alongside the City, the Army and the Professions as an essential part of its curriculum. And as the recent widespread concern about the rise and rise of the well-heeled and well-supported in the acting profession has demonstrated, the paths to glory for the Stanley Bakers, the Donald and Glyn Houstons, the Rachel Roberts’, the Michael Sheens and Richard Burtons are not so apparent now, in Wales and elsewhere. It is not a question of talent or even just one of opportunity – that would be the mistake of individuating the dilemma – it is to do with whatever we once meant by, and must interpret again and afresh, as community.

In her brilliant recent book The Actors’ Crucible, Professor Angela John demonstrated how, as she put it, ‘this much-maligned steel town (of Port Talbot) … generated a glittering array of men and women with careers in drama … and their relationship to their community.’ Even for those who thought they knew – of Burton’s mentoring in school drama, and Hopkins’ self-discovery at the YMCA and Sheen in Youth Theatre – her retailing of the plethora of amateur and semi-professional dramatics in Drama Clubs, in working-class organisations, in churches and chapels and eisteddfodau, in festivals and on the boards of established and travelling theatres is truly astonishing. Until we realise that there were equivalents from the Rhondda to Rhosllanerchrugog in that Wales, which, truly, was a community of communities. When National Theatre Wales, itself just ten years old, put on The Passion in Port Talbot they were only coming home, at last, and thousands on the streets let them know it. When they fight for the material culture of steel now, they are doing so as a culture in which self-expression has long validated their community sense of being and belonging.

There was an appetite for art that stretched and expanded minds and emotions, and it is out of that cultural environment after all that the now world-acclaimed Welsh National Opera came in 1946. It is not nostalgia that should make us recall such significant times, it is the resonance of lasting values, of intellect, and of the counter forces that conspired then, and can still do, to veil their snobbery and disbelief with a patronage offered from above to those apparently set below.

Let me remind you.

In November 1948 the Mountain Ash Urban District Council in the Cynon Valley, where the famous Three Valleys Festival of Music had been held before the war, decided to exercise their rights to culture under the Local Government provisions which the Labour Government had brought in. This is what was minuted:

The Urban District Council exercised its discretionary legal powers to provide entertainments. They contacted the Arts Council of Great Britain … about an Arts exhibition or sculpture in the area, and asking for Arts Council advice and support.

They had their reply in January 1949 when, (and I quote, because you couldn’t make it up)

Huw Wheldon, the Welsh Regional Director for the Arts Council attended and asked (the Council) to support a marionette show and the Luton Girls Choir.

We’ve been here before then, balancing basic human needs with human potential, succouring social imperatives and yearning for deeper, cultural fulfilment. But when we think back on our history, the grim 1920s and 1930s say, we get it all wrong if we wax nostalgic about how communities were built despite endemic poverty and miserable lives: the truth is that communities and their culture – of chapels and Institute Libraries, and trade unions, and brass bands, and choirs, and theatre, and sport – were the vehicles of survival that pre-dated and post-marked that battered Wales. They were not a by-product of conditions, they were the very condition of existence itself. It was culture that blew in the nostrils and culture that filled the lungs and art – from Geraint Evans to Emlyn Williams to Richard Burton to Kate Roberts – that articulated Wales, that actually still captures our memory, our landscape, our lived experience, out languages, as the hallmarks of our specific difference, and of our common humanity.

That is why at the very same time, as we came out of that slough of economic despond, in the 1940s the man universally hailed as the 20th century’s greatest Welsh citizen, Aneurin Bevan, talked about Art in the same manner that he talked about Health.

As an urgent priority, Bevan created the National Health Service not as a comfort blanket against illness and old age but as a cloak to allow a society to protect itself so that it could live freely and naturally, not in fear and dread of the unwarranted. But the key word is ‘live’ not ‘security’; the NHS was to be a springboard for living in a way all people had the right to live their lives, in individual fulfilment within a civic society of purpose. 1948: the foundation of the National Health Service.

1948: and this is Bevan that same year on the cultural entitlement he felt local government should provide:

Some day under the impulse of collective action, we shall enfranchise the artists, by giving them our public buildings to work upon: our bridges, our housing estates, our offices, our industrial canteens, our factories and the municipal buildings where we house our civic activities … it is tiresome to listen to the diatribes of some modern art critics who bemoan the passing of the rich patron as though this must mean the decline of art whereas it could mean its emancipation, if the artists were restored to their proper relationship with civic life.

That ‘proper relationship’ is, properly, with the audience, the public. The Arts Council of Great Britain set up two years previously in 1946, generously thought of how it might help in creating a new Britain with more and extended opportunities for people to enjoy the arts. Yet that was not what Bevan meant – the exchange of one kind of patronage for another – he talked of ’emancipation’ and ‘relationship’ and he surely meant that the wider and deeper the audience the more art itself, in all its manifestation, would change. The coterie theatre of Jacobean London was one thing, the groundlings at Shakespeare’s Globe were another; social change changes art in the best possible way: it inflects its own contemporary, sometimes inchoate, need for expression into that art and, seeing the reflection, distorted or otherwise, it validates the art. I do not mean that only popularity makes art valid but I do say that an arts policy from government will both be better understood, better funded, better supported and ultimately the generator of better arts practice if the encounter with civic life is seen to be sincere and ongoing, and on both sides of the equation.

Culture then, and only then, could become the key driver of social and economic regeneration because it will be the generator of ambition and hope in itself, not merely for its supporting role in infrastructure and employment. A society that possesses ‘culture’ as its real texture can receive and hold and build its own material and structural direction. I am convinced that a Wales which is, at last, institutionally present but, at present, still historically fragmented demands this texture if it is to achieve new definition.

At present we allow ourselves to be corralled by the advertising slogans of superannuated Mad Men.

Team Wales. Brand Wales.

Wales is Open for Business

What are we? An adhesive logo? A cheapjack franchise? A desperate corner shop? The flabbiness of the language exposes the hortatory chants of the intellectually insecure and the emotionally stunted. What Wales is is what we choose for it not what it consigns us to be. It is a conversation amongst ourselves on which we would like others to eavesdrop. They’ll only do that if we make it interesting enough for them to want to join in. We shouldn’t tout for business. We should do the business. Our unique selling point will be the distinctiveness of ourselves, our take on the world, our cultural and historical DNA, translated into skills and scholarship, which both connect and reflect, from our Museums to the Manics.

Poverty of Imagination remains the greatest shackle we have on our well-meaning, but less than adequate, efforts to devise a holistic policy agenda that can break the stubborn stranglehold that is the poverty of experience so that we may nurture, again, a collective aspiration for both individual potential and social growth.

Nye Bevan, again, this time in Trevor Griffiths’s award-winning screenplay, which I commissioned for BBC Wales in 1997, Food for Ravens:

Once I asked a simple question: What do we put in place of fear?… If we let ourselves believe that reading and writing and painting and song and play and pleasuring and imagining and good food, good wine, good clothes and good health are the toffs’ turf … haven’t we lost the battle already? They’re ours. Human birth right. All right.

In a world of measurers and bean counters we need, as he did, to go star-tapping. We are simply not bold enough, often enough, to think outside the comfort of our assigned boxes – administrative, educational, governmental, cultural, environmental, architectural, local and global. To be imaginative in this context, and especially here in Wales today, is to refuse the public separation of functions which are, in our individual private lives, always lived as a whole. Living in poverty, and the material kind is usually the anti-aspirational sort, is to be denied that wholeness. This may present itself as poor health or education slippage off the edge as early as 13 or 16 or 6, but at root, in this society, of opportunity and privilege for some, it is being unable for too many, as individual or communities, to shatter not just the glass ceiling, but the glass wall where you can look, but you better not touch, boy.

There are no quick-fix panaceas. If there was a formula we would have marketed it. What we can say is both that Wales is more fragmented – geographically, socially, historically even – than we sometimes care to say out loud lest the brittle national unity by which Cymru embraces Caerdydd and Cardiff becomes emblematic of a new Wales is lost in a tribal squawk and a pork-barrel squabble. The process we confront now, in the most profound sense, is about civic choice – who you are and why – of discovery – what you make and think of all this – and in many many forms and guises, singular and plural, in order to ensure the hold-all term of ‘Wales’ liberates rather than confines the new Welsh people who are, in surprising and unexpected manner, now emerging.

And it will be the case, of course, that a species of cultural consciousness of some kind will evolve. But if we choose to shape it for ourselves, the tools most acutely and tellingly available will be those through making and participating in the arts, with creativity the essential building block for an aware and participatory democracy, for a democratic culture, one most urgently to be put in place where poverty and social exclusion have temporarily shut out memory and hope.

Look, let me be clear, I do believe that our history demonstrates we have understood that power does not reside in constitutions, nor rights in law, nor human connectiveness within boundaries. It is not identity politics that can take us forward but the identification of people with the consciousness of political purpose. Our particular communities once had that, and were known internationally for it. There is no contradiction between a Wales that reaches out and a Wales that understands itself and its own contradictions properly. The alternative is navel gazing. The thin gruel of sociological commentary in place of the rich narrative of social history.

None of that can be recreated. It can only be created anew. It is why now intervention, of the creative kind, is so vital within our last remaining species of organic communities: our schools. Perhaps the single most important initiative we were able to undertake, as an Arts Council, come in the wake of the Report on Arts in Education which the Welsh Government commissioned me to lead and write. When all twelve of its far-reaching recommendations were accepted, it was Arts Council of Wales which was asked to lead, alongside the Education division of government, on the Creative Learning in Education plan which is rolling out across Wales over the next five years. It is fantastic that Government has match funded our own contribution, via Lottery, so that the scheme, deep and far-reaching, will be financed by £20m pounds overall. As crucial is the adoption by Professor Donaldson, in his subsequent Review of the Curriculum, of Creativity as one of his key themes, with the expressive arts to the fore. I am utterly confident this is a game changer and that Wales, within the next decade, will be an exemplar, worldwide, for creativity in education through the impulse of art. It is the kind of compact with Education which we at the Arts Council once proposed, to general acclaim, with Health. That was back in 2009. I believe strongly that that should be the next major proposal the Council should, shortly, be making again. And in the middle of all this, following along with Baroness Kay Andrews’ Report on the linkage between cultural deprivation and material poverty, is the clear evidence that Wales itself will not cohere, as we would wish, if we pretend that a legal and constitutional presence is any kind of guarantee of national purpose. The Wales we have, in many ways, so recently invented may exist – how could it not? – but it does not, and will not, live in a proper sense if we mean, as I do, by ‘live’, that it must have a meaningful relationship with its own battered, yet resilient, past if it is to have a future reinvigorated by moral and social purposefulness in this disjointed present time.

If there is an overwhelming public cause for the arts it lies here: if audience is to be more than a coterie, a clique, a family of interest, then the invigoration of community and its entitlement to creativity will be of the essence. This is not, then, just about Community arts or even arts in the Community, it is about the key role the arts should play within the Public Realm.

I have also been saying, for a long time now, that art which is not imbued with the intent of excellence is not worth having. That is not elitist; anymore than elite performance in sport is any kind of denial of wider participation. Always there is the purpose of connection.

But I sense that not all the obviously clear values for the arts are seen as self-evident social validators. For that to happen, in an inevitably more and more fissiparous world, we will need leadership not only from Arts Council of Wales and the arts sector but also, and more forcibly from a wider society, and from our elected politicians. But this time, seeing and arguing the intrinsic case for the arts since, within the particular circumstances of this Wales, it is in our common deepest interest so to do. The Heritage that is the cultural legacy of artistic making will not survive if the creativity that delivers such heritage is not nurtured and sustained. If our nascent democracy in Cardiff Bay is to do more than limp along from crisis to puzzlement it absolutely requires vision, the definition of purpose, disputed and debated but still purposeful, which a shared culture brings to the democratic table: and from all that stems vibrant elections and widely cast votes and truly popular manifestoes and, yes, a plural identity within our singular country. Without the arts Wales can, successfully, be none of those desirable things to the full. To be culturally disempowered, however inadvertently, for any vital community is to be de-powered unnecessarily.

And the evidence is all around us; we can see how vital the arts are when we consider the flagship impact of what, through the Arts Council, with our Government’s support, we have been envisioning and creating in the past few years. World class, fit for purpose organisations that can take to the world stage or be at home in the world class venues we have built. From the Venice Biennale to Artes Mundi to Womex. International staging posts for Wales’ profile. Calling cards like no other. As Carwyn Jones has said, ‘In the arts, as in sport, we punch above our weight.’ An artistic ecology within art forms now sustains and develops this work. Together, in volume and in quality, Wales has never had anything like this before. It is literally breathtaking to think that, since Devolution of Government, we have been able to add to the indisputably great artistic organisation of WNO and the National Orchestra of Wales, a revitalised Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru, a totally invented here National Theatre Wales, the joined-up thinking behind Literature Wales, the artistically acclaimed and now organisationally sound National Dance Company Wales and a veritable diamond scatter of venues and arts centres and galleries the length and breadth of Wales largely made and supported by the Arts Council in our role as Lottery Distributor. There is, too, a roll call that could, if I had time, be a drum roll of achievement, individuals and companies, across all the art forms. And over £3m in Creative Wales Awards to over 200 recipients in the last 10 years. Innovation needs such support. The unconventional require such backing. Communication is about content or it is White Noise. Technology is a conduit to a means not an end product.

And, you know what, sometimes these achievements, for that is what they are, have happened against the odds. A nation of under three million people, less than the population of Birmingham as they say, not concentrated to anything like the degree of say, Ireland’s powerhouse in Dublin, and working across the arts in two languages. All in financially difficult, and now extremely harsh times. How have we managed it then?

Well, let’s take the language conundrum first, because it contains within it, I believe, a vital clue to wider future success.

Modern Wales is a multi-cultural and multi-lingual society within a formally bilingual nation. If our arts practice can capture this then the progression and extension of yr hen iaith becomes a very special and singularly Welsh key to unlock the connective yet disparate strands within our common culture.

There are particular strengths vested in language and identity in Wales. In an increasingly globalised world, the Welsh language, alongside English, is a basic civic attribute as well as an inherited culture. If we are to flourish and grow changing and challenging, our Welsh and English language cultures will need to look increasingly to innovation and responsiveness – to reflect the global trends and changes that guarantee relevance and the usefulness of provocation. As a dynamic source that feeds and inspires us, we should then welcome what comes from tradition, but not ever use it as an excuse for introversion, conventionality or complacency.

The Arts depends on the fresh flow of new ideas. That’s a creative challenge for all Welsh artists regardless of their formal communicative language if we are to attract the world’s attention. Or, as that anglophone writer from Pontypridd, Alun Richards, said of his great friend, the Cymraeg patriot and rugby genius, Carwyn James of Cefneithin, ‘He was a Welshman who made you feel glad you were a member of the human race.’

To say that other alternative funding scenarios are, for Wales especially, not easy to find is not the shoulder shrug of the overly dependent, it is the look-me-in-the-eye truth of those too long in the tooth to be dewey-eyed. Public funding of the arts no less than for the NHS is the Foundation Economy of any society intent on change in Britain and Wales.

Suppose, just suppose, a new Maecenas, that supreme Roman patron of the arts, landed unheralded amongst us from Mars, and offered to fund the arts in Wales, inflation-proof, for the next ten years, with only one, non-arts provision attached. And that would be that not a single penny from the public purse should go to culture and the arts. Before we let our finance officers form a queue to that seductive pay window I would be standing in line to help turn the applicants away. No self-respecting society could or should side-line the arts in such a way. No culture should allow its citizens to consider the arts as anything but integral to its being. When we, as citizens, invest in the arts we honour ourselves.

Only the proper, and I do mean proper, more expansive public funding of the arts, will guarantee the provision of the risk takers we need to guide us, to thrill us to provoke us, to scare us, to delight us. Only the properly resourced public funding of the arts will allow us to enlarge understanding and appreciation of the arts, not only by access but by full engagement with what will then become an acquired openness of mind, and all so easily achieved by the acquisition of those cultural means for all that are so readily available to help those few who then just glide through open portals to social and economic advancement. As if privilege and inheritance have nothing to do with it. Well, let us privilege ourselves. Let us herald the legacy of the means we have hitherto created in common.

The arts are our common wealth as a Welsh people become they are our wealth in common. We must share them. We should not hoard them. A miner’s banner from Penrhiwceiber once said it clearly, in terms of once even harsher struggles for the common right of entitlement, when it proclaimed ‘Knowledge is Power’.

And we empower our democracy every time we make the arts central to our being, as individuals and as a society. Why do we ever forget this? Who makes us forget it? Why should we be made to fear the very thing that makes us human: our brevity of years and the defiant songs we sing against time, which otherwise effaces our presence. ‘Poems and materials of poems shall come from their lives, ‘sang Walt Whitman, the great American bard of the common people, and so, ‘They shall be makers and finders.’

Art is at the very core of whatever Wales and the Welsh have been over the centuries – we cannot imagine those past lives without their literature, their music, their dance, their painting, their songs, their imagery, their craft, their poetry. Wales is a mere landscape without that mindscape, a geographical expression not a human entity, a sentiment not a society.

That tradition, that culture, is of course, ours to share and proclaim and, in its heritage, to be treasured and made available to all. But that is not the most important thing to say about our Common Wealth of Culture. And what I have been pointing to is that culture is about what we mean to be, not only who we once were. Creativity is of its essence since we explore the new meanings we must find, in order to move on, only by changing the meanings by which we have habitually lived, as experience leads us to do if we are to possess that common meaning, of togetherness, even in dispute, which is the hallmark of any society of purpose.

Culture is, as Raymond Williams once told us ‘ordinary’. But he also said that such ordinariness is only ‘where we must start.’ That whole way of life, which is a culture, is also quizzed and altered and enhanced and challenged by that art and learning and education which is the catalyst for change within the wider culture.

When we fully understand that, and then answer the question ‘Who’s afraid of Culture?’ we will expel the money changers of socially counterfeit coin and the philistines of know-nothing cynicism from the once great Temples of Common Purpose they have so diminished with their hucksterism, and we will set afresh the direction of our human compass.

Let us do that, with increasing conviction and energy here in Wales, and act bravely towards that end. So, finally, a personal Manifesto from a retiring Chair, one blooded but unbowed, and still confident we can cause it to be enacted if we the people so choose.

Arts Council of Wales Arts Council of Wales Arts Council of Wales

A Manifesto for the Arts in Wales

- The Arts Council of Wales will continue to be recognised and trusted as the facilitator, sustainer and developer of the arts in Wales.

- That any incoming Government will have in its cabinet a Minister (and not a Deputy one) for Arts, Creativity and Culture.

- That all other Government Departments will – with cash and commitment – embed a vision for a creative culture within their areas of remit, and not just the other way round!

- That the Arts and Culture Minister will report directly to the First Minister on how the vision for a Creative Wales is being led and administered by ministerial colleagues.

- That the arts are secured by 4 year funding arrangements to allow for growth and planning through the leadership of the Arts Council of Wales.

- That creative freedom is assured within an overall and agreed Strategic Plan for the Arts and society.

- That work is undertaken to fill the still considerable gap in the nation’s cultural infrastructure by, for example, creating a National Gallery of Welsh Art and Imagery, with an adjunct contemporary Gallery.

- That Creative Industries are included in the Arts and Culture Minister’s Portfolio and that the defunct Creative Industries Panel is given new direction, as envisaged by the Hargreaves Report, in conjunction with Arts Council of Wales.

- That Arts Council of Wales is formally instructed to initiate a widespread programme of mentoring to make arts practice and professionalism in the arts widely and equally available to all.

- And that we explain to all our citizens, young and old, why it is that bigots and nay-sayers the world over will always reach for either the direct threat of the gun or the indirect strangulation of austerity when they hear the word culture, and how, in Wales, we will, through our common culture, forever oppose them wherever they are.

Professor Dai Smith

Chair, Arts Council of Wales 2006 – 2016

Arts Council of Wales Arts Council of Wales Arts Council of Wales Arts Council of Wales