‘Would you like to see my dragon?’ asked the young woman. I had just launched The Dragon and the Eagle app on Wales and America at the North American Festival of Wales in Minneapolis, and she wanted to demonstrate her own commitment to the Land of her Forefathers. ‘Yes please,’ I replied. She turned her back to me, lifted her blouse and let me admire the huge red dragon tattooed across her back.

The emotional commitment to Wales manifest at the Festival, sometimes from Americans whose Welsh connection is way back in the remote past, is extraordinary. Participants travel from every corner of the United States (and Canada because the Festival extends beyond the 49th parallel), and when they sing old Welsh hymns at the Festival’s two Gymanfa Ganu events, the walls of the huge Westminster Presbyterian church in Minneapolis seemed to tremble with the power of the four-part harmony.

‘Though vast oceans lie between us

In our hearts we hear you call,

And we answer one and all…’

sang the Welsh-Americans at one of the many musical gatherings in Minneapolis.

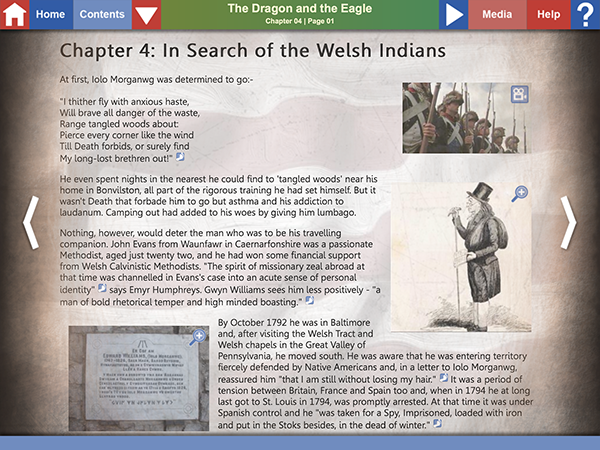

The app only just made it to the event in time – Apple accepted the outcome of Cardiff-based Thud Media’s labours with just twelve hours to spare. To my huge relief, there it was on Apple’s app store on the very morning of the launch date. The project had developed out of Dreaming A City (published by Y Lolfa 2008), a book I had written about Hughesovka/Stalino/Donetsk. This had included a DVD on the same subject inside the book’s back cover but I wanted to integrate video and text in the same package.

And writing about the Welsh in Ukraine – John Hughes had brought over dozens of them to build his steelworks and the town that took his name – had made me curious about Welsh emigrants elsewhere. Those who came first to Pennsylvania were mainly Quakers fleeing from religious persecution, and they soon faced the dilemma that confronts all migrants everywhere – how do you become good citizens of your new country whilst still holding on to your own language, culture and values?

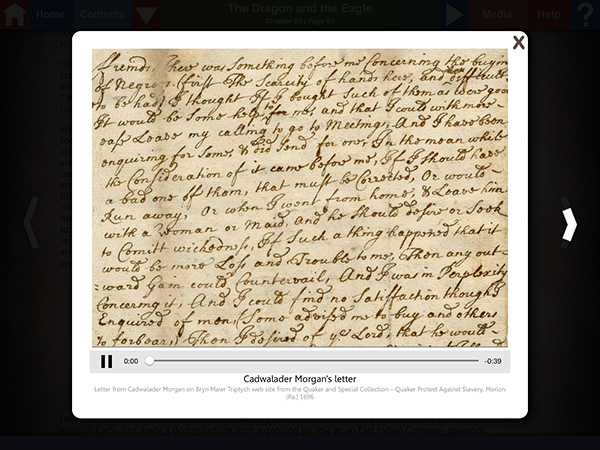

It was an issue over which Cadwalader Morgan, a Quaker farmer from Merioneth who had emigrated to Meirion in Pennsylvania, clearly agonised. He seems to have found it difficult to find enough helpers to bring in his harvest so asks his new neighbours, many of them fellow Quakers, what he should do. Buy a slave, they seem to have advised. He is clearly taken aback and writes ‘I am in perplexity concerning it.’

With the possibilities opened up by this new form of publication, it becomes feasible to bring this key moment to life – a tap of the screen reveals the handwritten letter, a further tap and you hear the letter being read. And a short video, compiled from the archives of BBC Wales, ITV Wales and Sianel Pedwar Cymru, that introduces the chapter on Welsh Quaker emigration puts the letter into its historical context.

It is at least possible that Cadwalader Morgan’s letter was the starting point for American Quakers beginning to question their role as slave owners and, up to the end of the nineteenth century, there seems to be a pattern of Welsh radicals challenging the values of their host society – Morgan John Rhys helping to establish the first black church in the Southern States, Evan Jones translating the Bible into Cherokee and following them into their brutal ‘Vale of Tears’ exile, Martha Hughes Cannon not only arguing for women’s suffrage but also standing as a Democratic candidate against her Republican husband. And winning too!

Welsh-Americans were overwhelmingly on the side of the North during the Civil War, a war that the publishers, Thud Media, have been able to illustrate with vivid interactive maps. But the victor in that war was the Republican Party and it wasn’t long before what was formerly the voice of dissent became the voice of the upwardly mobile. The Republican Party’s candidate for the Presidency in 1916 was Welsh-speaking Charles Evans Hughes and I managed to find, and include in the app, archive film of him on the campaign trail.

But the man who The Cambrian described as ‘the greatest Welsh American in the whole history of the United States’ lost the election to the Democrats. And by that time there were Welsh Americans further to the right than him – men like Hiram Evans, Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. The Dragon and the Eagle is not a work of hagiography which merely venerates Welsh-American heroes.

Rather it sets out to illuminate the history of two nations by coming at those histories from an oblique perspective. By including in the app clips from films like How Green Was My Valley and Proud Valley, I believe that it also provides insights into the way both countries have perceived each other. And it backs up the summary of the case it makes in the video introductions with a more detailed outline of the argument in text form.

Above all, I hope it provides an insight into the experience of migration that many refugees and asylum seekers are going through in Wales today. Even if they do not know the meaning of the word, those new migrants here would be able to share the intense emotion with which the Welsh-Americans in Minneapolis sang of Hiraeth – and understand Cadwalader Morgan’s sense of bafflement at the very different ways of their new society.