Gary Raymond is at the National Museum in Cardiff to review and discuss Inside Out, an exhibition celebrating the work of illustrator Quentin Blake.

What would your memories of Roald Dahl be without the images of Quentin Blake? With the possible exception of Sidney Paget’s Sherlock Holmes illustrations in the Strand magazine, which, more than Conan-Doyle’s prose cemented a physical image of the great detective in the minds of millions, Bake’s utterly distinctive, scratchy, piratical, anarchic artwork gave a visual atmosphere to Dahl’s dark children’s stories. They are the perfect partnership, and a global phenomenon.

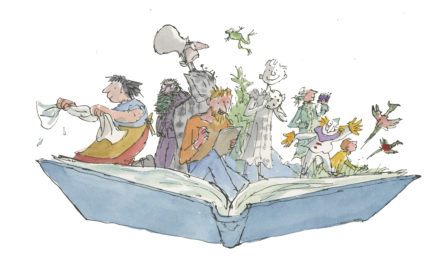

So no celebration of Dahl would be correct without a serious retrospective of Blake’s work, and the one assembled at Cardiff Museum over the next few months is about as good as it could be; a thoughtful, playful, evocative, immersive experience, that has Quentin Blake with you every step of the way. This is not an arms length exhibition; it has in it not just a display Blake’s own personal favourite works, but it is a dissection of his process, his decision-making, his philosophy, his craft. The essence of Dahl’s work, and so Blake’s too – the thing that means the books are treasured by adults as well as children – is laid open here. One corner is given over to the artwork of visitors, sketches on coloured paper imitating Blake’s illustrations (all of them Dahl characters); but it is not just the preserve of children. One would-be artist even marks his name as 35 and a half. Dahl and Blake tap into something very special, once encountered as a child, they challenge you throughout your life to never relinquish the mischievousness that their work instills in the reader.

So no celebration of Dahl would be correct without a serious retrospective of Blake’s work, and the one assembled at Cardiff Museum over the next few months is about as good as it could be; a thoughtful, playful, evocative, immersive experience, that has Quentin Blake with you every step of the way. This is not an arms length exhibition; it has in it not just a display Blake’s own personal favourite works, but it is a dissection of his process, his decision-making, his philosophy, his craft. The essence of Dahl’s work, and so Blake’s too – the thing that means the books are treasured by adults as well as children – is laid open here. One corner is given over to the artwork of visitors, sketches on coloured paper imitating Blake’s illustrations (all of them Dahl characters); but it is not just the preserve of children. One would-be artist even marks his name as 35 and a half. Dahl and Blake tap into something very special, once encountered as a child, they challenge you throughout your life to never relinquish the mischievousness that their work instills in the reader.

Matilda seems to have been a book that was particularly treasured by author, illustrator and readers alike. Here we see the working notes, the stages in progress, and the beautiful, subtle craftwork as, in one example, Mrs Trunchball launches Amanda Thripp through the air having swung her by her pigtails. So from the off we are reminded of Blake’s remarkable talent for kinetic scenes, how his work propels the viewer on with their imagination, but also how he revels in cartoonish savagery and cruelty. You can see what attracted him to Dahl’s writing.

There is a workshop atmosphere to the space. Rare opportunities to see storyboarding are everywhere, as well as unfinished drafts, different efforts in the design of the BFG’s ears, the BFG’s cloak, and the Twits’ unkempt hair.

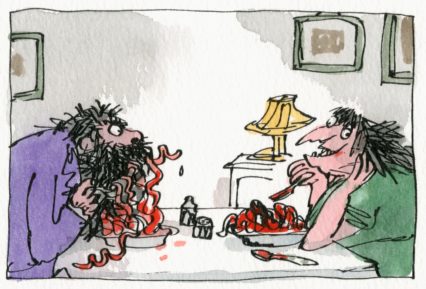

Blake’s words are all about too, very much his wise words, introducing the work thematically corralled. Of his 1974 illustrations for Russell Hoban’s How Tom Beat Captain Najork and His Hired Sportsmen Blake writes, “I think of Captain Najork as a fable about education.” Of the thrilling wall that holds The Twits illustrations he writes, “It’s enjoyable to draw dirty and disgusting people.” And all the way there are joyous insights, but not just to composition, but to the feel of Blake’s work: “Most frequently I draw with a scratchy pen which I dip into a pot of Indian ink. This time [for The Twits] I chose a harder and scratchier nib.” You can see Mrs Twit get meaner.

And if Matilda, that precocious hero child, is a favourite of the artist, it is perhaps the Twits that bring out his most pure work. Blake is always at his best, his scratchiest if you like, when you imagine him over the lightbox going at it with a devilish grin.

Other highlights include Blake’s 2011 illustration of Voltaire’s Candide, perhaps a departure for him in some senses, but then again perhaps not. The classic philosophical tales seem to really tap in to artists of this type – think of Martin Rowson’s explosive take on Gulliver, or Ralph Steadman’s Through the Looking Glass. They seem to be Blake’s spiritual kin in more ways than just the way they attack the paper. In Candide, Blake’s figures are still unmistakably his, swiftly cut from the page and brought to life, but here are new, almost enthusing, thematic elements. The scene after the earthquake where Candide comes upon the now blinded Pangloss has a hitherto unseen dystopic fire to its backdrop. If Voltaire wrote Candide as a response to Liebniz’s famous maxim that this was the best of all possible worlds, it seems Blake disagrees just as much as Voltaire did. They are fabulous illustrations.

Other highlights include Blake’s 2011 illustration of Voltaire’s Candide, perhaps a departure for him in some senses, but then again perhaps not. The classic philosophical tales seem to really tap in to artists of this type – think of Martin Rowson’s explosive take on Gulliver, or Ralph Steadman’s Through the Looking Glass. They seem to be Blake’s spiritual kin in more ways than just the way they attack the paper. In Candide, Blake’s figures are still unmistakably his, swiftly cut from the page and brought to life, but here are new, almost enthusing, thematic elements. The scene after the earthquake where Candide comes upon the now blinded Pangloss has a hitherto unseen dystopic fire to its backdrop. If Voltaire wrote Candide as a response to Liebniz’s famous maxim that this was the best of all possible worlds, it seems Blake disagrees just as much as Voltaire did. They are fabulous illustrations.

And, thankfully, a great deal of space is given to the images Quentin Blake created for Michael Rosen’s Sad Book (2004), here displayed with image and words side by side. How else could they be? It is a deeply moving experience to go along with them, an astonishing connection between two forms of expression of the most heart-rending of subjects – the grief process after Rosen lost his son unexpectedly to meningitis in 1999.

So this exhibition is not just about “illustrating Roald Dahl”. Quentin Blake attaches himself to work that speaks his language, and perhaps Dahl spoke it most fluently, but there are many other treasures to seek out, particularly if it is only the Dahl work you are familiar with. Every step is a delight, a pang, a lump in the throat. And the artistry on display is of the very highest, and most original, of calibres. This exhibition is a rare thing then: unmissable.

Quentin Blake – Inside Stories is on at the National Museum Cardiff until November 20th.

(Images used with kind permission)

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.