Getting close to Joyce can feel difficult. A complex network of academic scaffolding has been built around his work. And though the scaffolding has been erected to support and bolster the building, to the uninitiated it can seem like the front doors and windows are blocked off—and unless you’re willing to scale this pipe and shimmy down that one, you’ll never gain entry to the house.

I don’t mean to do disservice to the incredible—and occasionally insane—commitment of individual academics. But there is something seriously off-putting about approaching a slim book like Dubliners when beside it on the library shelf sits a further hundred books, many of them big books, and all purporting to be about the very same slim book you were thinking of picking up.

Another simile: it’s like trying to talk to a friend in a noisy bar, where the assembled throng are all shouting about your friend, telling you how to understand what your pal is saying, and explaining to you the historical and cultural backdrop of their upbringing, placing this here conversation in the context of past and future ones. In the end—or, more precisely, before you even start reading the stories—you begin to doubt yourself. Indeed, your own experiences suddenly count for very little. After all, you probably don’t have a PhD in Joyce, so how could your understanding of his work ever be as correct or incisive as that academic who has sat in a darkened room for the last thirty years, subsisting solely on plates of peas and copies of Joyce’s shopping lists?

Okay, I’m overstating the case.

But here’s a quick anecdote: I was recently in a bookshop, talking to the very smart lady who works there. She told me how much she loved reading Charles Dickens. And in a conversational hop, skip and jump, we got talking about Dubliners. Very suddenly, her face took on a pained expression, and in a quiet voice, almost a whisper, she said, ‘I know it’s really bad, but I’ve never read Dubliners. That’s really bad, isn’t it? I just don’t think I’d understand it.’

Granted, we can’t lay the blame solely at the front door of my crudely drawn academics. The perception of Joyce as a difficult read is very much shaped by the fact that he also wrote Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. But still, there’s something tremulous about approaching a text where so much has been said about it. Reading Joyce is like meeting an A-list celebrity: how do you get past everything you’ve heard?

*

To celebrate the centenary of the publication of Dubliners, I asked Irish authors to write ‘cover versions’ of James Joyce’s stories. The ‘covering’ metaphor was somewhat nebulous, but, essentially, I asked them to re-imagine the stories in any way they saw fit, to sing Joyce’s stories in their own voices. And for some bizarre reason, the authors said yes. The result is Dubliners 100, a collection of fifteen brand new works of fiction, each bearing the same name as the original tales (e.g. ‘The Sisters’ by Patrick McCabe; ‘Ivy Day in the Committee Room’ by Eimear McBride, etc.) The reception to the collection, so far, has been mostly positive. And with the exception of the one man on Twitter who tweeted, ‘F*** off, write your own stories’, no one seems too annoyed by the idea of contemporary Irish writers meddling with Joyce’s legacy.

Naturally, each author signed up to the project for slightly different reasons. Donal Ryan, who covered ‘Eveline’, saw the challenge as an opportunity to pay homage to a writer that, for many years, had ‘put [him] off’ writing. ‘I was hamstrung by Joyce,’ he said in a recent radio interview. Ryan described the project as ‘an extremely daunting task and one you’re better off not thinking about too much.’ For Eimear McBride, a professed Joyce fan, covering ‘Ivy Day In The Committee Room’ was a chance to ‘have some fun’, in the ‘spirit of the man himself’. To McBride’s mind, it helped that she didn’t feel a strong connection with the original story. As she explained in an interview at Borris Literary Festival in County Carlow, the lack of attachment freed her to take the story wherever she liked.

In his new version of ‘Eveline’, Ryan transposes the genders: the protagonist, Evelyn, is now a man. Evelyn falls in love with an asylum seeker named Hope, but cowed by his ailing, widowed mother, he is too fearful to seize the moment when it matters most. McBride’s ‘Ivy Day’, meanwhile, isn’t as overtly political as the original. In an interview with Totally Dublin, she said she wasn’t ‘interested in writing a figurative story about politics’, and she ‘wasn’t interested in having a go at one figure and one party in particular’; rather, she ‘was trying to capture or show something of the multilayered disappointment of the nation.’ Her take on ‘Ivy Day’ is a Joycean freestyle jazz piece, riffing linguistically off some of Joyce’s original phrasing:

Lately they came in from night, lustrous as dead dogs on the turn. As fat with air and cinder-eyed. Jack, alone, bony in the injudicious light of a long unserviced flame. Patched pimply since life’s handiwork undid, Mr O’Connor rolls himself a cigarette, makes a cylinder of some lot’s gawdy pamphlet, lights, and sets it all a go.

Reading both of these cover versions, one returns to the originals with a distinct sense of the uncanny and a host of usefully problematic questions. In writing away from the originals, the authors have zoomed in close to the source, and have brought the reader along with them. After encountering Donal Ryan’s browbeaten Evelyn, I couldn’t be sure if Joyce’s Eveline leads a life as circumscribed as she imagines, or whether, perhaps, she is bound by her own sense of fear. (The answer is probably neither, or a combination of both, or something in between; complication is ever the way to verisimilitude.) As for Joyce’s ‘Ivy Day’, I was struck, upon re-reading its final lines, by the characters’ sense of hope and what McBride described in an interview as their ‘fine feelings’—feelings she thinks that are quite impossible to have in today’s political climate:

The level of discourse, and political discourse, has been lowered so greatly […] No one dare ask more of themselves, or of anyone else, or take things seriously in that way.

For some contributors, however, the cover versions were borne of a deep connection with the source material. When I approached Paul Murray to contribute a story, he replied, ‘You’re not going to believe this, but I’ve already done it…’ and he pointed me towards a story of his called ‘Saint Silence’ which he had published in Five Dials in 2011. When reading Dubliners at university, ‘A Painful Case’ had resonated with Murray, and he set about recasting the story in contemporary Dublin, with the protagonist of the original becoming a brutal food critic, renowned for his abrasiveness:

‘For mains, I ordered the steak tartare,’ he wrote of Rumpole’s. ‘However, the waiter must have misheard me, and thought I asked for a giant pus-filled herpes on a plate.’

‘Is there such a thing as a chicken Auschwitz?’

As Murray explained in an as-yet unpublished interview with Gillian Moore, ‘I really responded to that kind of severe mentality that James Duffy has, he’s a very judgmental kind of a character, very angry and isolated.’ Building an intricate web of layers and connections from images and ideas in the original story, Murray’s ‘A Painful Case’ charts and dramatizes—through the prism of Nietzschean ideals of masculinity—the homoerotic undertones inherent in Joyce’s James Duffy. If all that sounds a bit academic, just reading the two stories side by side is enough.

It didn’t surprise me that Murray had already ‘covered’ Joyce. To return to my overblown books-as-building metaphor: sometimes an author needs to don someone else’s clothes to sneak into houses they mightn’t usually get to enter. Once inside, they can cast off the borrowed garb and decorate the rooms to their own taste. Indeed, Joseph O’Connor, in an essay I would like to quote from (but probably shouldn’t, because this very recent and very excellent essay by Andrew Fox about his own cover version of ‘After The Race’ already quotes from it) explains how he—Joseph O’Connor—learned to write fiction by literally typing out stories by John McGahern. Of course, I’m not telling you anything new here. ‘Imitation as gateway’ is already a well-worn forest path with familiar scenery: there, to your left, naked in a tree, is Blake deliberately misunderstanding Milton; there, to your right, is Shakespeare reading the Greeks by candlelight; and there in the foreground, his mouth a bitter gnarl, is Harold Bloom talking authoritatively about it all. But influence and legacy can be a hindrance. Especially when you’re Irish, and especially when it’s Joyce.

After Tramp Press announced they were publishing Dubliners 100, the Irish Times ran a piece with the headline ‘Irish authors step out of James Joyce’s shadow to take on Dubliners‘. Immediately, then, the authors were portrayed as earnest scribblers who’ve been living under the monolithic spectre of Joyce, devoid of light, and itching to finally pit themselves again the Big Man. This perception of the relationship between Irish writers and Joyce was something I was warned about by an author who declined my invitation to contribute a story. In a superb email, which I now have framed above my bed, this author told me that the project was an ‘odd idea, a bad idea’. As an Irish writer, they said, they were forever casting themselves in relation to Joyce. Critics asked them to comment on Joyce, to respond to Joyce, to confess of Joyce’s influence. The reading habits of this insulated cadre were lazy and complacent, the email read. A project liked Dubliners 100 only played into the critics’ hands.

It’s a compelling point, and one I understood and very nearly agreed with. The argument put me in mind of the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie who I once heard bemoan the tendency for critics to incessantly ask her about Chinua Achebe. Indeed, for many Irish writers, it must sometimes feel as if they are constantly in the State-of-Gabriel: looking out the window, staring at the snow, while someone harps on about a dead man who was really, really great. But I don’t think the solution lies in avoiding Joyce. As Julian Gough puts it, in his provocative essay on Joyce for Prospect, ‘you can’t ignore the bastard’.

Indeed, some things I learned editing Dubliners 100:

1)

Even in Dubliners, even before he wrote ‘The Dead’, Joyce was an absolute master of indirect free speech. Elske Rahill, who covered ‘A Mother’ for the anthology, says she spent a long time closely reading the original to unravel the many threads of voices in the story. Dubliners is often praised for the way Joyce doesn’t explicitly judge his characters, but in ‘A Mother’ it’s evident how deftly Joyce can inflect a sentence with a cool ironic light:

The first part of the concert was very successful except for Madam Glynn’s item. The poor lady sang Killarney in a bodiless gasping voice with all the old-fashioned mannerisms of intonation and pronunciation which she believed lent elegance to her singing.

It’s not always easy to pin down who’s doing the judging, but the above clearly possesses an aural quality, a quality of a story being recounted. You can almost hear the italics on ‘very’, ‘poor’ and ‘she’.

2)

Every time the Rhys Davies Short Story Competition comes around, I look at the 2,500 word-limit and think, how the hell am I meant to get a story up and down in that short a space? Yet, Joyce’s ‘Araby’ is only 2328 words long; ‘Eveline’ is 1827 words, ‘Clay’ 2635 words. Joyce’s self-professed ‘scrupulous meanness’ wasn’t an idle boast.

John Boyne, in writing his cover of ‘Araby’—a story he describes as Joyce’s ‘heartfelt memory of being young and confused by first love’—set himself the challenge of writing his version with the exact same word-count. Even when plotting it according to the same graph as the original, Boyne’s first draft came in at around 4000 words. It took some scrupulous cutting to bring it down to match the original.

3)

Reading ‘Counterparts’, it’s startling how powerful Joyce’s understanding of alcoholism actually is. Farrington, the office clerk, knows he has work to do, but he can’t tear himself away from the itching thought of the pub. Seventy-five years later, the Scottish author Ron Butlin wrote the majestic novel The Sound of My Voice, about a manager at a biscuit factory, who knows he has work to do, but he can’t tear himself away from itching thought of the pub. And then we have Belinda McKeon’s Dubliners 100 version of ‘Counterparts’, about an arts administrator, who knows she has work to do, but she can’t tear herself away from the itching thought of the internet. In all three works, it’s the vicious, downward spiral that’s so difficult to watch. When the perceived solution to the problem is actually the root/propagator of the problem itself, that’s when you’re in trouble. Joyce understood this, and his insights on addiction remain illuminating.

4) It’s absolutely ridiculous that Joyce was only twenty-three when he wrote most of the stories.

I’ve nothing to add to that.

*

There is, I feel, a growing unease with Joyce’s prominence in the domain of the Irish short story. In a recent discussion on ‘The Art of the Short Story’ at the Dublin Writers’ Festival, the novelist and short-story writer Mike McCormack criticized what he perceives as stasis in the form. In his view, the Joycean-Chekhovian model—the single-voiced, past-tense story leading to a comma-laden epiphany—is very much still dominant. For many Irish readers and critics, he argued, if a short story hasn’t done the above, then it hasn’t done its job. Where’s my epiphany? they cry.

Regardless of whether McCormack’s argument is true—and 1) I think he has a point, but I’m not sure how you would go about proving such a thesis; and 2) it should be noted that Joyce’s ‘The Boarding House’ is told from three points of view—it is certainly an attitude I’ve heard many other writers express. Indeed, Joyce’s reach even goes beyond form, all the way down to the level of the sentence. As Anne Enright recently joked—and Eimear McBride added to here—the closing sequence of ‘The Dead’ is perhaps almost single-handedly at fault for more bad writing than any other short story.

There comes a time for many Irish writers, then, to confront Joyce. Even if he’s not a writer stocked in their literary fridge, at some point someone is going to draw a connection or make a comparison. And subsequently, the writer will find herself stuck in a binary bind: her work is either seen as working towards Joyce or as a deliberate departure from his work. But, in truth, this is the case for any book that a writer reads. When reading someone else, a writer will inevitably compare themselves to the work in hand, and—even if it’s only subconsciously—they will ask: what can I steal from this? Where are the limitations? As Patrick McCabe explained at Borris Festival last week: his early work was an imitation of Frank O’Connor—until he read Richard Brautigan. Brautigan, he felt, captured an essential element of how life was being lived: namely, that we were entering the Visual Age. And this rejecting and accepting, this pushing and pulling, is how so many writers operate. Ben Yagoda’s hugely illuminating study The Sound on the Page is a convincing argument for this: a writer reads other writers for style; they’ll take what they need and discard the rest.

*

When interviewed about Dubliners 100, many of the contributors have been asked if they felt ‘daunted’ by the task, and the truth is the vast majority have replied, ‘no’. (Though I should state that one author turned down the invitation to write a story, stating that Joyce’s works are ‘sacred texts’.) But for most of the contributors to the anthology, Joyce is an important writer, but he is just one amongst countless others who have figured in their literary apprenticeship—one author among hundreds from whom they’ve borrowed/stolen. Belinda McKeon was recently asked if to re-write ‘Counterparts’, ‘she had to break up all the frozen admiration that attends Joyce’s work?’ Her response, I think, is typical of many of the other contributors, and also a telling description of the mental environment in which a writer sets down to work:

I don’t know if I have a frozen adoration of Joyce, actually. Which is not to say I don’t marvel at his work—I do—but every new story owes a debt of one kind of another to an old story, consciously or unconsciously, so in a sense this invitation was not hugely different to the starting-point of any new piece of fiction.

Meanwhile, for Peter Murphy—the author who covered ‘The Dead’—stories by Flannery O’Connor and Ray Bradbury have been more influential than those written by Joyce. Murphy says he saw the opportunity to cover ‘The Dead’ as less about homage, and more about the chance to have fun with a canonical text. His version, set in a post-apocalyptic Ireland, offers language and a backdrop somewhat different to the original:

Straight off I reckernised their sort as the class of jackdaw folk what got by collecting scrap and bartering it to the any-old-iron man, or what brought recyclables to the mobile mart for to be traded in exchange for cans of brew. Clouds of glowing ash rose from the fire and settled in their hair like bits of burning snow, but they did not seem to notice or to mind – fate it was as though they had no nerves at all.

In Murphy’s view, Joyce’s work isn’t a burden. Rather, Dubliners is a pool to dive into—and occasionally draw from. Writing his second novel, Shall We Gather At The River, Murphy realized he had unintentionally re-written Joyce’s ‘An Encounter’ into a key scene in the novel. But such has always been the way with writers: they read, they digest, and they create. And once they’ve passed the Imitation Stage, influence casts a light, not a shadow. When BBC Arts Extra asked Murphy how Joyce—were he alive—would respond to the Dubliners 100 project, his response was deliciously droll: ‘I don’t know if Joyce would be offended, I never met the man.’

*

Writers aren’t always the most thorough of critics. They have their own concerns and they see these concerns everywhere, especially in other people’s work. And when discussing other writers, the writer hopes—I think—to avoid the rigorous examination that an academic gives to an author, and instead, prefers to skip above it all by attempting to capture some essential spirit of the work. Or, to misquote Chekhov; the writer isn’t someone who aims to provide answers or solutions, but rather, she seeks to pose the difficult questions. To deepen the mystery, as it were. It’s my hope—and belief—that the authors contributing to Dubliners 100 have done exactly this.

In asking writers to ‘cover’ Joyce, I was asking them to think of the stories as individual songs, and thus take them apart and reassemble them as such. What’s the melody of a story—is it its theme? What about the chorus? How do the drums sound in ‘Grace’? What are the key lyrics in ‘Clay’? And where does character fit into all this? How important is setting? (Two of the cover versions actually concern Dublin emigrants in New York.) Rather than asking writers to merely modernize the original stories, I was asking them to isolate the parts they saw as crucial and to recast the story accordingly. And magically, this is what they’ve all done. They’ve given us brand new stories. But also, in multifarious and wholly inventive ways, they’ve given us distance from the original stories, distance that allows us to see Joyce’s Dubliners afresh. In this regard, the work undertaken by the contributors is akin to that of the psychoanalyst. They haven’t sought to cure or put immediate ease to a problem; but rather their works are probing prompts that allow the reader to navigate the original stories—not with fear or with the heavy weight of learning—but with that number one Essential Reading License: curiosity.

For me, the most telling moments in Dubliners are the ones that give the tingling pleasures, the ones that seem to zone in on something wholly real and wholly true, the ones that make you feel but also make you understand something that can only be communicated through the story, that can only be found when you inhabit Joyce’s actual sentences. You don’t need to read an academic study to encounter these things, and you certainly don’t need to hear the cover versions to grasp these human truths. But if it has been a while, I urge you to go back to the original source, to re-read Dubliners. Forget all the half-learned, half-heard things you think you’re meant to know about the stories, about Joyce, and maybe even forget the things Joyce himself said about the book: its themes of ‘paralysis’, the ‘scrupulous meanness’, and the collection as a ‘well-polished looking glass’. Just forget all that, and enter as you would an engaging conversation, late at night, drunk off your head, with some curious person who seems to understand you better than yourself. Tune out and ignore the other voices. Delve deep, and get in close.

*

Thomas Morris is from Caerphilly, South Wales. In 2005 he moved to Dublin, where he now edits The Stinging Fly. His debut short-story collection, We Don’t Know What We’re Doing, will be published by Faber and Faber (Summer 2015).

Dubliners 100, edited and devised by Thomas Morris, is available from www.tramp.ie

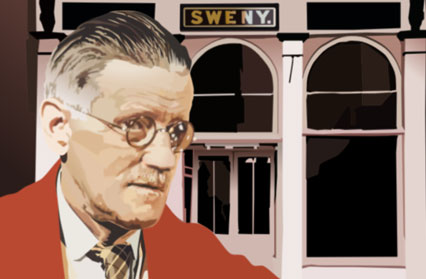

Illustration by Dean Lewis