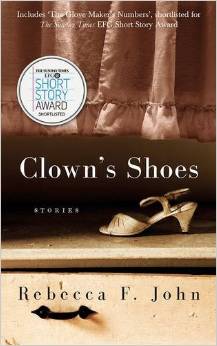

Zoe Ranson casts a critical eye over Clown’s Shoes, the debut short story collection from Rebecca F. John.

Autumn: damp days and waning light; a bite to the air and snapping underfoot. And though darkness presses in earlier, we witness the world at its most dazzling: trees resplendent, about to bare all. It’s a fitting time for this debut collection from critically-acclaimed short story writer Rebecca F. John to emerge. A damp, chilly vein runs through its spine with splashes of warm earthy colour.

What’s exciting is that through John’s lens we get that these are lives we are witnessing, not styles, not garbs thrown on for a weekend slumming it, part-time punks. There is no normalcy to return to, and these are lives of the forgotten, the overlooked, downtrodden and regretful. That writerly grail, the simultaneity of the self is mined, showing how it is possible to be (and feel) two different contrasting things at once.

John favours a searchlight on the lonely and forsaken. We peer into worlds containing lives so brittle you should be afraid to touch in case they snap or wither. There is a timeless, sensual quality to John’s prose and a creeping seam of unease underpinning these sketched lives. ‘The Dog Track’ snaps and springs to life, the eerie twilight worlds of striptease and Jazz clubs emerge through tender prose that renders images so vivid they strike and keep on striking in the darkness that follows.

Assembled together, the overarching tone is sombre: these are lives that echo bleakness. They range in geography, but the mood prevails. The tenacity that characterises courageous humans under duress but making it work, these pictures form an unrelenting voyage into the modern human condition, with only the occasional splash of colour, from the universal canopy of the sky.

Interestingly, stories in the first person are rare (just two out of the sixteen collected here – both in vernacular) and, without exception, light on dialogue. The author is entirely absent, choosing instead to move spotlight between her cast.

The third person is favoured for the flexible approach to point of view, relied upon in a number of these stories, employed most painfully in ‘Her Last Show’ where the gaze follows first inept mother, then teenage daughter forced prematurely into responsibility which curtails her childhood.

The opening story, ‘English Lessons’, begins with the sense of displacement and misunderstanding that is the major artery through the whole collection. The journey of a twelve year-old girl, Eunkyung, is told in non-linear sections, beginning in her Post-Christmas present, hiding in the rocks, interspersed with sections that provide the backstory to her arrival from Korea into a foreign world – a new life – with her aunty and uncle in, not London, England, as she first believes, but Wales. Eunkyung’s confusion at times bleeds into the point of view. The childish voice is sometimes preternaturally old for someone who ‘never even started Middle School’. Like this comprehension:

Cardiff was smaller than Eunkyung had imagined: the streets were short; the buildings stubby. Compared to Seoul, it looked like a toddling child.

In the Sunday Times EFG shortlisted story, the quiet agony of the unusual protagonist, Christina, radiates as she counts and waits, through moments of beauty: ‘Sleep and all its happy lies’ and humour: ‘Because the Devil visited me, and it was very unfortunate.’

Christina wants to transcend the personality of her inmates. So she thinks of them

…not as names but as figures. Figures who do not have families or pasts. Figures who do not know pain.

This is an irony, as John’s affinity is with writing characters just the inverse. These are a collection of figures who both know pain, and feel it deeply. Misfits compelled to seek shelter and solace in the underbelly who can only imagine themselves a different existence. Their sombre moods evolve and are elevated through elemental description. Dialogue is sparse and skies are plentiful. In ‘Bullet Catch’,

…lacing strips of scarlet and lavender into the pearly clouds. The ancient stone was the colour of candlelight in the city dusk.

In ‘Salting Home’, which presents one of the most complex emotional profiles in the ensemble, a mother remembering her absent daughter recalls: ‘Everything was bleached and cold and they could breath ghosts into the sky.’

A characteristic of John’s prose is the unusual choice of verb (‘a rabble of black butterflies’) – a stylistic trick that will inspire wonder in some readers, but one which I, at times, found jarring, rather than poetic. It can chime wonderfully. The ‘accidental wife’ who narrates ‘The Dog Track’ alights on: ‘He was a storm, my brother; the eye and the messy aftermath.’ And in other instances, the images don’t quite hit. In ‘Her Last Show’ a chandelier ‘its base a confusion of carved white mermaids.’ But overall the tone of this story, a spinning human zoetrope of mother, daughter and son, wrenches, as you see the permanently peripatetic lifestyle, echoing sadness through the generations. Rosa without willing it has inherited her mother’s lot:

She would put her beauty to much better use than her mother ever had. She would use it to hurt people, not to make them love her.

If these stories are united loosely, it is apparent in the tropes of the Big Top. The Circus is a world that embraces freaks and drop-outs, finds an environment for misfits and physical or mental deformity to survive. But despite allusions in the titles ‘Live like Wolves’, ‘Bullet Catch’, and, of course, ‘Clown’s Shoes’, John’s Big Top is not in the magical realm of Angela Carter, the grotesque-beautiful sideshow of Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love, nor the anthropomorphology of Karen Russell. There are no talking animals, or showy acrobatics. Instead we linger in the shivery shadows of a world of John’s own creation, with the sense of kicking over a rock and examining what lies beneath. And like the circus, a creature many-faced and perpetually on the move, we don’t stay too long in one place.

The longest of these dalliances, at the centre of the book, is ‘The Bird Wall’; depicting a shell-shocked, lonely pensioner in alliance with his young next door neighbour (a set-up like ‘The Selfish Giant’). Increasingly confused, he mistakes his young neighbour for his lost farmhand. It is this story that cuts the deepest. It marauds sentiment, but strikes a baser note before it’s in danger of becoming saccharin. Crows (along with the sky, a recurring trope) appear to tap dance an ‘intricate series of slow motion steps and hops, sometimes extending its wings, sometimes pleating them away.’

A tentative shunt into William Trevor territory (reminiscent of ‘Timothy’s Birthday’) without his plangent oddness, is the quietly devastating ‘Moon Dog’; a slow reveal of regret in a family drawn apart and lost for words, words found only when the gulf between parent and child is too broad to be gulfed and the sense that distance between them will only deepen and coarsen over time. The subtle interplay between father and son, and husband and wife belies lives forsaken through disappointment, expectations pitched too high to have been satisfied with what is.

Rather than a jaunty Circus overture, the tempo is doloroso. Even the sky is angry in the end. This is a dark, damp and claustrophobic world, infused with ‘the blue colour of trouble’. Push your face up to the keyhole and take a look inside.

Clown’s Shoes is available from Parthian Books.

Zoe Ranson is a writer, actor and contributor to Wales Arts Review.