Maja Palser interviews Charlie Barber, a Cardiff-based composer, who has worked extensively in a wide variety of musical genres about his work and influences.

Charlie Barber is a Cardiff-based composer who is hard to pigeonhole. He has worked extensively in a wide variety of musical genres and across a number of different art forms, from music theatre, dance, film and video, to installation and performance art. Working collaboratively with artists in other disciplines, he has a deserved reputation for creating and producing innovative performance projects. His latest project, Michelangelo Drawing Blood, toured the UK with his production company Sound Affairs to great acclaim earlier this year. Charlie spoke with Maja Palser about his work and influences, and what drew him to becoming a composer.

photo by Matthew Thistlewood

Maja Palser: You have an extensive track record of productions that combine new music with various other art forms, ranging from dance, performance art, theatre, film, installation art and painting spanning almost four decades… As a composer, how vital are extra-musical factors and ideas in your work?

Charlie Barber: They’re not vital, but they are sometimes helpful. I’ve often believed in that John Cage and Merce Cunningham idea of two art forms running together in parallel, so one art form isn’t dependent on the other supporting it. That’s informed a lot of my work, whether it’s with music and film, music and theatre, music and dance, or so on. I didn’t want to write something that was underscoring, or subservient to, another art form.

Unlike the majority of ‘classical’ composers, your background is not academic. Could you tell me a bit about your early career and how it came about?

When I was a teenager, my school music teacher arranged for me to have composition lessons with David Wynne. I used to come across every week from Newport to the Welsh College, which was then at Cardiff Castle. When I left school at seventeen I was torn between having a career as a composer and studying theatre design. I went to art college for a few days and decided it wasn’t right for me. Then I went on to work with a variety of bands. I was doing a rock programme which was heavily influenced by David Bowie, and I was interested in Bertolt Brecht and the French author Jean Genet. I’d already written some incidental music for theatre, as well as other compositions, and the then director of the Sherman Theatre, Geoffrey Axworthy, asked me to work with Agnes Bernelle, who was a cabaret singer of the Lotte Lenya mould. Subsequently I worked with a few theatre companies in Cardiff doing theatre in Wales. Around the same time as the Bernelle programme, Phil Thomas asked me to work on another Brecht/ Weill music theatre piece, Die Kleine Mahagonny. Out of that I met some musicians who wanted to set up a contemporary music group and we formed The New Arts Consort that went on for about ten years. Then I formed Sound Affairs as a production company.

You mentioned John Cage as an inspiration. Who, or what else would you say were your earliest influences?

When I was very young I was a huge opera fan. I think the first one I saw was Wagner’s Tannhäuser, I must have been eight or nine or something. The earliest influence I had in my mid teens was Alban Berg. I remember coming to see the WNO production of Lulu at that time. The other person I was particularly interested in was Hans Werner Henze, and through Brecht, Kurt Weill. So in terms of the transition between writing music from a theatrical pop/ David Bowie perspective into German Expressionism, the music of Weill, the plays of Brecht, and the films of Fritz Lang and co – that was the transition of one area of working into another I suppose.

Presumably then it was your background in theatre, along with your early interest in opera that were the main factors that attracted you to writing music for the stage.

I was interested in opera early on, but I then began playing in a blues band, then a soul band, and various other outfits. When I saw David Bowie’s 1973 tour I suddenly realised that popular music could actually be theatre. And, obviously I had this interest in theatre design. So I used to do a show which was influenced by Brechtian theatre in that there would be slide projections going through the performance. After that I was invited by other theatre companies to work with them.

On your website you tend to describe your stage works as ‘Multimedia events’, ‘Music Theatre’ and ‘Theatre Cabaret’; there’s a sense of the more anarchic, smaller-scale cabaret style of music theatre, rather than the polished operatic style. Would you say there has been a tendency towards the anti-opera in your works for the stage?

Having been wildly enthusiastic about opera as a teenager, during my twenties there was a cooling off period. It wasn’t particularly to do with the art form itself or the content, but with the political and economic aspect of producing opera; obviously it takes an enormous amount of financial resources, which some people might argue could be spent in other areas. I wouldn’t have used the term ‘opera’ to describe anything that I was writing. The only thing that could fit that was the recent Michelangelo Drawing Blood piece, which I did think of in some sense as a chamber opera, albeit it was for solo countertenor. But it was decided not to call Michelangelo a chamber opera because the word ‘opera’ might put some potential audiences off.

Did that factor also play a part in your earlier pieces? When you had your cooling-off period, was that how opera was perceived generally by your potential audiences?

No, not particularly. Although I think sometimes terminology can be problematic. I went through a phase, and I’m still partially in it, when I didn’t like the term ‘contemporary music’ and I would always describe it as ‘new music’. I felt that, in some people’s minds, ‘contemporary music’ would mean things like Peter Maxwell Davies or whatever. Whereas people who were working with a broader view of things, a larger pallet, I think would be more inclined to be described as ‘new music’. But then, with the explosion of Indie bands, they often called their stuff ‘contemporary music’ or ‘new music’, so in terms of potential audiences there was a huge amount of confusion as to what somebody meant by ‘contemporary music’ – did they mean Oasis, or did they mean Peter Maxwell Davies? And pretty much ditto with ‘new music’.

A strong influence that carries through your work is world music, and traditional art forms from different cultures.

I suspect that is partly because I didn’t have this formal music education and partly because I was interested in newer forms of music-making that weren’t just tied to the contemporary classical music tradition of Darmstadt and so on; I was interested in other musics, particularly African music – bands like Kundu Boys. I was intrigued by the rhythms of African drumming and wanted to find out how all that happened, how it evolved, and what was going on in those rhythms. At some point, I don’t quite know when, I got interested in Indonesian Gamelan music.

You did a piece for that…

Yes, for the Gamelan group based at St. Davids Hall. But I had an interest long before that. I think the reason is that the Gamelan is one of the earliest forms of orchestral music – that is, a large group of musicians coming together to perform music. And it’s not improvised, it’s all learned. Again, I was interested in how the thing is put together. The structure from all these different genres of music was the thing that fascinated me. And similarly later on, Indian music and the Raga system, and Arabic music – again because of the rhythms and time signatures. All of them are just completely different to the way that Western music has evolved.

In 1979, you composed an ‘opera’, Friends in Arms in the style of Japanese Noh theatre. The story meanwhile was based on the legend of Achilles… An interesting combination!

That was with James Kirkup. I don’t know who suggested the subject of the Trojan War – it might have come from him. The interesting thing was that in Noh theatre quite often the principal actor will take two different roles in the two different halves of the piece. In Noh ghost stories, we often get the ghost in one half, and a different person that is somehow connected in the other half. I think the principal character might have been Achilles in the first half and the ghost of Petroclus in the second half. Although I was interested in Japanese theatre, I didn’t know a great deal about the music that they had either for the Noh theatre or the Kabuki theatre, so I did some research into Japanese music, which was also, I suppose, utilised in 1981 when I did a multimedia performance piece called Punishment by Roses, based on the Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima. There was a particular section of that which musically was based on Noh theatre.

The amalgamation of different musical genres is a characteristic of your work in general. In the Ballet BreakBeats from 2005, for example, you collaborated with DJ Jaffa.

At some point I got interested in hip hop. I quite liked some of the production on some hip hop records, and I really liked two things: one was the beats and the rhythms, and the other was the atmosphere created by the samples that DJs were using; if you took a sample of something, not only did you get the notes and pitches of that particular phrase, but you also got a load of atmosphere from that session. BreakBeats was written for a duo, piano and percussion, with backing tracks to support it, and two break dancers. There were some other DJs that made a contribution to the backing tracks, but DJ Jaffa came on tour and performed live as well.

How did the music actually come about? Did you write things that they performed, or did they bring in their own material which you added to?

A bit of both. There were three DJs involved. There was Jaffa, a collective called Optimas Prime, and DJ Keltech, and some of them provided beats they were working on; each of them gave me a selection and I made a choice from those, to put another layer on top, performed by live musicians.

Would you say there is a sense of wanting to close, or at least minimise the perceived ‘social gap’ between what some would call ‘art’ music and popular genres? Do you see your music to some extent as a means of introducing classical music audiences to popular music and vice versa?

Yes. I’ve never had that notion of boundaries. Some people have this idea that a work or an art form has certain parameters; I just don’t see those ‘walls’ as existing. And I think looking at other types of music and world music just helps to reinforce that: even though they may have evolved in different ways, there do seem to be certain things which are just like basic ‘building blocks’.

Over the past decade you have scored several silent cinema classics. Can you tell me a little bit about what attracted you to this particular art form?

There are a few things. One is that you’re working with something that already exists, that might have been made eighty or ninety years ago. Writing music for a silent film is very different from collaborating with a living film director who might have certain ideas or preconceptions about what they want and how they think it should go. Also, in terms of a touring production, you’ve got something – it might be an epic or a costume drama or a period piece – which is on quite a large scale, with a whole host of actors, chorus members, people in the background and sets; and it’s all been lit. So you don’t have to take those things on tour, which is fantastic!

The other thing is that the production usually features someone that might be a bit of a name. So it’s quite good from a marketing perspective because all sorts of different people and potential audiences might know that person, or that story. The first one I did was Moulin Rouge, and I think there are about five film versions of that, so as a story it is sort of known. Salomé, again, is a story known from the Bible; and Nazimova herself has got quite a reputation and history, so that all counts when you want to do a performance or screening. With regards to Jean Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet, I’d been interested in his work for decades, partly because he dabbled in a lot of different art forms; he wrote plays and poetry, he directed films, he wrote the text for Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex, he did many, many things, paintings and stuff. He also finally managed to get Jean Genet released from prison, so there’s that connection.

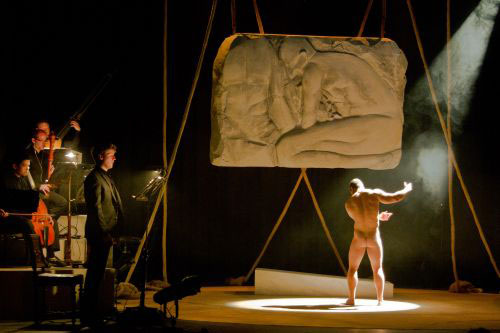

photo by Toby Farrow

From a composition point of view, is it also the absence of dialogue, and the stylised manner of acting in the silent film genre, that is part of the appeal? You could almost describe it as similar to dance or performance art, compared to current cinema that is mostly very realistic.

I think it is part of the general appeal, not particularly as a composer. It’s true from a practical point that you don’t have to make allowances for the dialogue, or worry about it not being heard. And in a lot of the silent films there is an acting style which teeters on the melodramatic. What that means is it’s very expressive in terms of facial expressions but also with gestures; a lot of that is more like physical theatre. Obviously at the time when these silent films were produced, there would often be a piano accompaniment. Sometimes there were larger groups. When I first came across silent films it was the German Expressionist films of Fritz Lang, Pabst and Murnau, this was in the 1970s and most of those were being screened with a sort of electronic score. And then, following on from that, there were some live performances – again with the same sort of repertoire, Nosferatu, or whatever – and it would often be one or two guys with synthesizers. So it was still in the electronic ‘realm’, so to speak, and it tended to be pretty much improvised, whereas I wanted to do something which was composed and used other instruments.

One of your aims is bringing together audiences of early cinema and new music. How effective would you say this format is in making new music more accessible to a wider audience?

I think it is very successful. Even with contemporary cinema, a lot of film music is very popular. You get a lot of orchestral concerts of Star Wars themes, Harry Potter, all of that, and the John Wilson Orchestra which specialises in the Bernard Hermann scores, the Hitchcock scores, that type of thing. So I think those have always been popular. I know quite a few dancers and choreographers who use film music as a starting point for their pieces because I suppose they probably find it easier to work with than some concert music pieces.

Would you say that we are at a point in time where silent movies are beginning to become more popular again?

When we did the second tour of Salomé, in 2011 to 2012, the film The Artist was suddenly very popular. I suspect it won some prizes, and as I understand it, it is silent throughout and is set in that sort of period. Interestingly enough – I don’t know if it’s been released – there was another film being made around that time, which again was a silent film, based on a lot of characters from early cinema, including Nazimova.

So that shows that there is more of a demand for that kind of genre again.

Yes. And it produced its own stars and celebrities, Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, Gloria Swanson… And although they didn’t speak on screen they’ve got enormous reputations, partly because of the performances captured on celluloid, and partly because the first stars of cinema were pretty wild! They didn’t have any role models.

Going back to Michelangelo Drawing Blood, a touring project you completed this summer, it was comparatively large-scale, combining music, performance and film. Would it be fair to say that conceptually this piece was moving away slightly from the rebellious, anarchic feel of many of your earlier stage works?

One of the things that attracted me to it was the opportunity to look at, work with, and write for period instruments, which I hadn’t done before. I always think that the research part of a project is one of the most exciting, when you discover new things. Over the last few years I got more interested in writing full-length pieces. That’s partly because I just find it more satisfying. I think a concert performance with different pieces to it is less satisfying, whereas if you’ve got an overall idea of what the single work is and how it goes I think it just presents a stronger case.

Again, Michelangelo is fairly difficult to pigeonhole, even more so perhaps because it is not particularly reminiscent of related art forms such as cabaret or musical theatre. Could you tell me what inspired the work?

I’ve often been interested in that area where you get a tiny part, a fragment of something, and from that you construct something else. With the Michelangelo project there was no way that I myself or the other collaborators wanted to do a story, a documentary of Michelangelo. But there were certain things that I wanted to explore. Some of them were art-related technical things like perspective and so on. I was also interested in some of the early religious music because Michelangelo was such a devout person. It seemed logical to include that aspect in the production. Some of the texts that I used were from the church or religious sources; others were from Michelangelo’s own writings, from the poems or sonnets. On some of his sketches and drawings, because he re-used paper so many times, you’d find odd things like shopping lists, so I thought it would be quite interesting to include a shopping list. So obviously there isn’t a narrative, but I saw it as more dream-like, with unconnected episodes, images and things jostling around for attention. And although they might seem a bit random it would make a certain sort of sense.

You are in the process of creating a virtual archive of your works to date. Will we be able to access any of your earlier material, such as recordings and scores, videos that have so far remained unreleased?

Yes I hope so. There are some recordings – I’ve got some on really old two-inch tape which we’ll have to bake before they can be digitalised, and the baking process might destroy them completely, but we have to take that risk and see if they can be digitally restored. Again, other things will be put online, but it’s just going to be a long process.

What touring projects have you got planned for the coming year?

I’m currently working on a project re-working an earlier silent film with live music, The Fall of the House of Usher. It was initially written for the National Youth Wind Orchestra of Wales and the starting point of the music score was the sketches that Debussy wrote for an uncompleted opera between 1908 and 1917. The film was made by Jean Epstein in 1928. The Wind Orchestra asked me to do a project with them and they wanted to do a film, so I suggested The Fall of the House of Usher. They did it as their annual Easter project in April 2012. Because it’s such a large orchestration – about fifty players – it would be quite difficult to do a touring production of that so I’m looking at doing a reduced version for about twenty players to tour from June 2014 onwards.

photo by Matthew Thistlewood

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis