From cinematic guitar riffs to advert earworms, glorious Welsh choirs to studied silence, a selection of Wales Arts Reviews’ top writers reflect on a particular musical experience which has had a real impact upon them.

Craig Austin

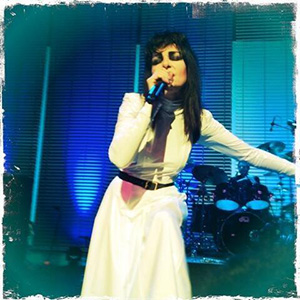

Siouxsie Sioux

I’ve only ever had two heroes. My granddad, for reasons so fundamental to my very being that if I started to recount them I fear I would be unable to stop, and Siouxsie Sioux. With Sioux, my rationale is quite simple. In a world underpinned by soul-sapping compromise and entirely artificial notions of fear and apprehension she has lived a life so completely on her own terms, and with a creative vision unencumbered by anything as gauche or crass as ‘fashion’, that the extent to which she is insufficiently appreciated as a true visionary and artistic pioneer borders on the shameful.

I’ve only ever had two heroes. My granddad, for reasons so fundamental to my very being that if I started to recount them I fear I would be unable to stop, and Siouxsie Sioux. With Sioux, my rationale is quite simple. In a world underpinned by soul-sapping compromise and entirely artificial notions of fear and apprehension she has lived a life so completely on her own terms, and with a creative vision unencumbered by anything as gauche or crass as ‘fashion’, that the extent to which she is insufficiently appreciated as a true visionary and artistic pioneer borders on the shameful.

Her recent revelatory show at the Royal Festival Hall following a period of relative creative dormancy was an occasion so personally significant for me that I spent the best part of the afternoon holed up in the top floor bar of the venue mainlining espresso, whisky, J. G. Ballard (it felt appropriate), and the Banshees’ bafflingly underrated acid-drenched psyche-pop masterpiece, A Kiss In The Dreamhouse. A joyous alchemy of multi-tiered stimulation interrupted only by the dull thud and industrial clang of the embryonic sound-check that was building in increments beyond the heavy wooden doors that sought to contain it.

As muffled and ambiguous as it first presented itself the bewitchingly elegant opening guitar line of ‘Happy House’ sliced through the fug like a ceremonial sword. And for a fleeting moment I was ten years old again, watching in awe as the heavy arm of my archaic hand-me-down record player dropped clumsily down upon the seven inches of black plastic that would forever captivate me. Its blunted stylus eagerly seeking out a vacant groove in which to embed itself, the crackle and hiss of expectation giving way to a magnetic slice of beguiling decadence.

As a child, it acted as an entry point to a world of alternative art that would play its part in defining what felt like my every thought and gesture. As an adult it delivered something even more precious; an utterly thrilling sense, albeit briefly, that anything and everything was once again possible. Everything.

Jim Morphy

Tom Waits, ‘Invitation to the Blues’ and Nicolas Roeg

I had a wonderful week recently watching and writing about the films of Nicolas Roeg. Music is central to the director’s work – for a start, Mick Jagger, David Bowie and Art Garfunkel play three of his lead characters. One of the highlights was revisiting Performance’s famous ‘Memo from Turner’ sequence: Jagger sings, Ry Cooder is on slide-guitar, and Roeg and co-director Donald Cammell concoct a glorious headtrip of a pop video within a movie. But my favourite musical moment of the films – perhaps my favourite moment of the films outright – was the opening sequence of the twisted love-story Bad Timing. In it, Art Garfunkel and Theresa Russell – and the camera – gaze at the works of Gustav Klimt in a Vienna gallery. Tom Waits’ unbelievably beautiful ‘Invitation to the Blues’ plays over the top. It’s a stunning, luscious opening, which sets the mood for the film perfectly.

Truth is, I’m a sucker for all things Tom. Seeing him in concert on two consecutive nights in Paris remains the best 28 hours of my life. Listening to Tom Waits for the first time made me realise I should bury my Lightning Seeds, Cast and Kula Shaker CDs in the darkest parts of the garden. Since those days, my musical interests have swayed this way and that, but some have never fallen from favour: Slint, Shellac and Nick Cave, to name a few. But, old Tom has always stood tallest. It’s a moment of joy whenever he crops up unexpectedly. So seeing him matched with Klimt and a sexually-deviant Art Garfunkel in perhaps my favourite film of one of my favourite directors – what else could one ask for?

Elin Williams

Huw Chiz

I like to think of myself as a sort of musical chameleon. That’s quite a brave statement to make for a twenty-something year old, as older people tend to sniff at that, but I am quietly confident that I can out-Smiths you, and can also cover the top ten singles chart every week. I’m the one friends look to with hope in their eyes when the music category is announced in a pub quiz. I think it’s because I listen to things pre-1990. Everybody seems to claim that their musical tastes are ‘eclectic’, but I’ll just say that you are not truly eclectic until you start hiding your iPod playlist from people at the gym. I often wonder what would happen if my earphones fell out and everybody knew I was listening to ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Kate Bush as my ‘pump it up’ motivation.

One thing that has always been a musical constant in my life is Welsh choral singing. Going to a Welsh school where singing is an inherent part of the culture, it has always felt quite natural and normal to me. Recently, my friends and I started a Youth choir so we can compete in the Eisteddfod and the like. Some of the songs I’ve learnt in the recent months are truly magnificent and sound absolutely beautiful when sung with four-part harmony. We’ve recently started singing a song which is familiar to many choirs, a song called ‘Y Cwm’ written by the mighty Huw Chiswell. The tune is a reminiscence of the old days prompted by the meeting of two friends. The lyrics begin ‘Wel, siwd mae’r hen ffrind’ and go on to explain how they haven’t seen each other since one left the valley that was simply ‘too small’ for him. They talk of the days that they would walk to the mines with their fathers, thinking they were big men. The song sees a decent into the sad reality of the pits being closed down and thus an end of an era, and an end to their childhood. Significantly, this song is one which simply demands dialectical ‘polishing’ from choirs. It’s imperative to sing with a relaxed valleys accent. I don’t know why, but it’s certainly a change from having to round off your vowels and enunciate until your cheeks hurt. It’s a real, solid, poignant valleys classic. The tune is one that simply has to be heard, so I urge you to go and have a listen if you haven’t already done so.

John Lavin

‘Stay Together’ by Suede

To begin with let’s be clear. I’m not talking about the radio edit of ‘Stay Together’ that appears on so many compilations and which has tended to cause people to think of the full 8:28 mins version as a superfluous extravagance. Listened to in this edited form ‘Stay Together’ can seem to be little more than a superior version of their poppy previous single ‘So Young.’ No, I am talking about the full, eight-and-a-half-minute hymn to Bernard Butler’s father. The version that starts with ballet-like guitars so fluent and sad and standing-on-a-street-corner cool they give you an adrenalin rush and break your heart all at the same time. The version that moves from ‘Space Oddity’-stratospheres to stormy, Passion of New Eve-esque inner city maelstroms in the blink of an eye. All before taking you back to that tear-stained ballet that somehow conjures Eric Clapton’s contribution to George Harrison’s ‘I’d Have You Anytime’ and makes it sound A. far more beautiful than it already is and B. sleazy and glam into the bargain.

It is within this mixture of the iridescent with the gutter, of course, that the genius of Butler-era Suede lies. The guitarist famously decried the fact that for ‘Stay Together’ b-side ‘The Living Dead’ he had “written this really beautiful piece of music and it’s a squalid song about junkies.” It is this contrast, of course, which makes the song so special. (It is worth noting that his musical hero Johnny Marr similarly bemoaned Morrissey setting the frivolous lyrics of ‘Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others’ to one of his most ‘beautiful piece[s] of music.’) For Butler’s grief stricken ‘Stay Together’, meanwhile, Anderson decided to channel a stream of consciousness lyric about suicide, heroin and a volatile girlfriend he was dating at that time, (the real reason he dislikes the song according to his former publicist Phil Savage), while also using the most clichéd phrases – ‘Nuclear Skies’, dancing ‘in the poisoned rain’ etc. – he could possibly think of.

The deliberately throwaway quality of most of the lyrics might very well be spiteful but they might also be a ploy to create a stuttering juxtaposition with Butler’s more grandiose leanings. The truth is probably somewhere in between. Either way it works. Serving to create a unique pop universe that neither Anderson or Butler have ever quite managed to achieve on their own. Like Lennon and McCartney, or Morrissey and Marr, they are ideal counterpoints to and editors of each other’s material.

The song reaches it’s denouement with a suddenly heartfelt Anderson pleading with someone (perhaps the encroaching Britpop hoards?) not to ‘take me back to the past again’ and to ‘take me somewhere else’. Cue Butler unleashing his radiant ‘I’d Have You Anytime’-isms. Huge, bellowing, antithesis-of-Britpop-trumpets follow, (although they are played by soon-to-be Britpop-go-to-men The Kick Horns), and then after a few desolate bars on the piano, there is a long echoing drone that sounds a bit like a departing tube.

Butler later said that “Whatever I did on ‘Stay Together’ was the A to Z of the emotions I was experiencing [after his father’s death] … defiance, loss, a final sigh.” Listening to its Evening Session premiere one January school night in 1994 – on headphones, as ever, on the family hi-fi while my parents watched TV – I felt, and probably still do, that I had never been more moved or heightened by a piece of music than I had been by ‘Stay Together.’

Nigel Jarrett

‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ by Charles Mingus

Serendipity is what makes music such an ever-expanding source of joy. Without constant discoveries – and re-discoveries – one abides by the safety of what one knows, and that’s the reason why concert promoters dither in programming anything they believe might not go down well with an audience in the mass. More seriously it has slowed the acceptance of so-called contemporary music, often so far removed from the average listener’s armchair zone that its position can appear embattled. But if you don’t listen to it you can never have an opinion about it. More often these days and as I get older I’m listening almost exclusively to music written by living composers. And it’s not just today’s music that many listeners shun: the unfamiliar – a Donizetti opera that isn’t Don Pasquale or Lucia di Lammermoor or L’Elisir d’amore, for instance – is not considered a productive investment.

The joy of re-discovery lies partly in the realisation that you were right in your estimate of a piece of music and partly in the undeniable feeling that it means more to you now than when you first heard it. When I first heard ‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ by the Charlie Mingus band in 1959 – the album on which it appeared was the seminal Mingus Ah Hum – Lester Young was my favourite tenor-sax player. The Mingus tune is an elegy for ‘Pres’, as Young was called (he always wore the eponymous titfer), but its most magical quality is that it’s a jazz elegy, a kind of very slow foxtrot – strictly, it’s in duple time – that would still work however much the musicians applied an over-arching accelerando. (In that, it would be a reminder of early jazz and the New Orleans tradition of marching bands which accompanied the dead to the grave in mournfully slow tempi and returned to the wake with riotous abandon. Perhaps they still do).

There are other features, related to the instability of both the composer and his subject (the reason why the tune starts and ends as an elegy) and Mingus’s habit of conceiving his tunes in workshops and composing on the hoof, confirming that music always benefits from as much relevant extra-musical data as the listener can discover. If you didn’t know about the compositional provenance of ‘Goodbye Pork Pie Hat’ it’s extemporised feel would still be undeniable.

Jazz is currently enjoying a boom time with the re-issue of old albums – ‘old’ meaning anything around before a recording became unavailable. For this listener, old means new and, in the case of that Mingus tune, freshly-minted.

James Vilares

‘For the Shores of Your Far-Off Native Land’ by Alexander Porfir’yevich Borodin

Hiraeth is a fascinating concept, one which only really makes sense for the expatriate (I wonder if Dylan is feeling it yet?). I’ve written about it’s Galician equivalent, morriña, before when reviewing the book launch for Craig Patterson’s fantastic translation of Eduardo Blanco Amor’s On a Bender here. There’s something about facing the Atlantic, something about the sea itself that creates a sense of malady of the soul. It’s a difficult concept for the English-only speaker to grasp, but I have the answer for you.

Lock the doors. Take the phone off the hook; put the mobile on silent. Close your eyes and lie back on the sofa. Cross your arms and place them on your chest, as though floating on a medieval funeral barge. Put ‘For the Shores of Your Far-Off Native Land’ on your CD player. And then press play.

What you’ll hear is not for the optimist. Borodin’s mournful dirge for voice and piano is a deep experience, a journey into distant realms of woe, and I use the word not in the melodramatic sense, but in its true, despairing fullness. There’s a sense of detachment from home, a sense of helplessness, watching from afar the sufferings of your people. You can well imagine Solzhenitsyn’s Shukhov singing this as he lays line upon line of block on mortar in the Gulag, looking over the wall across the tundra towards a home which he has no hope of returning to.

It’s also the song of two lovers, hinting in classical the deep connection with home that Jack Peñate was getting at in ‘Torn on the Platform’ (BTW, this one’s for the jolly among you). But unlike Peñate’s syncopated ska beat, ‘For the Shores…’ is anything but bouncy; it builds its power gradually, slowly climbing, circling towards an energetic, almost painful climax. And the quietness of the aftermath belies the sadness of a hopeless future which is all that can be expected.

But I find it’s despair somehow cathartic, bestowing on me, at least, a certain positivity arising from its still-glowing ashes. So if you’re an expat and missing home, or perhaps even feeling disenfranchised at the state of things, get a decent dose of depressive dirge with Borodin, and then join me as I look on the brightside.

Cath Barton

4’33” by John Cage

John Cage’s 4’ 33” is a piece more talked about – and often misunderstood – than performed. Some years ago the toy piano virtuoso Margaret Leng Tan included it in a concert she gave at St George’s in Bristol which I attended. On 28th September The Bartons (of whom I am half) made it the centre of a set at the BOSCH Harvest Festival at the Barnabas Art House in Newport. Serendipitously one of the other performers that night told me she had collaborated with Margaret Leng Tan on that occasion in St George’s – a Cageian co-incidence which I’m sure the man himself would have liked.

While it would normally be hubris to ‘review’ one’s own performance, I think it is a different matter with 4’ 33”, where the performer(s) – in this case singer and keyboard player – are instructed by the composer to make no intentional sound for four minutes, thirty three seconds. So it is the audience who perform, their sounds we hear. In this case there were little fragments of conversation, a bit of giggling, a bit of sshing as people walked through the room. Most of all, a space opened up for people to stop, to think, or just to be. No-one heckled – although that would have been okay! – and no-one left. Afterwards we had some of the most engaged conversation about contemporary music which we ever had after a performance.

4’ 33” will be different every time it is performed, as was John Cage’s intention. And of course it doesn’t have to be done in a concert hall. Try doing it walking down the street, for a length of time of your choice. Close your mouth, open your ears and listen, really listen, to the music of the world around you. I think you’ll be surprised.

Jamie Woods

Rewind the Film by Manic Street Preachers

Nicky Wire had previously declared their 2010 LP Postcards from a Young Man to be ‘one last shot at mass communication’, but Rewind the Film, the eleventh album from the Manic Street Preachers, is their most honest and accessible work since their 1990’s heyday. Unlike its predecessor there’s no electric guitar, no classic rock posturing. Acoustic guitars and soft synths dominate this soundscape.

‘I don’t want my children to grow up like me’

‘This Sullen Welsh Heart’, the album opener, sits somewhere between the Larkin poems ‘This be the Verse’ and ‘Annus Mirabilis’. It’s a lamentation on succumbing to cynicism, to anger, to self-loathing. ‘The hating half of me has won the battle easily’ is the key to this song, and to the album – we can’t let that happen to us or to our children. Then, like a rallying cry, the brass-laden ‘Show Me The Wonder’ kicks in, an uplifting glorious celebration of the world, the perfect antidote to ‘This Sullen Welsh Heart’s despair. ‘Show me the wonder’ it exclaims. ‘I have seen miracles move in reverse’.

Rewind the Film sees the ghostly reverberating vocals of Richard Hawley desperate to ‘see it all again’, and the beautifully elegaic ‘I’d love to see my joy, my friends’. It plays on Hubert Selby Jr’s idea that before he died, he’d regret his entire life, and he’d want to live it over again, which was quoted on the Manic’s own The Holy Bible. It’s also similar in theme to other moments of their now extensive back catalogue – ‘La Tristesse Durera’, ‘Die in the Summertime’, and the heart-wrenching ‘William’s Last Words’.

It’s hard to listen to this record without seeing these reflections of the Manics’ past selves – whether it’s the glimpses of the Motorcycle Emptiness video that come to mind listening to ‘(I Miss The) Tokyo Skyline’, or the genius of Richey James in the melancholy prayer ‘As Holy as the Soil’ ‘please come home, it’s been so long’.

‘How I hate middle age, In between acceptance and rage, Democracy has made a fool out of me’

These lines from ‘Builder of Routines’ make it clear where the band are, politically and personally. In ’30 Years War’ they’re not suggesting attacking the ‘Old Etonian scum’, but instead asking ‘What is to be done?’ This is a band that now know they can’t beat this system, but they can put it under the spotlight. This is the Manics at their barest, rawest, truthful best, musically subtle, lyrically rich.

Jonathan Taylor

Johann Sebastian Bach, Fantasia and Fugue in C Minor, orch. Edward Elgar, BWV 537 / op.86

I love both Bach’s and Elgar’s music, but I’d never encountered the latter’s orchestral transcription of the former’s organ work, the Fantasia and Fugue in C Minor of c.1723, until one drear morning a few weeks ago, driving in the early-Autumnal rain towards work, it suddenly burst from Radio 3, filling the inside of the car. All sealed up with this remarkable music, isolated from the rain and greyness and queues outside, I felt it was driving, not me: and I recalled that apocryphal statistic that more car accidents are caused by Wagner’s music than any others. If not actually Wagner, Elgar’s transcription of Bach is definitely Wagnerian in its orchestral grandeur, its crazy Romantic hyperbole, its Stokowskian Technicolor; as he himself rather hubristically put it, he ‘wanted to show how gorgeous and great and brilliant [Bach] … would have made himself sound if he had our means.’

As well as Wagnerian and Stokowskian, the piece is also positively Elgarian: as one listener put it, this is more Elgar than Bach, a kind of lost, contrapuntal Pomp and Circumstance March – the final bars of the Fugue particularly come across as march-like in Elgar’s transcription. The listener who said this said it disparagingly: he preferred Bach-as-it-is, and felt that, by Elgarising the Fantasia and Fugue, Elgar had ruined it. I think this misses the point of transcription: at its most radical, transcription is the creation of an entirely new piece, using pre-existing materials. No doubt there’s a whole spectrum of modes of transcription, as there is with poetic translation, but at one end of the spectrum is the reshaping of old materials into something entirely new. That is what Elgar does here: he takes Bach’s organ work and turns it into something only he could have written, and which belongs firmly to his – not Bach’s – age. Maybe transcription, in this way, exposes something about the creative process in general: it is always a borrowing, always a form of transcription of pre-existing materials, a making new of the old – all of which has implications, of course, for our casual assumptions about authenticity and intellectual property. ‘All property is theft,’ as Proudhon famously remarked.

The question of property is pressingly political in the case of Elgar’s transcription, given the date of composition and first performance (1921-2). In the wake of the First World War, it was a political act for the most famous British composer of the day to orchestrate a monument of German culture; and this was explicitly so, because the piece was first envisaged as an act of mutual reparation between Germany and Britain. Originally, the plan was for Richard Strauss to orchestra the Fantasia, Elgar the Fugue, as an expression of a new bilateral understanding. Characteristically, though, Strauss did not hold up his side of the bargain, so Elgar ended up orchestrating both sections of Bach’s piece.

He did so in lieu of other inspiration. In the wake of the devastation of the First World War, and his own personal tragedy – the death of his wife in 1920 – his inspiration dried up, his breed of Romanticism came to seem old-fashioned, and, like so many composers of his generation, he stopped composing much. ‘I can’t be original and so I depend on people like John Sebastian for a source of inspiration,’ he said. But in a sense he was wrong, or at least being overly simplistic: the transcription is original and unoriginal at the same time. Its means and sound-world are definitely Elgarian, even if its materials are taken from Bach; and, as many others have said, perhaps, in a distilled form, all artistic creation consists of this kind of process: that is, the appropriation of old materials and their transcription into new forms.

Carl Griffin

The Last Member of the Levellers

The Levellers shaped my identity in my teens. Firstly, I hold the lyrics responsible for turning me vegetarian, as well as turning me outraged at every scrap of injustice I encountered, until my waist-reaching hair was cut, taking my humanity with it. Although that influence did not continue into my twenties. Secondly, it was my way into the folk, country and blues music I still love today. I have always thought of the Levellers as the greatest folk band in my lifetime. The band themselves might shy away from the ‘folk’ label, but that’s exactly what the majority of their songs are. Rocking folk, but still folk.

The Levellers have never ‘sold out’, despite what some former fans might say. They still hold the beliefs they held when they released their very first album, A Weapon called the Word. I myself have ‘sold out’ since then several times, but I still love these songs, especially up until, and including, Mouth to Mouth. Mouth to Mouth was perhaps the Levellers’ biggest success in commercial terms, although, unlike their album Zeitgeist, it did not reach the top of the album charts. The song ‘Beautiful Day’ seemed to be on every advert or TV clip set on a beach for years. In Swansea you can hear it at the Liberty Stadium every match day.

In my very early teens, I bought my first Levellers single, on a whim, having never heard their music before. It was a cheap single and I bought it for the sake of it really. While my friends and I waited at the bus-stop ready to go home, two big, bad bullies tried to pump some money out of us. Seeing my tape, one of them tried to take it from me. At that point I hadn’t discovered the greatness of the Levellers. I often wonder what might have been had I given up the cassette. If the music we listen to shapes who we become, might I have become someone else, especially if I had settled on a band from a different genre as my ‘favourite band’? Saying that, I have also loved Bob Dylan and Tom Paxton since my early teens, so I’m sure I would have turned out fine anyway, morally speaking.

That cassette was one of the singles from the Mouth to Mouth album. Possibly because it was the first Levellers album I got into, Mouth to Mouth is by far my favourite Levellers album. ‘Dog Train’ and ‘Celebrate’ leave me with the sense of magic every time I hear them. Those songs aside, though, I love to go back to the first Levellers album, A Weapon called the Word, most of all, where the fiddle was at its best and a harmonica chipped in to make one of the best, and most original, still, folk albums I have ever heard.

Jemma Beggs

My Musical Confession

Recently, I found myself humming a tune I just could not seem to get out of my head. Eventually driven almost to distraction I had to ask. ‘What is that!?’ To my horror and shame the response came back ‘Oh, it’s off that advert’. Now let’s get one thing clear – I loathe and detest adverts. I am someone who mutes, fast forwards, changes channels, anything to avoid the dreaded ad breaks. Obviously I had not been vigilant enough however, as there I was merrily humming along to this seemingly innocent song whilst blissfully unaware it had snuck its way in from the great brainwashing abomination that is advertisements.

But I suppose that is exactly why ads use music, because there is something so immensely alluring about it. I find it truly amazing that almost everybody has this immense capacity to remember lyrics – a seemingly unlimited collection of lyrics. You can hear a song you once loved a year, two years, even 10 years later and sing every single word without pausing to think. And music is so addictive; when I hear a song I love I know I’ll be listening to it every day for the next month at least, and most likely on repeat. (I remember one particular car journey when I was around 10 years old where I listened to ‘Stacey’s Mom’ by Fountains of Wayne exactly 13 times in a row. Not my finest hour I admit but a fine example nonetheless!) What other art form would evoke such a response? People don’t watch the same fantastic film or read the same brilliant book day after day. So what is it that makes music so magnetising?

For me it is music’s fascinating ability to incite incredibly strong emotions and memories. There are songs that make me cry, that make me smile and even some that fill me with rage. I love how one song can create such an amazingly vivid memory, so that in future whenever and wherever I hear it, it transports me completely to that moment in my life; that summer, that party, that relationship, that break up. Of course not all songs have positive connotations. There are some I can’t listen to at all, whether it be because they conjure memories too painful or because they are just downright annoying but on the whole music makes me glad to be… well just to be.

(And if you must know it was ‘She Like The Mango’ from the Rubicon adverts). Oh the shame…

Jon Gower

Sibelius Symphony No. 5

There are those favourite moments – the thrash of guitar chords as the Manic Street Preachers’ ‘Motorcycle Emptiness’ revs up, the mariachi crystal meth manufacture sequences in Breaking Bad, or Aretha Franklin saying her little prayer and then there are those moments of complete and utter transcendence. It happens when the great, late Sufi singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan sends his voice aloft to search for God on devotional Qawwali (and crossover) albums such as Mustt, Mustt, as his fellow musicians build a temple of music all around him.

But for me, above all others it’s there in Sibelius’ 5th symphony and in particular, in one passage which literally takes my breath away. It comes some twenty minutes in, but anticipated right from the outset. I can hardly breathe when I hear it, so beautiful is it, like tuning in to the very music of the spheres. The French horns blast out a fanfare as if announcing the arrival of God, or something equally momentous, meanwhile the strings provide a dancing undertow. If Walter Pater was right when the suggested that all art aspires to the condition of music, then, for me, this is the benchmark of all other art, the perfect conjunction of noise and meaning and emotion. It conjures up huge, complicated, Cinemascope mental landscapes and reminds one that finding and then developing a grand musical theme (in this symphony there are two in play) can create the most sublime art from the very simplest things, from notes on a page. From vibrations in the air.

Sibelius’s 5th is a deeply generous piece of music I return to pretty much monthly, just as I re-read Elizabeth Bishop’s poem called ‘Poem’, which I’ve been reading for about fifteen years. Doing so reaps ample rewards which seem to multiply and deepen with each revisit, as the works seem to change, or maybe it’s just me.

Steph Power

Yamaha YZF-R6

You might take the following as evidence of a Guest Editor having gone slightly off her rocker – and you might be right to wonder. But, as I sat down to consider which one alone to share of the many, many extraordinary musical moments I have experienced – both positive and negative – as composer, performer, teacher and listener, I found myself coming back time and again to one thing amongst the harmonies and rhythms; the Berg and Lachenmann; the Andriessen, Archie Shepp and Patti Smith: and that is, motorcycles. Well, not all motorcycles and certainly not just any but, specifically, the howl of a 600cc racing in-line four cylinder at full chat. More specifically, the howl of said beast from on board, whilst tearing down a 140mph straight on a race circuit in pursuit of another motorcycle.

You might take the following as evidence of a Guest Editor having gone slightly off her rocker – and you might be right to wonder. But, as I sat down to consider which one alone to share of the many, many extraordinary musical moments I have experienced – both positive and negative – as composer, performer, teacher and listener, I found myself coming back time and again to one thing amongst the harmonies and rhythms; the Berg and Lachenmann; the Andriessen, Archie Shepp and Patti Smith: and that is, motorcycles. Well, not all motorcycles and certainly not just any but, specifically, the howl of a 600cc racing in-line four cylinder at full chat. More specifically, the howl of said beast from on board, whilst tearing down a 140mph straight on a race circuit in pursuit of another motorcycle.

The sound that assails the ears above the wind-roar is like nothing I have experienced anywhere else. It is a roaring shriek of exhilaration that courses through the body from head to toe, hand to heart – and it is music. Or a form of it. It is music that sings of freedom and risk, of joy and the oneness of woman and machine; Fluxus Music in a sense that John Cage would surely have recognised, but on which your life literally depends as you merge with the engine’s rise and fall. A change of pitch means time to shift gear, a blip of the throttle – when to accelerate or back off NOW before that fast-approaching corner.

And as you reel in that other bike, the most incredible aural phenomenon occurs. For the closer you get, the more the sounds of the two bikes weave together; at first like a kind of echo as you hear the first bike speed up and slow down a fraction before you do, following behind. But, as you draw alongside to overtake, there is a moment which seems to last forever, where the two engine notes waver in and out of phase; in unison, out of unison; microtonally together and apart, creating an aural and physical sensation like being split apart into atoms and reassembled – or, at least, how I’d imagine that to be. It is magnificent and it shakes you to the core.

My biking days are over now, but I was reminded of the musical and emotional power of that experience from an unlikely, introspective source last week, in a striking performance of Berios’ Sequenza V for trombone at Arcomis. I wondered what it would feel like to play rather than merely listen to such reverberating multiphonics, microtones and subtle changes of timbre – the solo, physical joy of being inside them, as the trombonist was, singing into his instrument. And I remembered the badge on my Yamaha of three tuning forks overlaid.

Gary Raymond

‘I Follow You’ by Melody’s Echo Chamber

I was late coming to Melody’s Echo Chamber, the musical project of French songwriter Melody Prochet and Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker. The eponymous debut album was release late in 2012, but it wasn’t until early 2013 when I first came across the opening track, ‘I Follow You’. I was still a little shell-shocked at the magisterial beauty of Bowie’s ‘Where Are We Now?’ at the time, I suppose, and maybe I needed something a little more dreamlike, wispy, and romantic. But ‘I Follow You’ has stuck with me, as has the Bowie single, and for largely the same reason, if very differently expressed: nostalgia really gets under the skin. Well, anyway, ‘I Follow You’ is my song of the year.

But just to be complicated, I’m not choosing my song of the year as my musical highlight: I’m choosing just the first ten seconds – the guitar riff, swinging piquantly in the air on its own, right up until the moment when the drums clip in and take the song off to its fresh/familiar homage/nod to the past/future of classy pop.

There is something sweepingly cinematic about that opening riff. I see Alain Delon walking down the street with Brigitte Bardot, the pastel-coloured svelteness of Plein Soleil for him, and almost certainly matched with Bardot’s finest moments from Godard’s Le Mepris. But more than that, the riff is not just evocative of an era of chanteuse cool. It is what Johnny Marr would have sounded like had he written for Motown. Only it isn’t Motown, is it? It’s Stax, Motown’s grungy cousin. But at the same time you can’t get away from the soft centre and lilt to it. It’s ‘What Difference Does It Make?’ produced by Serge Gainsbourg for a Françoise Hardy early ‘70s Warner Bros record. Indeed you can hear everything in that riff – Velvet Underground in its dour jaunt, Can in its cascade, The Smiths, Josef K, The Shangri Las, and perhaps even more delightfully, the lazy, sexy shoulder swaying of St Etienne and nineties girl Indie pop.

It is a brash electronic record, one that distorts the EQ by the time of the languidly beautiful chorus, but the riff has the plectrum tactility of an acoustic track. It is joyous in its Gallic subversion of the minor chord, triumphant in the journey to the ends of its awkward rhythmic swagger. A riff so enthusing, so filled with the stuff of great soul and great vintage Euro pop, that it is nothing less than a minor miracle that the song it sprouts lives up to it. Prouchet is every bit the touch of class, and the band are always in that tantalising space between trailing off into disinterest and ramping it up into a full blown Northern Soul stomper. And on top of that the album that it opens is bloody good, too.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis