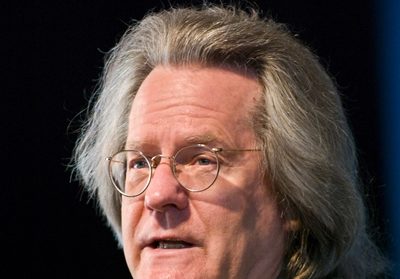

Richard Holloway, the former Bishop of Edinburgh, examines how anyone can claim a complete understanding of the mystery of existence in his chat with AC Grayling.

Richard Holloway, ‘boy of the hunger classes’, fell in love with the ‘incense, light and magic’ of the Church as a fourteen-

It is a poetic description and Holloway’s love of the written word – Philip Larkin, Matthew Arnold – runs through much of the convivial debate he has with his friend, the old Socratic sceptic AC Grayling. But above and beyond the talk of ‘wistfulness’, the claims that ‘walking is the new churchgoing’ and that ‘the religious hijack [humanity’s] lust for the transcendent’ and that ‘all [evangelicals] do is talk at each other and play guitars’, the crux of the debate fixes on the figure of Jesus, who remains – despite all of Holloway’s new-

Describing himself, intriguingly, as ‘a Christian agnostic’, Holloway’s ‘walking away’ from the Church and ‘taking to the hills’ was largely the result of his employers being ‘stuck with social and cultural attitudes from the early Bronze Age.’ He likes Anglicanism as a branch of Christianity because, like human beings, he feels it is ‘muddled’. What he can’t stand is the way the Church has torn itself apart over an unhealthy interest in other people’s sex lives. Holloway describes the 1998 Lambeth conference – ‘700 men in pink frocks’ – as ‘the ugliest thing I’ve ever been at… one bishop said it was like a Nuremberg rally; something kind of died in me.’ This was the debate over homosexuality, where numerous African bishops took to the floor to denounce softening Western attitudes.

In its wake, Holloway ceased to follow the teachings of the Church; instead, he followed Jesus. According to Holloway, the core Christian teaching is that ‘nothing should get in the way of human compassion, especially not religion.’ He quotes a couple of the best-

His interlocutor can’t help wading into the debate at this point. For AC Grayling, the empiricist, Holloway, with his continued belief in original sin, is a pessimist. Holloway prefers to think of himself as a realist: ‘We are capable of great cruelty’. Grayling cites Stephen Pinker’s recent book The Better Angels of Our Nature, which traced the decline in humanity’s capacity for cruelty. Between them, the two men on stage have pushed the audience into a place where – whatever our personal views or beliefs – we realise that much of the rest of the argument hinges ultimately on our view of human nature.

‘I love you Anthony, but don’t push me into a corner,’ says Holloway at one point. These are two men who love debate, but while AC Grayling is on a rational quest for certainty, Holloway – the ’Christian agnostic’ – positively celebrates ‘the beauty of uncertainty’. ‘Don’t accuse me of turning doubt into a metaphysical absolute,’ he says, meeting the philosopher in his own language, ‘I’m talking about it as an existential experience.’ And the question-

But amid all this uncertainty, what is an absolute for Holloway is that ‘ultimately God has to carry the can for [the ills of the world] because everything comes from that Big Bang moment.’ Derrida reminds us, ‘if there is such a thing as forgiveness, it has to be of the unforgivable’; Holloway’s own addendum to this: ‘the only alternative to absolute forgiveness is absolute punishment’.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis