The British Council Lecture

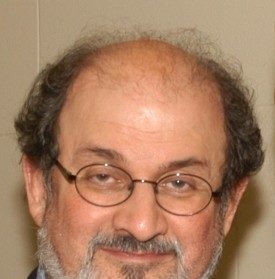

The appearance of Salman Rushdie at a literary festival is never merely an exercise in promoting his latest book. Last time Rushdie was at Hay was his first public appearance since the Ayatollah Khomeini issued the notorious fatwa. Last time he was scheduled to appear – at Jaipur in India – the novelist had to pull out because of death threats.

This time, mercifully, there is little ado. Rushdie appears, talks about his life in books with Peter Florence, is handed a white rose in the traditional Hay gesture, and disappears back into the green room. The audience trudge out into the pouring rain, throw a few coins into the collection buckets for humanitarian relief in Sri Lanka and head to the mud of the car park.

Nothing to report? Well, not quite. It’s just that on the face of it, this is a Hay event like any other. Rushdie talks about how Midnight’s Children was born out of a joke of his father’s: ‘Salman was born, and eight weeks later the British left’ and makes a few jokes of his own. ‘I have trouble with great writers who don’t have a sense of humour,’ he says, naming Alexander Solzhenitsyn. To be fair, as Peter Florence points out in response, ‘there wasn’t much to be funny about [in the gulag].’

‘But repression, sometimes, breeds humour,’ Rushdie maintains. He should know, I suppose; it must be difficult maintaining one’s sense of laughter under threat of death. And this is the thing about this year’s British Council lecture. There is no need for anything overtly political to be said. This is simply a writer talking openly about his craft and his influences, in a free country.

Rushdie talks about the Indian roots of the 1001 Nights, his brief period of overlap with E.M. Forster at Cambridge – ‘it was trying to write unlike Forster that I found out how to write’ – and the ‘Bollywood idea’ of the baby-swap that informs the forthcoming film version of Midnight’s Children. So dramatically satisfying did Rushdie find the moment of realisation necessary in the cinematic medium, he thinks he would have included it in the book if he’d thought of it at the time.

He also talks about form: the way that in contrast with the ‘big baggy monster’ of his ‘Booker of Bookers’ about India, his ‘Pakistan novel’ Shame, is tightly formulated and in its protégé-becomes-executioner storyline is Shakespearean in its resonances. However, for Rushdie, Pakistan is ‘a tragedy performed by clowns’.

When the conversation does inevitably touch on The Satanic Verses, the novel that inflamed so many Muslim sensibilities, Rushdie is keen to talk about the themes of the book itself rather than the political storm that surrounded its publication. At its heart, it is a book about migration; as he had ‘done’ novels about India and Pakistan respectively, now he turned his attention to partition and the Great Migration.

‘The age in which we live is the age of migration. There are more people living in countries in which they were not born than ever before, than in all of human history put together. Any big city is hybridised, diverse. The end of the monoculture is the biggest thing in our generation.’ As a first-generation migrant himself, Rushdie believes that migrants lose all four of the elements that give an individual rootedness: place, people, language and cultural assumptions. The dilemma of the migrant is what you absorb from your new world and the traditions you choose to keep from the old. His reaction to migration was to ‘question belief systems’. He adds, with mischievous understatement: ‘that’s what some people didn’t like’.

Then the conversation takes its inevitable turn. ‘Freedom is the ability to have the argument. The first thing un-free societies do is stop the argument.’ And for Rushdie, the ‘novel is a crucible of debate’ and the English language its gold standard currency. ‘You can do anything with gold; it’s incredibly malleable.’ By way of demonstration, he mixes up the syntax of his sentences. The syntax of his sentences he mixes up. Of his sentences he mixes up the syntax. Like that. The funniest thing about this short exchange is Peter Florence’s refusal to play along, letting this most linguistically gifted of novelists babble his way into nonsense.

When Rushdie does manage to break out of his loop, he proves his point by references to Joyce and Proust, and the way Hamlet is tragic, comic, historical and romantic all at once; Joyce particularly is a touchstone for today’s conversation, his being a writer in English who ‘created an English that didn’t belong to the English’. And this, ultimately, will be Rushdie’s epithet too. Much more than a writer who has more than once been threatened with death for the words he has chosen, the recognition of Rushdie’s work has been for the way it has gone far beyond any ‘post-colonial’ tag that might once have been applied to it, to speak for the age it inhabits.

As questions come in from the audience in Hay, but also via the Florence iPad from Kerala and Mexico, we are reminded of the global thirst for literature in English. As Rushdie jokes: ‘I wasn’t writing for mullahs. I didn’t think they were my target audience.’

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis