Hope: A Tragedy by Shalom Auslander is in fact a mercilessly tight black comedy. One you feel you’ve been sewn into and can’t unzip. It could as easily have been called Fear: A Comedy; that’s what the book is, after all – an hilarious meditation on fear – but that would be to undermine the greater implications of the tragic nature of hope. And that’s precisely what Auslander’s requesting us to consider, from beginning to end. Relentlessly. It’s a neat, intelligent and skilful novel full of philosophical cant a la de Botton. An unremitting mood of claustrophobia – attics; the pervasive smell of excrement – stands as a metaphor for the pace, pressures and alienation of twenty-first century living.

The plot: young family moves to suburban small town to escape the dangers and complexities of contemporary urban America. Counter-

There’s a resonance with the canons of Woody Allen and Philip Roth, so if you don’t like neurotic, intellectual, Jewish, New York, liberal, introspective angst, don’t read this book. If, on the other hand, you can’t get enough of it, you won’t be able to put it down.

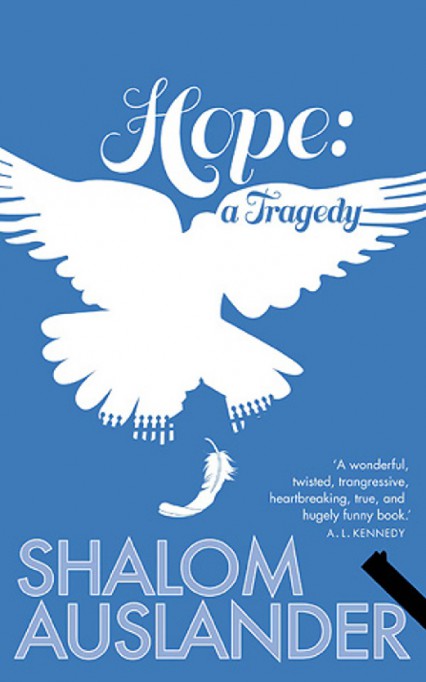

by Shalom Auslander

292 pages, Picador. £16.99

At points I’m reminded of Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. Like Franzen’s Walter Berglund, Hope’s anti-

The sun was in the sky like a something. The breeze blew like a whatever.

There’s a part in the book that reminds me of The Bell Jar’s Esther Greenwood. When Plath’s heroine descends into madness, her relationship with the written word fragments and the novel she is attempting to write becomes gobbledegook. Similarly, Kugel’s relationship with his sales spiel fractures into nonsense the more he loses sight of any meaning or connectivity with the world. There are more parallels than you’d think between The Bell Jar and Hope: A Tragedy. Both are darkly comic investigations into cultural alienation. And sticking with Plath for a moment, this relatively minor point leads to a more obvious parallel: her controversial holocaust references in the poem ‘Daddy’, provoking outraged criticism. How anyone could solipsistically assume the voice of a holocaust survivor without having experienced it gave her critics plenty to lambast. Her Jewishness was seen as immaterial in the conceit.

I told my neighbours I was reading a black comedy by an American Jewish writer in which the protagonist discovers Anne Frank hiding in his loft, and the light-

What’s more important here is his examination of suffering and the relative experience of pain. Auslander does something really triumphant by setting his banal salesman hero against a backdrop of acquisitive memory and circumspect associations with one of the vilest atrocities of recent times. As a society we’re obsessed with reading novels about hardship and suffering: we devour books set in the second world war, in Afghanistan, and other war zones. We’re vampirically drawn to tales of past woes and remote agonies, preferring to ignore the alienation and anxiety of living in the prosperous West, perpetuating a myth of success. There is little room for failure, even less for any compassionate examination thereof. Reading about war and tragedy makes us feel worthy. Thinking about our own friends’ and families’ fears and failings makes us cringe.

Throughout the book, Shalom Auslander in fact approaches the holocaust with sensitivity: the section in which he remembers a childhood ‘trip’ to a little-

It seems to me that Hope: A Tragedy is really a book about compassion, or its deficit in our culture. This seemingly tongue-

The most telling character in the book for me is Vince, the hardware shop owner. Whilst Kugel grapples with a catalogue of moral and familial dilemmas and obligations, Vince speaks for a humourless and shut-

By the end of Hope, entirely absorbed and over-