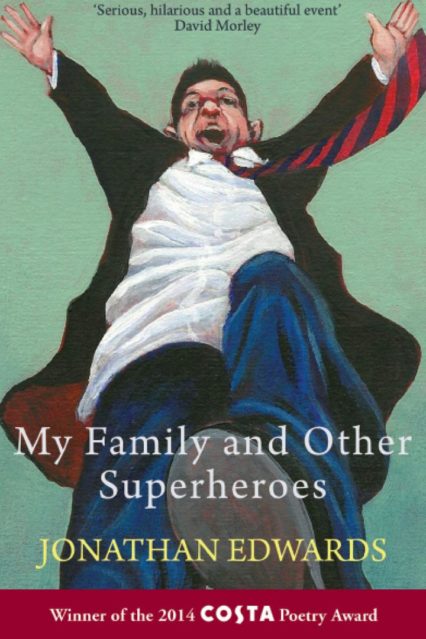

In the latest of our series, Costa-winning poet Jonathan Edwards unravels the writing process of his debut collection.

I wrote My Family and Other Superheroes using a pen and some paper. This may seem like a facetious way to begin an article entitled ‘How I Wrote,’ and that’s mainly because it’s a facetious way to begin an article with that title, but I also start with that sentence because it’s true, and strikes me as important. When I was about fifteen, I wanted to be Quentin Tarantino, and in the one interview I saw him give about his writing process, he talked of the quasi-religious importance of going to the stationery shop for pens and paper, and telling himself that these were the pens and paper with which he would write Reservoir Dogs.

For me, the pens in question are BiC 4-way multicoloured pens. I’ve arrived at them through many experiments, from 10-way Darth Vader-head pens (lovely, but cumbersome) to my father’s elaborate and super-expensive prize fountain pen (lovely but, I found to my horror, losable). I write at high speed, and not infrequently in manic twelve-hour sessions, because once I’m in a poem I fear that a night’s sleep will make it lost to me. The 4-way pen is perfect because it means you can get the emerging body of the poem down in one colour, so the poem develops a form and a substance, whilst also keeping notes in another colour of all the different variant directions – alternative lines, line breaks, punctuation… – the poem might be considering. Draft pages become a beautiful colourful mosaic of words that it makes you happy to look at, and keeps you going. In this nascent stage, the poem is less like a tree growing than it is like all the roads in a busy city, cars zooming off here there and everywhere, a woman with a pram stepping onto a zebra crossing in the bottom right corner, a delivery driver changing a radio station, a man winding his window down to swear at a car ahead that’s suddenly stopped… The BiC 4-way pen is a way of mapping the poem, of letting it grow and lending some – not too much – control to its development.

For me, the pens in question are BiC 4-way multicoloured pens. I’ve arrived at them through many experiments, from 10-way Darth Vader-head pens (lovely, but cumbersome) to my father’s elaborate and super-expensive prize fountain pen (lovely but, I found to my horror, losable). I write at high speed, and not infrequently in manic twelve-hour sessions, because once I’m in a poem I fear that a night’s sleep will make it lost to me. The 4-way pen is perfect because it means you can get the emerging body of the poem down in one colour, so the poem develops a form and a substance, whilst also keeping notes in another colour of all the different variant directions – alternative lines, line breaks, punctuation… – the poem might be considering. Draft pages become a beautiful colourful mosaic of words that it makes you happy to look at, and keeps you going. In this nascent stage, the poem is less like a tree growing than it is like all the roads in a busy city, cars zooming off here there and everywhere, a woman with a pram stepping onto a zebra crossing in the bottom right corner, a delivery driver changing a radio station, a man winding his window down to swear at a car ahead that’s suddenly stopped… The BiC 4-way pen is a way of mapping the poem, of letting it grow and lending some – not too much – control to its development.

If Tarantino is an uncelebrated expert in stationery, he is also keen on drawers. In the same interview I’ve already discussed, he talked about being convinced that certain pages of his screenplay were no good, and putting them away in a drawer. Six months later, he opened the drawer to look at the pages again, and realised that the film couldn’t live without them. That process – of writing until you know what you’re writing is rubbish, then putting it in a drawer – is crucial for me. It sounds odd to describe a drawer as the co-author of a poetry collection, but this is essentially the case. Poem after poem has been put into the magic drawer in a state of being no good at all, and has emerged six months later as book-ready. What the drawer does to them or how it manages it I have no idea. Of course it doesn’t always work, and sometimes things you thought were promising emerge from the drawer in a state of shambles or, much worse, looking simply limp and tedious. But either way, the drawer has spoken, and its judgements are unquestionable. I suppose the drawer you use might be important. I use this one. Here.

The third key component in crafting My Family and Other Superheroes was places. Just as my mother might make a pencil sketch of a scene while out and about before going home and reaching for the watercolours, the oils, so I tend to write the beginnings of poems in cafés, on hillsides, in museums, in front of animal enclosures at the zoo, while staring out at my terraced street. If it goes well, there is something about the energy of the place and the people which takes over and writes the poem for you. Here’s the opening of ‘View of Valleys High Street through a Café Window,’ which was written while sitting in the window of the old Starbucks in the Westgate building in Newport:

Out there, policemen in attention-seeking

fluoro-vests eye up a single mam

pushing a pram, her head down and her face

so much a frown, it’s like she’s trying to mow

the pavement.

My father’s second least favourite thing, after lost fountain pens, is people who don’t write thank you cards for gifts received. I say this not just as a subtle hint to any family members who are reading this and find their next Christmas present under threat, but also because this seems like an opportune moment to repeat some important thank yous. As far as poetry goes, ‘How I Wrote’ is always about the people who helped you write. For me, a Literature Wales New Writer’s Bursary was a lifesaver. It was enormously productive, both in terms of the poems I wrote during that period – which included key poems in the collection, such as ‘Anatomy’ – and in terms of the six months following the bursary period, when I wrote in a way that was far more prolific than I ever had, and generated a large amount of the material for the book. Most importantly, being obsessed with writing poems, and the constant process of having work rejected, can lead to completely insane ways of living your life, and the external validation of support from Literature Wales was crucial. Similarly, receiving the Terry Hetherington Award in 2010 and the people it allowed me to meet, the access to a writing community and the ongoing support that the award’s organisers give, has been crucial. In the run-up to publication, I was convinced that the book was embarrassingly bad, and was set to try and delay or cancel its publication. It was only incredibly thoughtful and generous letters from my university tutors which made me think that it would be okay. Without the help of these people and organisations, My Family and Other Superheroes would not exist in the form it does.

That non-existence offers a decent jumping-off point into the last thing I’d like to say, which is this: I wrote by not writing. I remember Jamie Carragher after his retirement from football talking about the extreme lows that losing a football match generated for him – so much so that it often made him think of giving up. There were many days – most days, in fact – when I was convinced I was done with writing, that I couldn’t write, that I’d never been able to. Half an hour later I’d find myself writing the best thing I thought I’d ever written. I’d like to say I’ve come to trust the absence of creativity as being a necessary part of the upswing into creativity, but have I hell. Not writing is utterly terrible – it makes you, incredibly quickly, a shrivelled and broken creature – but without it, it seems, you can’t have the magic.

I’d also like to talk about not-writing in terms of the poems I’ve written which no one will ever see. I’d like to say I throw away 99% of what I write but I am not so successful. I honestly think that about a thousand poems are begun for each one that survives. Many of these are worked through a large number of drafts to a strong stage of completion. I think so much about a poet depends upon their taste, what work they choose to preserve and what they throw away. I was asked a couple of weeks ago about the use of humour in my work and I talked about the influence of James Tate, Charles Simic, Thomas Lux and Simon Armitage in forming my voice, all of which is true. But when I think about why my poems which survive do survive, there’s one answer: they brought me joy. They were written in a thousand different ways. Some popped into my head while out walking, and had emerged fully formed by the time I got home to write them down. Others took weeks and weeks of crafting, re-drafting, thinking about the form. Others I’d given up on, stormed out on, told them to sod right off, only to find them tapping me on the shoulder weeks later when I was washing the car or standing in a school assembly, whispering my name. But all of them which survived made me smile and giggle as they announced themselves, made me ecstatic as they spread out in every direction and shouted their possibilities, as they shouted themselves. Ultimately, they made me deeply, deeply happy. This is the only yardstick I have or trust, and I suspect this is why the humour in the poems ends up being there.

I’ll give the last word to a poem which did this, which is the closest thing to a poetic manifesto I have, and which says much more articulate things about ‘How I Wrote’ than this article can. It’s written from the point of view of the front-of-house guy in a restaurant, who spends his life trying to control an insanely creative and unreliable chef. It was inspired by watching an especially bad sub-Masterchef programme a few years ago, in which the ex-Liverpool goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar was actually a contestant. I think I’m correct in remembering that he wore a white hat. The poem is really all about the process of writing of course. I’ll leave you here now with it, because I’m away down to WH Smith. By the time you get to the last line, I’ll probably be gazing up at the lines of BiC 4-way pens there, those magic wands, those inky demons. Perhaps I’ll be hearing something, over there in the distance – a couple of sounds, a couple of words, I can almost make out. A bit of a breeze. The start of something.

Restaurant where I am the Maître d’ and the Chef is my Unconscious

I put through an order for spaghetti aglio e olio.

He sends out a soup bowl full of blue emulsion.

A regular asks for lamb shank with rosemary.

Out comes a beetroot served with a corkscrew.

Someone I suspect of being a restaurant reviewer

orders the baked rum and chocolate pudding.

A mermaid rides a horse out of the kitchen.

He locks himself in there for days.

All I get are incoherent mumblings,

often in French. Some nights after closing time,

we sit down together with a glass or two,

get on famously, see eye-to-eye.

Next day he sits in a deck chair all through service,

wearing a paper hat and a tie-dyed surplice.

‘That’s it,’ I say, ‘I’m speaking to the owner.’

That night he shakes me awake,

takes the lid off a serving dish:

an actual star he’s taken out of the sky

and put on a plate. I know it’s only a dream,

but next evening I’m bright and early at the restaurant,

shouting the orders, shaking the customers’ hands,

picking bits of gold out of my teeth.