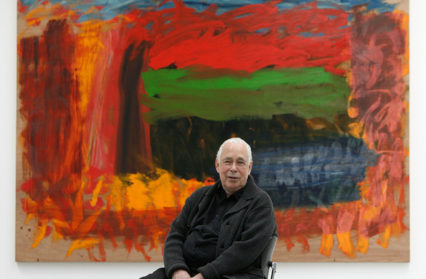

Adam Somerset remembers Howard Hodgkin in his own words.

Howard Hodgkin died 9th March aged 84. The obituaries followed the ascent from Camberwell School of Art to CBE in 1976, knighthood in 1992 and Companion of Honour in 2003. Trusteeships of the Tate and the National Gallery accompanied honorary fellowships and doctorates. None were quite so sharp as the review that Robert Hughes wrote during his time as art critic for Time. He pointed to a key moment in Hodgkin’s childhood, a visit to Margery, the sister of Roger Fry. Her house was filled with brightly coloured furniture from the Omega Workshop. Hughes summation of Hodgkin was “there is not a more educated painter alive, and it would be hard to think of one whose erudition was more exactly placed at the disposal of feeling.”

Hodgkin appeared as one of a series of eminent artists in conversation with John Tusa in 2000. The series was broadcast on Radio 3 and Hodgkin spoke across a range of topics.

On physical effort

It’s physically very difficult with very large pictures because the necessity of making the kinds of marks I do and the necessary technique for making them requires considerable stamina.

On marks and strokes

I say “marks” deliberately. Because a brush stroke suggests something that is a sort of free fall, and of course it’s not. It’s made with a lot of deliberation, which I cannot describe. They’re made to look like a very free gesture, but it very rarely is.

On layering of paint

I work and work and work until the picture’s finished, but I always work on top of what went before. When I began. I used to occasionally wipe it all off, but I don’t do that any more…For me, emotionally or even intellectually, one thing leads to another, so that- as I did once or twice, many years ago- if I try obliterating it by removing it, one thing doesn’t lead to another. You have to start totally afresh.

On gradualness

I am a very regular worker in the studio. But I often sit in my studio, apparently doing nothing at all. Because sitting with what I’m working on…by sitting looking at a painting for a very long time rather than keeping it away from me and then returning to it, I can work on it more quickly.

On the specific in abstraction

I always begin with a very firm- or rather very exact- visual memory. But I wouldn’t now feel it necessary to put it all down. I might just put down a part of it..But it has to be visual.

On the classical in art

I try to make pictures, which are sort of inviolable physical objects. They stand up by themselves. They absolutely can’t be changed, they’re unambiguous. Few people would agree with that. And they are containers for very strong emotions. When I look at a painting by Poussin, for example, I see just that. When I look at a painting by Seurat. I see just that. They’re monuments which defy time.

On the loneliness of the artist

The older I get and the longer I work, I sometimes think I am dragging behind me an enormous weight, a sort of bag of all the loneliness I’d felt in the past. It can become very oppressive and I envy, quite literally, the kind of artists who do not do their work themselves.

On rest

I find it almost impossible to stop working. My friend Patrick Caulfield said “Painters are always working.” And in a curious way, I think it’s true. When I was very young I thought one year I will take off a complete year, but I never have. And I suppose, now that I’ve grown so old, I think there’s no time. Because there is a moment when one thinks there’s endless time and then, of course,there isn’t.

On artists talking about their work

I don’t find it easy. I think that words are often extraneous to what I do, but I work in a country where words seem to be paramount as a form of communication and I think that if I didn’t talk about my work at all, people might not even bother to look at it at all.

In New York…people would come and talk to me about my pictures, but they understood exactly what they were all about. They would tell me about the feelings that they evoked in them.