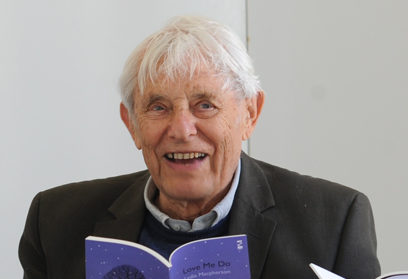

Dannie Abse has produced a body of work with few parallels in Welsh Literature, at least in terms of its sustained levels of high quality poetry and prose across a career spanning six decades. In this, his ninetieth year, his latest volume of poems Speak, Old Parrot is published by Hutchison. Wales Arts Review caught up with him as he prepared to give a poetry reading, accompanied by students from the University of South Wales, as part of the Caerleon Arts Festival. Love, loss and memory are constant and prominent themes in Abse’s work, so I began by asking him about his brothers; Leo the campaigning Labour MP and social reformer, and Wilfred, the eminent psychiatrist.

PM: One striking aspect of your writing is the intersection between the political and the personal, and you once spoke about your house being filled with Marx and Freud…

Dannie Abse: When I was a child, yes.

To what extent do you, as a writer, owe a debt to your brothers?

Dannie Abse: I’m immensely indebted to both Wilfred and Leo for the very reason that I was listening to the adult conversation of the nineteen-thirties when I was just a schoolboy. I was hearing about unemployment in the Welsh valleys, about the war in Spain and all this was particularly interesting because I went to school in Cardiff, to a Catholic school where they were pro-Franco. So you know there’s nothing like being angry if you’re in a minority of one in a school.

You once said ‘I have two roots; that of Dafydd and of David.’ Are there times when you feel more Jewish than Welsh, or more Welsh than Jewish, how do you reconcile the two halves of your identity?

Dannie Abse: If somebody is talking about Israel, I certainly feel more Jewish at that moment. There are certain occasions, of course there are, when someone is being anti-Semitic – then I feel yes I am a Jew. And I have said before, I think quoting somebody else, ‘I’m a Jew as long as there’s one anti-Semite alive.’

For me, particularly in your early work, there’s a palpable sense of Welsh lyricism, and I wondered what aspect of your writing you consider to have derived from your Jewish ancestry.

Dannie Abse: When I was writing Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve I was interested in contrasting colloquial dialogue with a more rhetorical and poetical form of prose. And somebody said to me you should read Dylan Thomas’ Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, and I read that and I got very worried because I thought – he was very famous at the time and here I am writing my first novel – he’s done it! There were so many commonalities; the Welsh background, the seaside settings and the similar poetic language. Then I realised that there were two things that were not in Thomas’ book; he was not Jewish and there were no politics at all. Therefore, I thought it would be useful to stress those aspects quite particularly in Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve. I wanted to bring in the whole world and scream about the war that was going on in Spain, as it does in that book. So Dylan Thomas had an influence on me, negatively, I wanted to avoid being too much like him.

In one of your early poems ‘The Red Balloon’, a child’s balloon signifies a young boy’s Jewish identity and then becomes the target of anti-Semitic abuse from other children. It put me in mind of Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve, that sense of childhood innocence being punctured by the outside world encroaching in…

Dannie Abse: Yes that’s true…

Which I think is one of the best qualities of the book.

Dannie Abse: Yes, you’re right because when I go back to Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve, at the end of book the outside world enters into the personal world with the death of Keith.

I know that book isn’t strictly autobiographical, but was the character of Keith based on any one particular person?

Dannie Abse: No, I used the names of the people that I knew and put them into situations that they could have been in, but weren’t. And this led to two things, first of all my mother saying things like, ‘Dannie, do you remember that fight between your Uncle Bertie and Killer Williams?’ I’d tell her, ‘Mother that didn’t happen.’ She’d say ‘Yes it did, of course it did,’ very indignant, you know? So sometimes you change people’s memories. The second thing is that when Penguin published Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve I was horrified to see it was classified as an autobiography. That’s led to an awful lot of problems for me over the years. People have come up to me, after reading that book, saying, ‘I’ve read your autobiography,’ when in fact my actual autobiography is Goodbye Twentieth Century. And it’s a shame really, because I want people to read the autobiography that is actually my autobiography, and read Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve as a novel, because it is a novel.

Perhaps people mistake it for autobiography because it is suffused with such a profound yearning for a lost childhood. I was surprised to note that you were quite young when you wrote that book, it read to me like an older man’s recollection of a distant past.

Dannie Abse: Ash on an Old Man’s Sleeve?

Well yes, it has such an elegiac tone, a sense of loss of youth, and a Cardiff that had gone, and yet you wrote it just after the war.

Dannie Abse: It was probably easier to write then. I couldn’t write it now. I wouldn’t have so many adjectives in it for a start. I did write another book, There was a Young Man in Cardiff, which I think in many ways is a much better written book.

Why do you think it is, that a book becomes attached to its writer – even comes to define that writer’s career – as their key work, when it’s not always their best book?

Dannie Abse: Well, Ash on a Young Man’s Sleeve is certainly my most successful book. I suppose lots of people have read it. Lately, it’s been a book I wrote when I lost my wife. It seems to be happening in the same sort of way. That book is called The Presence and it’s about personal loss and how I responded to that loss. I survived a car crash, my wife didn’t. And I didn’t really write it initially for publication. It was a therapy for me in some ways and I was persuaded to go on and for it to be published. And I’m glad because I can’t tell you how many letters I’ve had by people who have lost their parents, lost their wives or husbands. Or even people that have been divorced. Everybody has had a loss and they seem to have drawn something from that book.

Some of your poems that I most admire are on the subject of marriage. You write so movingly about enduring love. So many poets write well about wooing and courtship, they get as far as the altar and no further. But you chose to write about the love that emerges after – how love within a marriage has to mutate or evolve into a different form of love, but which is just as profound.

Dannie Abse: Have you read Two for Joy? That’s my love poems written before, during and after really.

I would argue that the poems you wrote after your wife’s death are your best. Would you agree, or is that experience just too close for you to assess them in that way?

Dannie Abse: I certainly have attracted more public attention in my latter career but that doesn’t mean much, I mean in terms of whether The Presence is good or bad. There are all sorts of reasons why people get attention. I’ve certainly won a lot of prizes in recent years. But poems aren’t in competition with each other, poets are in competition with each other, but not poems – and one’s own poems are not in competition with each other. If I did another collection of my poetry right now, before I go, there would be certain poems I wouldn’t like to revise or certain poems I would drop because I think they didn’t work. But there are quite a lot of them that I would keep.

In your poem ‘Just a Moment’ you write, ‘a poet’s late adagios/like those of Beethoven Adagios (Muss es sein?)/should say more about the seasons of fate/than the years have wings and the hours pass.’ It seems to me that you have achieved exactly that in your later work. You explore old age but not in any clichéd terms, you have found some form of wisdom.

Dannie Abse: I think it was TS Eliot who wrote, ‘Do not let me hear/Of the wisdom of old men, but rather of their folly.’ I don’t know. I write what I can. One of the things I’ve always felt I have said, and I’ll say it again, is poetry is not an escape into reality but an emotion into reality. That’s why earlier on in my writing career I felt I had to confront my most dramatic, traumatic, medical experiences. And now I must face the fact that I am old. You know it’s hard to say you’re old? People don’t like to say it, it’s as if it’s like having a disease and indeed very often old people complain about being invisible, and it’s true.

Can we talk about your poem ‘Carnal Knowledge’?

Dannie Abse: I’m very pleased with that poem. It came from my early experiences as a medical student during the war, so in a sense it relates to Wordsworth’s definition of poetry as emotion recollected in tranquillity.

It’s not a tranquil poem, it’s very unsettling.

Dannie Abse: Oh, it is an unsettling poem. One interesting thing about it for me, which I still can’t get over, is that I once received a letter from Stephen Spender claiming that I had made a mistake in the poem. He wrote that in Schubert’s Quintet there should only be two cellos, and of course there are only two cellos in that quintet, that’s the whole point – the third cello is the one played by death. So even somebody who, poetry-wise, was sophisticated doesn’t always understand what you’re getting at.

That poem haunted me for ages. The manner in which you convey the intimacy of the post-mortem examination – the intimate contact with the inside of the body and its organs – is very powerful, yet restrained. What kind of poet might you have been if you hadn’t been a doctor?

Dannie Abse: My career as a doctor was spent mainly in a chest clinic. I’m not sure I was really fit for medicine in many ways, and I don’t think poets are. They’re supposed to have empathy for people. It’s disastrous for a doctor to have too much empathy and that was a serious problem for me.

You referred to the ‘negative’ influence of Dylan Thomas on your early work. How do you assess his legacy today as we approach his centenary?

Dannie Abse: Well I still find his best poems thrilling, actually. He had such a wonderful ear. He did have his limitations as a poet but I think that for some of his poems one should be willing to shine his shoes.

In your two poems about Thomas, there is clearly great respect for his work, but there is also the sense that you regard him as a cautionary figure.

Dannie Abse: He committed a form of suicide and I don’t think that was a good idea. One of the most interesting things to note about Dylan was that he discovered in performing his poems how to communicate with an audience through achieving greater clarity in his verse – as he gave more recitals his poetry became more clear, and I think some of his best poems are a consequence of his being exposed to audiences, and having to make himself clear to them, not out of courtesy but because he wanted the applause of the crowd. Although I don’t think he did this consciously.

In contrast to Dylan Thomas, and other writers who fall victim to a certain romantic ideal of being a poet, you’ve built a – how can I put this – more steady and sustained career. You’ve been working away for six decades now…

Dannie Abse: Well I didn’t have a choice. I’ve always said if I stopped writing I’ll die. At the moment I’m pleased with my latest book.

Your commitment to writing well into your eighties is an inspiration. But you don’t see it as a commitment do you?

Dannie Abse: I’m committed to make the best poem I can with what gift I have – to make it the best poem, that’s the commitment. I don’t think you have a choice, you either need to write or you don’t. I once took a year out of medicine, to be a writer-in-residence at Princeton University. That was a very agreeable year for me, I only had to work one and a half days a week.

What did you learn from your students during that time?

Dannie Abse: That’s a good question. Well, I learned that a lot of people find it hard to write. Well you must know that there’s quite a lot of group therapy in these things going on. So I sometimes felt like I was also behaving like a doctor sometimes.

You’re appearing later at the Caerleon Arts Festival, and I wanted to ask you a question about your poem ‘At Caerleon’. In that poem you visit the remains of the Roman Amphitheatre, but the visit is disturbed by the arrival of a group of boorish, drunken, young males. Finally they leave and you write that you, ‘sit down and play/ (paper on a comb) mournful tune/from an imagined country/that would break an exile’s heart.’ Where, or what, is that imagined country?

Dannie Abse: Well, I don’t think I should name it really, but I’ll tell you a story… The Chinese were at war with the Mongols, who were laying siege to one of their cities. The Chinese general charged with defending the city had lost all hope. All the food in the city had been eaten, they had no water – he saw clearly that he had no choice but to surrender in the morning, whereby the city would be sacked and women would be raped. That night he climbed onto the battlements and ordered a musician from the city to play a lament. The musician happens to play an old Mongol tune. The besieging Mongols come out of their tents; they listen and become so nostalgic for their homeland that they pack up their tents and go. That’s my tune from an imagined country.

Do you have an assessment of Welsh literature right now? Are there any Welsh writers that are coming through that impress you?

Dannie Abse: I’m less interested in other people’s poetry in general now. Every now and again I go back to people I really like and from the past. People send me poems. I hate that. Sometimes they write and ask if they can and I decline.

Because you would then feel obliged to pass comment?

Dannie Abse: Yes. And I’m not an editor. I sometimes think of how generous other writers I know have been. I love the story about Chekhov, who, when he was young, used to write a column of short humorous sketches for a Moscow newspaper. He didn’t publish them under his own name. One day he got a letter, quite out of the blue, from Dmitri Grigorovich, who was one of the most popular Russians novelists of the day. He told Chekhov, ‘I very much like your stories and you should write them under your own name.’ I wish I could be generous in that way but I’m not.

Well, there’s other ways of being generous – what you shared with your readers in The Presence is a form of generosity, which, as you say, was acknowledged by all those letters your received.

Dannie Abse: Yes I hope so. Anyway, I think as you get old – I’m eighty-nine – you have to look after yourself.

For which of your works would you most like to be remembered?

Dannie Abse: I suppose a selection of my collected poems, but not my Selected Poetry because there are a few poems that I would add now.

Even at eighty-nine there are new poems you wish to add, poems you are yet to write?

Dannie Abse: My Selected Poetry was published nearly ten years ago. And I’ve written quite a lot of books since.

Your recent poems have a kind of simplicity that is very difficult to pull off. I think you have to write for a long time to find that level of simplicity.

Dannie Abse: Which also has a layer?

Exactly, a deceptive simplicity. There are quiet surprises in these poems, phrases linger, and you realise you haven’t fully grasped what they mean…

Dannie Abse: That’s one of the things I always put on the blackboard, when I first went to Princeton, ‘Find the most surprising yet appropriate word.’ To give one obvious example, you know you could describe trees as green, well that’s not surprising, but if you used a word like ‘clockwork’ to describe trees then it would be surprising but not appropriate, so you have to find one that’s both. If you ask me what I’ve strived for in my writing it’s finding this combination of the surprising and authentic. Perhaps I didn’t when I first started, but in the last I don’t know how many years…

Abse’s voice trails off and he places a hand gently over my digital recorder. ‘I’m thirsty’, he says quietly, ‘I’ve been speaking for too long’. I fail to understand at first because, even at his advanced age, it is clear that he has so much more to say, about his recent poems and those poems yet to be written. Then I remember he is to give a reading later and requires a little time to rest his voice and prepare. My overall impression of Abse is fixed in this moment; a man carefully husbanding his energies in old age so that he is able to continue to mine the depth and richness of his own experience for the illumination of others.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis

Photo credit: licensed by Daisyheadmaisie

You might also like…

There Was a Young Man From Cardiff is certainly a personal narrative. The total text tells the story of one man’s life, though each individual narrative portrays wider concerns of the world. Each of these narratives is in some way a part of the landscape of Wales, and despite the changes he perceives in his country, it is always a solid part of Dannie Abse’s life.

Phil Morris is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.