The documentary photographer David Hurn is what might be termed, ‘an accidental Englishman’ – born in Redhill to Welsh parents, after a childhood in Wales, he travelled the world, radiating out from London to Hungary, the Mediterranean coast and the USA. What distinguished these journeys and defined them was the Leica camera he carried with him and his work as a freelance photojournalist. In 1970 he returned to Wales and, due perhaps to his prodigal status, he set about discovering ‘the land of his father’ in the way he knew best, through photography. A member of the legendary photographic agency Magnum, Hurn’s personal history is also a representation of history with a capital H. From Aberfan to the Beatles, to film stars like Julie Christie and Jane Fonda, from protest in Grosvenor Square to revolt in Budapest, to the sublime light and shadow of Tintern Forest, to miners, steel workers and sheep farmers, Hurn’s photographs have held a mirror to history, revealing both the World and the Welsh nation and fixed them in time as documents of extraordinary truth.

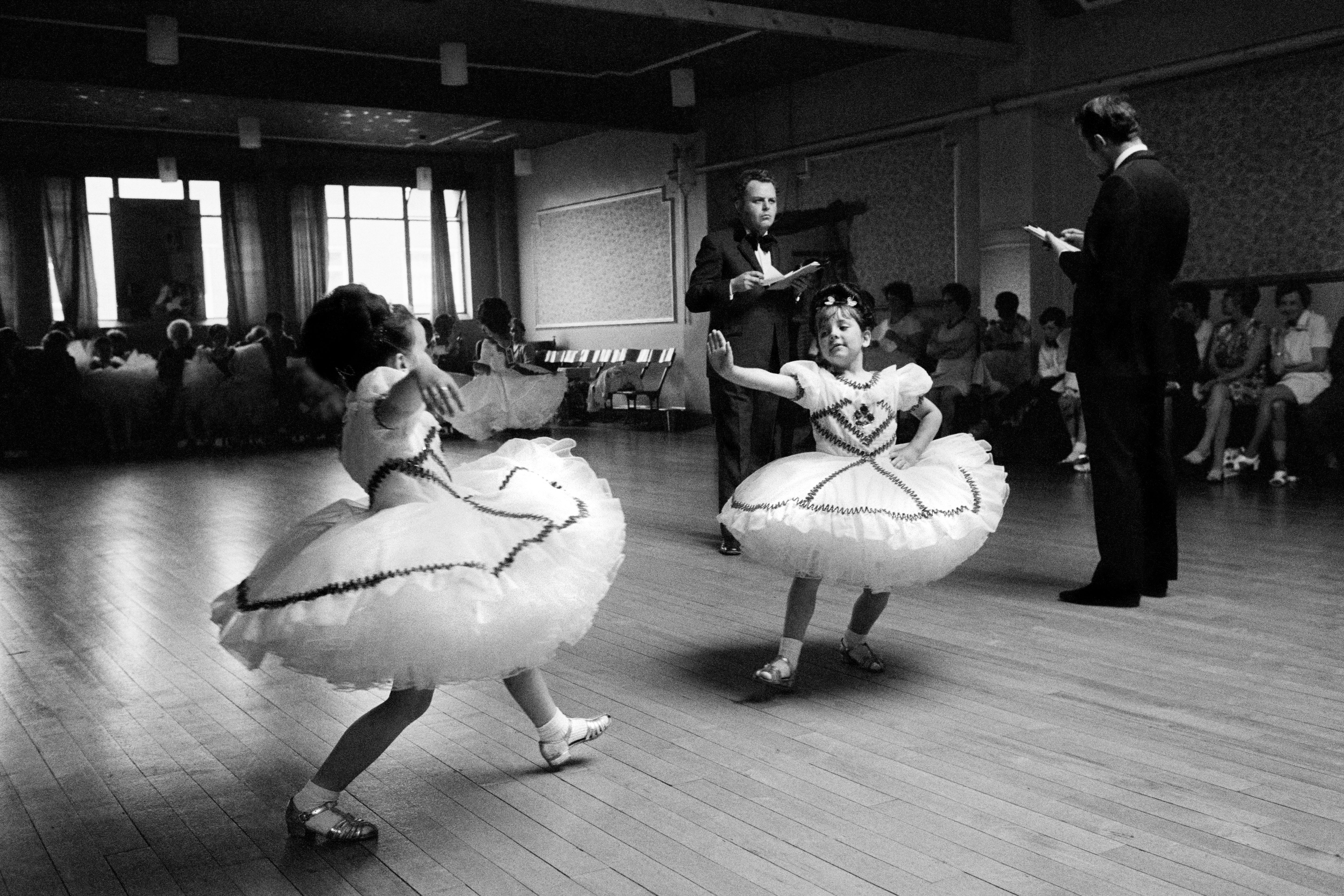

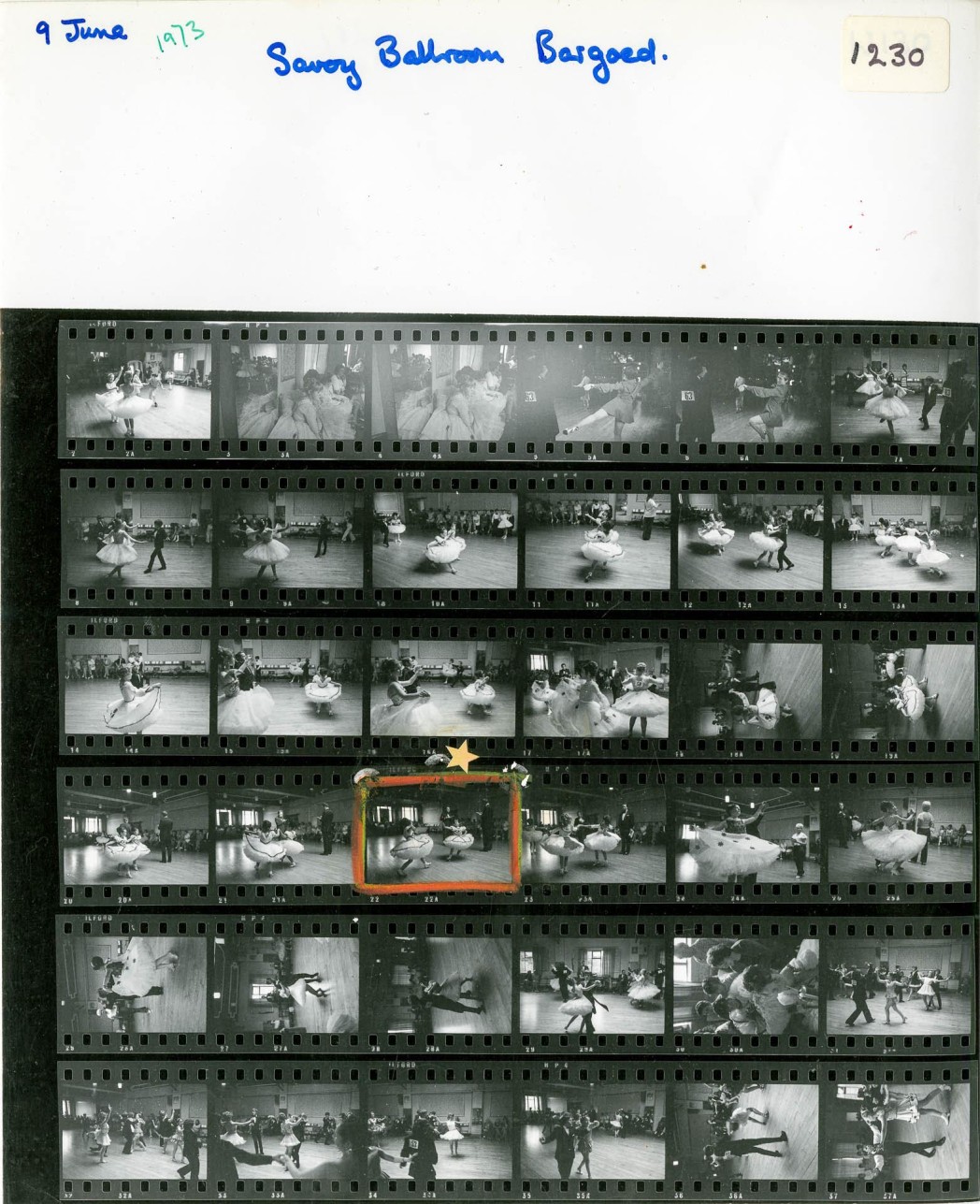

As a documentary photographer you record what you describe as ‘Things as they are’ – putting aside the choices you make when you are shooting photographs, I assume that several rolls of film may result in perhaps only one print. Looking at ‘Junior Ballroom Dancing Championships, Bargoed, 1973’ I am struck by the perfect doll-like symmetry of the two girls in frothy matching dresses and how it is echoed by the two formally dressed men who stand facing one another, papers in hand, forming an arch over one girl, but seemingly not at all interested in the children’s performance. It creates a slightly surreal effect as well as a graphic one. How many pictures did you take before you found that one?

I always tend, when I go to shoot pictures, to approach it almost as though I am doing a news story so I am very aware of shooting at various distances, because my early upbringing in photography was working for magazines and newspapers and there, part of the trick of getting into these places was to do something they could lay out as a set of pictures. But I always find it very easy to work in terms of close up pictures, middle distance, long distance pictures. So in other words things that I am doing I always tend to do as three. On something like that image my guess is that I probably shot four or five frames. At that time because it was shot on film – four or five rolls – because I would have been covering the whole of the event. The two standing men are judges – they’re in dinner jackets – I mean the whole thing is wonderful in that everyone goes to that much trouble, but it is slightly surreal. And so what one is trying to do is to capture that very authentic moment that somehow sums up the whole of the thing.

Most of the time you go along, and it’s all okay, it’s a record of what was there. But there’s that thing about photography – it must be the only form of communication which by definition gets better as it gets older – simply because it becomes historic. Because a photograph has that trace link to a real moment in time it always gains in value – so the trick is to make sure the particular trace that you get is also in itself significant. Then you hope that in a hundred years time it also has significance because it’s about a moment which was significant.

And that’s what I think that the best photographers are attempting to do. They don’t do it that often – it’s terribly, terribly difficult – with photography you have a mess which instantaneously you are trying to make into some sort of formal statement and if you don’t get it that’s it.

Like many young people in the decade following the Second World War you went to London in the 1950s, how important was that to you?

When I came out of the army I went and worked in Harrods and I would go and shoot pictures every evening in the places I went to which, by and large, because I don’t drink, were coffee bars. It was the great era of coffee bars and a lot of skiffle music and so on was starting in those coffee bars around Soho and the ones that I went to; one called The Nucleus, another called The Partisan, were leftwing meeting places. I discovered there – what we now call networking – that if you had real enthusiasm for something and really did something, it was amazing how people tended to gravitate together. So in that 60’s period, or rather the mid-50’s, I don’t think it’s at all a coincidence that groups of people became friends and they were people that did things. They tended to become friends because they were drawn to the people that seemed to talk passionately about something and did it. One of the people that I met, for example, was Colin Wilson, a writer who at that time spent his nights in a sleeping bag on Hampstead Heath – he hadn’t yet written his book The Outsiders, and Peter Everett and Stuart Holroyd – were all people just hanging around in the coffee bars. One of the people who was there quite a lot was Michael Foot who at that time was working for the New Statesman and was brilliant. Another friend I made there was the film director Ken Russell. I was also very friendly with a guy who was later to become a very fine writer, John Antrobus, who worked at times with Spike Milligan, and also wrote some of the Goon Shows when Spike was ill.

One of your earliest successes were your photographs of the Hungarian uprising in 1956 – your career might have taken the same path as Don McCullin’s – photographing war and strife – was it chance or choice that you went another way?

Very much choice. In the coffee bars there was very much a political climate and about that time, when I was feeling my way as to what I wanted to do, suddenly the Hungarian revolution looked as though it was about to happen. So myself and John Antrobus decided, bizarrely – but then I was 21 – that we should hitchhike to Hungary. So off we went, and we got to Austria and by chance met up with ambulances that were going in and got a lift in one of them.

So I arrived there and again I had very good instincts. Although I didn’t know what I was doing – I found that the problem with being in a war situation was that it was different to how one would imagine, with it all happening all the time. It’s not like that – events come and go – so it’s very easy to be sitting in one street drinking coffee and they are all hitting the hell out of each other in the next street and you don’t even know it’s happening. I was sensible enough then to realise that I needed to attach myself to the best journalists because they would know where to go. And I guess instinctively, and I later discovered this was true, I found that the journalists tend to congregate in one place – stay in the same hotel – and so I found this hotel and it happened that reporters from Life magazine – who were as good as any in the world – were there but at that time they didn’t have a photographer. Because the photographer hadn’t got into the country – and so they grabbed me and I went around with them. Therefore much of the stuff I got in Hungary came about because I was sensible enough to subdue myself to the reporter – I let them do the work and I took pictures – which is not that difficult if you are there. The difficulty is to get there. Then they got me out which was quite difficult given the circumstances. So the pictures were published in Life magazine and also the Picture Post and The Observer. I discovered that a good place to start is at the top. So that’s how that came about.

Now at the time we’re talking – most of the work was in newspapers, which at the time were very good. I mean the Daily Express used to run big double page pictures. I think I’m right in saying that The Daily Mail at that time had 32 foreign correspondents – I mean it was serious – not like the bloody damn Daily Mail today which is like a fantasy rag.

So one shot pictures and tried to do what was called current affairs which was a newsy thing – which wasn’t really me. My contemporaries were people like Don McCullin, Philip Jones Griffiths, Ian Berry and John Bulmer… but they were all very much linked to that newsy, current affairs type of thing and I wasn’t. I was much more interested in, what McCullin said of me, ‘a tinsel society’ which is really – my idea of bliss – a sheepdog trial – everyday happenings – what ordinary people do. I was never that interested in the exotic – when I was doing the exotic I was always going to be second best to photographers like them because they were passionate about it – you know McCullin was interested in anything that made his adrenaline go. Philip Jones Griffiths was a very astute political animal – he really understood what politics were about – there was no way I was going to compete. Yet because of the market I was finding myself having to compete, which I understood, but it was difficult. Then the colour supplements started and it became the opposite with me because there were a whole lot of photographers doing current affairs but there was virtually nobody that wanted to do the sheepdog trials or the Ballroom Dancing Championships and so I suddenly had a niche and from then on I was away. It sounds pompous but I had no competition.

I think I read or heard your pictures referred to as always being humane.

Well I hope so! But what’s the opposite?

Well, Diane Arbus I suppose would be the opposite…

Ah, I knew Diane very well. I suppose my pictures are in that French humanistic tradition – you know – touchy feely etc.

No, but not to the point of being…

No, not sentimental but I do tend to look for the best in life – I happen to think that the world is a wonderful place, I’m really pleased that I’m here and I’m certainly not going to wander through the world looking for the crap and then worrying about it, particularly when experience tells me that you can do nothing about it.

Yours is one of the iconic photographs of the Aberfan disaster. Two boys stand in the foreground with the destroyed school before them. It creates a narrative that suggests these boys are survivors, reminding the viewer of the youth of those lost. How hard is it to remain professional and still act as a witness and messenger at a tragic event like this?

It was a very significant event for me. Cardiff is my home town but because I had gone to boarding school (due to the fact my father was in the army and moved around a lot) I’d gone straight from there into the army and then straight to London, so I hadn’t gone back to Wales much, although we’d always had a home in Cardiff. I happened to be in Bristol when I heard about Aberfan on the radio and I was with Ian Berry, a photographer friend of mine and so we turned around and drove straight to Aberfan, getting there in the afternoon. Of course, how can anything be more obscene than kids being suffocated by coal crap. It was extremely tense, because what you had was miners digging, looking for bodies. By and large, very understandably, they didn’t want you there. Against that, if you are a photographer, you build up this thing in your mind of saying, my job is to record for history. I tend to always come down on the side of that; simply because I think when people say you can’t record they’ve normally got something to hide. So my excuse always for going into somewhere that is tense and recording it is because I know that if it was essential I could destroy the stuff afterwards.

I know in that sort of circumstance it was very important that it was recorded – what actually happened – and also that this was the ultimate in sensitivity – so it was that balance between the tension of knowing that they didn’t want you there and the tension of you knowing that you had to be there – that was the justification for being a photographer and at the same time trying to be sensitive. It turned out afterwards that my pictures were published all over the world and there’s no doubt that it contributed a lot towards money coming in for the disaster fund and so I got quite a lot of letters later – you know – people thanking me.

So in the end you realise that actually you had done the right thing. I think it was done sensitively. But it was that that made me think that I wanted to come back to Wales. That was 1966 but I didn’t actually come back to Wales until 1970. But it put the seed into my mind that I wanted to come back. And, of course, I’ve been here ever since. And I think primarily fifty per cent of my time since then has been spent recording Wales.

But Aberfan was an extraordinary moment for me; it just affected my whole life because it was obscene. It was not necessary, and you suddenly realise the greed of individuals involved, from government to private; everything about it was to do with how much money you could make out of something and not really think about the consequences of safety.

The image of a model skeleton on the porch of a wooden house is incredibly creepy – how did that image come about?

I got an American Fellowship; the bicentennial fellowship award that paid for me to go to America for a year to work. So I chose Arizona, because a, it’s the most right wing state in America and I thought it would be fun going from a place which is pretty left wing i.e. Wales and obviously Wales is very wet and Arizona is the driest state in America. So I quite liked the idea of the opposition between the two places.

What I love about Americans is they have no fear of exaggeration.

In 1979 the Arts Council published a monograph of your work from 1956 to 1976. One of the pictures is captioned Teenage Drug Addict. I have always found that a startling picture because it’s such an intimate and grim act, and also because it was taken in Swansea, my home town. In this picture the light falls only where it needs to, illuminating the blonde hair, the white leg and the girl’s eloquent hands, then lastly on the white porcelain toilet with its banner of tissue paper. I assume you got permission to take the photo by promising the girl that her face would be hidden?

No, I never ask anybody for permission. In 1971 I went to Swansea University to give a lecture. I spoke to the students, afterwards I went back to one of their homes and we were literally going up the stairs and the bathroom door was open and there was this kid shooting up.

I was very interested in the idea of culture and I knew Raymond Williams and I said to him ‘I hear everybody talking about culture but I can’t find what they actually mean’ and I remember him saying, ‘It’s a very difficult word. In the British language we have only one word for culture. Most other languages have two or three or four. The problem is that in this country when you talk to somebody about their culture, half of them are talking about farmers, half of them are talking about painters and sculptors.’ So I thought, this is extraordinary, people talk about our Welsh culture, but nobody pins down what they mean by that. So the only way I could deal with that is I thought, I will wander round Wales. I will photograph the things that I think are interesting and attempt to put them together like jigsaw pieces and at the end I will see this picture like a jigsaw puzzle which is my interpretation of my Welsh culture. So that was the starting point – a part of that is the need to cover particular things – so I would list sports, I would list education, I would say eating, I would say the church, I would say the language. I would write all these things down in a notebook and one of those things was drugs. Wales like everywhere else has problems with drugs but the photographing of drugs and drug addicts is extremely difficult to do and so when I saw this by chance, I shot this. I think I’ve only got about five frames and then when I saw the film after it was developed I realised the picture was very powerful and I thought, I’ve covered that particular thing. The fact that you can’t see the face means that it didn’t enter my head about this being a problem. The problem with photography, especially if you’re shooting with film, is that you have no idea if it works until you see the negatives. The difference between seeing something three dimensional and then ending up with a two dimensional picture is phenomenal.

But you probably start to know what will work if you are using black and white.

What I know is that the situation should produce a picture, what I don’t know is whether at that moment I’m capable of pulling out that picture and I don’t know that until I see the results, but I do know that I get irritated if I’ve been in certain situations and I don’t have a picture. The camera allows me to see with intuition and spontaneity, it allows one to combine one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart. It’s all these things going together – once you’re used to it, once you have the experience, you can tell when that’s happening.

These pictures of the robbery at the jewellers are extraordinary – it’s the quality of the light and the strange garb of the criminals – so it doesn’t look quite real and in some ways it almost looks comical especially the shot of the man in the van doorway. Can you tell me how you came to take these?

This was one of these strange things – I lived in Porchester Gardens in London and I used to go around the corner to have breakfast every morning and suddenly as I came around the corner there was this smash and grab raid. I always had my camera – I never go out without my camera. So I took the photos of the victims, of the criminals getting away and the store itself as I would if I were covering a story for a magazine.

As a freelancer in the 60s how did you manage to both gain access and also get by financially?

The way I shot I would be continually saying to a magazine or something, I want to go and do this are you interested in it? Partly because one of the problems with photography is access, it’s much easier to get access if you’ve got a magazine behind you. I became very friendly with Vogue magazine and with Queen magazine and Town magazine at that time, so I’d say to them something like, I’m going to go and do Queen Charlotte’s Ball – it’s the last Queen Charlotte’s Ball, it’s the thing to with debutants and Vogue would say, fine – which meant that they would pay my expenses. I would then shoot it and then someone like Vogue would perhaps only run one picture. I would then have ten or twelve pictures that I quite liked but of course the problem is that nobody would ever see the other pictures. With the debutante’s ball they used to go and kneel to the Queen, then she stopped going so then they brought in this bloody big cake and they all used to kneel down to the cake. It was very weird – I’ve no idea why they knelt to the cake.

How did you come to take the pictures on the set of A Hard Day’s Night?

One of the people I knew from around London, as I said, was John Antrobus, he then worked for a company called Associated London Scripts which was a writers’ agency. Spike Milligan was there and Peter Sellers worked with Spike Milligan a lot. Peter Sellers did a few films for TV which were directed by Dick Lester. And so I got to know Dick Lester, then when he was directing A Hard Day’s Night he asked if would I just come and work on the film. The idea was I would work in a more general way documenting the making of the film rather than doing the stills. So I was able to capture the relationship between The Beatles and the people around them.

The 1960s: Photographed by David Hurn is published on Oct. 23rd by Reel Art Press and can be pre-ordered here: http://www.reelartpress.com/catalog/edition/69/the-1960s-photographed-by-david-hurn

Photo of David Hurn © Jo Mazelis

All other photos © David Hurn / Magnum Photos

No photograph or digital file may be reproduced, cropped or modified (digitally or otherwise), and the spirit of its caption may not be altered without prior written agreement from the photographer or a Magnum representative.