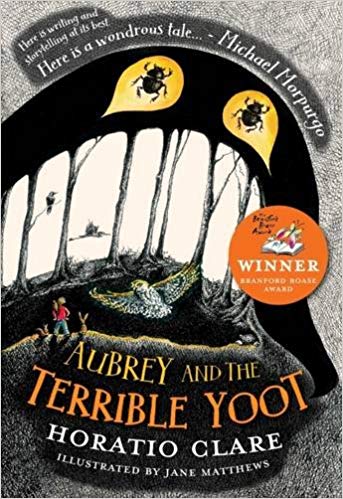

Carly Holmes sat down for a conversation with Horatio Clare, an award-winning and best-selling author of several books across a staggeringly diverse array of subjects. From his first publication, Running for the Hills (John Murray), a critically lauded memoir about his childhood on a hill farm in Wales, to his latest book, Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot (Firefly), a children’s novel which tackles complex issues with delicate, playful expertise, the vibrancy of his prose and the bravery of his writing style have attracted fans across a range of readers. Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot has recently been shortlisted for the prestigious Branford Boase Award and looks set to be a future classic in children’s literature.

Carly Holmes: You’re an incredibly versatile writer; so far you’ve published memoir, travelogue, fiction (both short fiction and novels) for adults and children, and a beautiful travel/nature hybrid that reads like poetry. Are there any genres of writing that you’d particularly like to tackle next? Can we expect a collection of poetry in the future or a horror novel?

Horatio Clare: I am going back to travel, I think, to nature/current affairs kind of travel. My wonderful friend and agent Zoe Waldie have a good phrase about good books ‘telling us something we don’t know about the modern world’. I have had this idea – after a long bleak period of coming up with ideas which did not work – about fences and frontiers, about border areas. I think I am going to travel around the edges of Europe and inspect the fences, talk to people who build and guard them, who live near them on either side, who try to cross them, and the people who vote for them and order them to be erected. A lot of frontiers are rich in wildlife – which thrives where people aren’t or can’t go – and stories, of course.

I have a love-hate relationship with borders, the romance of them, the fear, the triumph of getting through, and the obscenity of the prevention of the free movement of most people. Authority has always fascinated me, the immense power wielded by the ordinary little person in the uniform, on behalf of the suits hundreds of miles away. And if you can win that person over, or put one past him or her (I cannot remember the last time I told the truth on a visa form, like many journalists) you are pointing fingers at the invisible and heartless powers behind them, which we must all do.

And I am writing another children’s book, a follow-up to Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot.

And following on from that question, what different approaches did you have to adopt in order to write in those different styles. The Prince’s Pen (Seren), a dystopian sci-fi novel, must have required a totally different part of your writer’s brain than Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot, or Orison for A Curlew (Little Toller).

Horatio Clare: With fiction, in my limited experience, you find a character and listen to their voice, let them tell it. The narrator’s voice in all my work is pretty well the same. In non-fiction I am still working on voice, trying to be alongside the reader so that they have a companion through the journey – a feature, a book review or a travel book – but an invisible companion, not a distraction, who will not come between them and the subject, so that they travel through it as I did; I become the vehicle, is the hope, but the experiences should be theirs, not their experience of mine.

Narratives of quest or journey echo through your work, in all of the genres you write in. Are they signs of a restless temperament and a need to be unsettled in yourself in order to access inspiration? Do themes of pursuit and discovery define your deepest writing interests?

Horatio Clare: Like many of us I am torn between loving journeys and longing to take a long siesta at home – and come down in the evening for a drink and chat and fun with the people I love. I am writing this on a train from Leeds to London. Tonight I will be in a room with a runway view – hurrah! – at Heathrow, and tomorrow in Frankfurt, and the day after in Cuba, if the planes all stay up. I love it, of course. But a lot of my life is routine and not glamorous. Going to work as a teacher or a radio person or a lecturer has eaten years, decades!

I do think of life as a journey like the Odyssey, out and back again, and the journey is the best structure I know for books. Pursuit and discovery is interesting. I have quite often gone off in pursuit of something not knowing quite what it was, but trusting that the doing of the thing would yield something worth telling.

“I’m interested in the edges of things… I’d like to write about it” is a line from your memoir Truant (John Murray) when, at a particularly low point, you ponder your future career options. If writing hadn’t worked out for you (if you’d met a resounding lack of interest from publishers, for example) what do you think you would have done instead?

Horatio Clare: No question, I would have stayed at the BBC and made radio programmes (given that no chance really existed of being an Ambassador, or some sort of diplomat, which must be fantastic). I would have tried to have made the jump from producer to the reporter; part of me still wishes I could be a correspondent. How amazing would it be to be sent somewhere where things were changing in order to find out about it and tell the world? I do as many essays as I can for From Our Own Correspondent, which allows me to live that dream a little. I was very happy when I was training to be a print journalist. That would have been a rich and fascinating life if the business had not been mostly wrecked by the internet, and some too-powerful corrupt and stinking monsters. It’s a very good time to be a freelance, sadly, as most places cannot afford much staff. It’s a great job, but it’s not as fun as working with colleagues. The thing I like most about journalism is journalists, who are always interesting, mostly extremely kind and often funny.

A deep and sensitive love for the natural world resonates through your writing; a simple joy and awe that shine through even the darker moments. How much of this is a result of upbringing, or natural temperament?

Horatio Clare: Impossible to know whether I would have fallen for nature the way I did had I not been brought up with it, in all its might and blood and beauty, in Wales. I remember being very taken with the birds and fowls in London parks when I was very small, and both my parents love nature, so I guess it is mostly innate. And the wonderful thing is that writing about nature is really about writing love letters, motivated, as they are, by delight and longing and love of beauty and amazement.

Aubrey’s parents are both very open and honest about his dad’s depression, and Aubrey himself is very active in helping his dad through it, even going as far as to search for him when he’s taken an overdose. He is treated very much as a mature and valued member of the family in a book that deals with themes such as mental illness and its repercussions. How much was this approach influenced by your own attitude towards parenting, the need for openness and communication even through the most difficult of times, and do you see this as the future for children’s fiction?

Horatio Clare: Children seem extraordinarily grown up, though obviously, they may always have been so. I had nothing to do with them before 2008. But I think my generation’s parents were markedly open with us, in the second half of the last century, and therefore we are being open with our children. So children now, certainly the many lucky ones, are treated with respect for their intelligence and vision. In his book Being a Beast Charles Foster thanks his children, his ‘greatest teachers’. I thought that was brilliant. That children’s literature in this country is going through a boom, something of a golden age is much commented on. And there are lots of books which have an issue at their hearts, of course. That’s fine, but I am also in sympathy with something Amanda Craig wrote – what happened to children’s books which are pure adventure, joy and magical storytelling, not issue management in disguise? I am bearing that in mind.

Cormac McCarthy wrote The Road after the birth of his son, inspired by that fatherly love and the sense of urgency it gave to his life. What was the genesis of Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot and how much was its inception a result of your own experience of fatherhood? Would you have written it, or considered writing children’s books, before becoming a father?

Horatio Clare: I had thought about children’s books before our son was born. Because I grew up with so many, and no TV, I am much better to read in children’s than I am in adult fiction, I reckon. Actually, that’s not right – I re-read my favourites so often, the field is deep rather than wide. But before being a father I became important in the life of my partner’s son, a – then – small boy, a giant sort of teenage God these days, and so did a lot of reading aloud, and learned about children’s books again through him. I owe him a huge amount. Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot is dedicated to him. And then when our son came that was it – I had to write for him as much as about him. It gives a deep and entirely unexpected joy to write for children. It’s like finding a job you love slightly late. I had heard of similar things happening to other writers – in her forties, Sarah Dunant discovered she was a historical novelist (of astonishing power, as it happens – The Birth of Venus) having been a literary thriller writer. She is a great mentor to me and she mentioned that this change was possible, and I had my fingers crossed something might happen.

The yoot is a very sorry and sad foe, not something to be defeated or destroyed but something to be pitied, and assisted towards effecting a transition that will make its existence tolerable for all, itself included. Do you see Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot is a novel written not just for children’s entertainment but as a means to enable them to understand depression and feel less scared by mental health issues?

Horatio Clare: The odd things are I didn’t sit down thinking, right, let’s talk to children about mental health. What I thought was, this depression thing is a monster, a real monster, it would make a terrific monster for a story. And then I got myself and the book into the position of having to cope somehow with a monster that cannot be killed. The misleading thing about reading is the sense of completeness a good finished book will give. Of course, it never was, up to the very moment you finished reading it, and hopefully, closed it without feeling let down. But as you know we mostly feel our way towards whatever the book wants and needs to be in a semi-darkness, following a feeling, prodded along by illusion, more or less in the hands of the Gods and Muses.

The Prince’s Pen: Tales from the Mabinogion, and ‘The Race of Men’, the brilliant short fiction piece you wrote for the Story Retold series the Wales Arts Review have been running are both re-workings of much older, classic tales. How did you like having the template already there, laid down for you, and how did it change your approach? Did it make the writing of these two stories harder or easier than having a totally blank page and the freedom to ransack your own inspiration?

Horatio Clare: Someone else’s structure is an absolute god-send. I love Shakespeare’s professionalism: look at all these excellent plots lying around, isn’t it time someone made them work properly? The Prince’s Pen and ‘The Race of Men’ exist only because some kind and clever people in Wales asked me to write something and suggested a source or a range of sources. If I was ever stuck in future – the next time I am stuck, I mean, to be realistic – I would love to think I would have the guts and the nous to do something inspired by or based on something much greater than anything I could produce. I had a killer idea for this – you know the last scenes of Casablanca when Rick and Louis are going to have to flee together, the beginning of a beautiful friendship? They are going to Brazzaville. I’ve been there. I would love to write a novel that starts with them landing there. I’ll never dare, though.

And finally, what’s next?

Horatio Clare: Travel! And trying not to forget, however lovely the summer and autumn, that winter will come again, and it’s about time I got into the habit of laying down stores, plans and reserves, so it’s not as agonised and depressing at the last one was. (I am definitely seasonally affected. Anyone would be, between Wales, Liverpool and West Yorkshire.)

Horatio Clare is an award-winning and best-selling author of several books across a staggeringly diverse array of subjects, including his latest novel, Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot.

Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot is available now.

For other articles included in this collection, go here.