Wales Arts Review‘s writers pick their cultural heroes in tribute to International Women’s Day – #IWD2016. (Banner image by Dean Lewis)

Peter Gaskell on Elizabeth Gaskell

I have come late to an appreciation of Elizabeth Gaskell despite the pride my family fostered in me for our association with her. The daughter of a Unitarian minister born Stevenson in 1810, Elizabeth married William Gaskell, also a Unitarian minister and cousin of my great-great-grandfather Holbrook Gaskell.

Working with her husband in his ministry after settling in Manchester, Elizabeth was moved to write about the condition of the poor. After her only son died, she found solace in writing her first novel Mary Barton (1848) which chronicles a working-class family struggling to survive and the class conflicts and hatred they face. While praised for the quality of her writing, many critics were harsh in their reviews because of her open sympathy for the working class.

The Gaskell family were close-knit by virtue of their social exclusion as Unitarians. Holbrook was himself a significant Victorian industrialist and philanthropist and we retain a signed first edition of Cranford in the family dedicated to Holbrook by Elizabeth. I first read this book in my twenties and confess to being put off by its apparent parochialism and superficiality, however charmingly Cranford was written. Since starting to take seriously my own yearnings to write, I have gone back to the book and now realise what I missed; it was the irony. In describing in minute detail the delicately planned and carefully executed set of rules by which the inhabitants live (e.g. it’s ‘not done’ to speak of one’s poverty, and is impolite to visit someone for more than fifteen minutes), she is writing in Cranford about the mundane and the slightly ridiculous to show them to be something of a bad method for tackling the social problems of her time.

It is in how she strays from the traditional superficiality of the style, that much of the interest in her novels lies. She presents them in a socially acceptable way to the audience of her day, but deliberately manipulates genre so that North and South (1854), for example, is by no means a simple romance. Much in the same way her protagonist Margaret Hale is able to combine her role as a woman with that of being the unifying force between the areas of conflict both in her society and her personal relations, Elizabeth Gaskell’s unique contribution to Victorian literature was to draw attention in her novels to the social unrest and injustices of the day, whilst also managing to indulge in the ‘ladies’ business’ of charming writing.

Nothing illustrates this better than the fact that throughout her novels, she describes costume in detail, not because of a fascination with the aesthetics of dress but as a way but to illustrate differences of class status and social expectation. A dismissal of Elizabeth Gaskell’s work in this regard as no more than charming and pretty is typical of the kind of criticism that would devalue a writer simply by referring to her femininity. Her ability and willingness to do this is a credit to her writing skills, and I would encourage anyone not familiar with her work to discover how she combines such a technique with her better known reputation for exposing the social effects of 19th century capitalism.

Paul Chambers on Carmen Cortés

My choice for this feature is not a woman whose work I have grown up enjoying since childhood, nor is it a woman who has inspired any momentous life choices. It is, in fact, a woman I have seen just once in my life. Yet, in terms of the intensity of her impact, and of her profound and elemental genius, I feel compelled to celebrate her. She is the gypsy flamenco dancer, Carmen Cortés.

Born in Barcelona yet possessing a rich gypsy heritage, Cortés acquired knowledge in Classic Dance at the Escuela del Ballet Nacional where she graduated as Titulada Superior de Danza. She has since gone on to become an icon of the most iconic of Spanish art forms.

The spirit of flamenco is most profoundly expressed in the concept of duende. Its loose definition means ‘having soul,’ yet it embodies far, far more. The duende is a mysterious force, a struggle, a heightened sense of emotion and awareness. According to Lorca, ‘seeking the duende, there is neither map nor discipline. We only know it burns the blood like powdered glass, that it exhausts, rejects all the sweet geometry we understand, that it shatters styles.’ And so it is that Cortés scorches herself upon the senses – the flashing arrow of flamenco’s archery.

In great flamenco there are moments when the scaffold of the form falls away, when your senses are suspended in darkness, when ‘with idea, sound, gesture, the duende delights in struggling freely with the creator on the edge of the pit.’ It is here that Cortés’s artistry peaks. The dove-like graces of her hands and the angular fluidity of her torso seem to burn up. Cortes paints with her fists and her knees. There is a rawness, a brutality and grace. There is a feeling, at the height of her performance, that her dancing has become so fiercely elemental that she is at the very edge of transfiguration. It is no longer dance, no longer art; it is a possession, a religious drama.

I have only ever found one great video of Cortés in performance, but recordings cannot capture anything close to the feeling of watching her perform in the flesh – perhaps for no more straightforward a reason than the fact that duende cannot be replicated. It surges, it burns up in the moment, and it ‘loves the edge, the wound, and draws close to places where forms fuse in a yearning beyond visible expression.’

While she may not possess the claim of great social and cultural influence that many of the women in this feature posses, I have chosen to celebrate Carmen Cortés because the level of her artistry is perhaps the most profound I have experienced in any performer. To experience Cortés at her most primal and elemental is to experience duende. And there can be no greater cause for celebration than that.

Jo Mazelis on Paula Rego

It was in 1988 that I first became aware of the Portuguese artist Paula Rego through a series of articles about her in both specialist art magazines and the mainstream press. Her work seemed to come out of the blue and it was everywhere. I was so surprised and intrigued by works like ‘The Maids’, ‘The Policeman’s Daughter’ and ‘The Family’, that I cut the reproductions and stuck them on the wall. All three pictures show domestic interiors in which female figures are engaged in worryingly indeterminate acts; a maid might be dressing her mistress’s hair, while another lifts a limp child, or perhaps it’s a doll, onto a chair, another girl has thrust her arm into a black military boot in order to polish it. Painted in an almost graphic style with flat blocks of colour. These strangely sturdy figures wear expressions that suggest grim intent or perverse glee. Reminiscent of works by Balthus and de Chirico, these pictures seemed to tell mysterious stories whose meaning might be guessed at or elaborated but never exactly deciphered.

At that time I had begun to write seriously and so the appeal of these paintings was perhaps as much to do with their formal properties as art objects, but also as narratives which were full of potential combined with echoes from other art forms. Like neurons firing off electrical signals Rego’s paintings set off associations with a range of other art forms that had significantly affected me over the years, from the Brothers Grimm, to the poetry of Sylvia Plath, the photographs of Diane Arbus and the fiction of Angela Carter and Flannery O’Connor. Darkness, darkness, unholy women, fury and strength and stories, stories, stories.

Rego has gone on to explore a variety of subjects; pictures and prints inspired by nursery rhymes and Jane Eyre, abortions and the Pendle Witches. Rego’s girls and women are never frail and ethereal but earthy, earthbound creatures. In a recent interview with Kate Kellaway, Rego explained how her late husband used to encourage her by suggesting, ‘Read a book and “illustrate” it.’ She added, ‘He used that word, which was a disgusting word in the art world then.’ ‘Illustrate’ is very probably still a dirty word, because it seems to suggest that the artist is subject to the writer’s imagination rather than freefalling or flying with their own. I’m pretty sure more than one writer has created fiction or poetry that emerges from one of Rego’s paintings which suggests a pleasing circularity – story to picture to story. It was certainly something I had considered as I have written stories that sprang from both paintings and photographs and yet somehow I never have.

Yet.

Elin Williams on Charlotte Brontë

‘I am no bird; and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will.’

I first read Jane Eyre when I was in year 8. Retrospectively, there was no way I could have fully appreciated it back then. I must have ambled through it several times after that, but it’s only since I began teaching it that I can wholly appreciate the inspirational protagonist who is almost undoubtedly based on the author herself.

There are many similarities between Charlotte Brontë and Jane. Although Charlotte was not an orphan, Jane’s Lowood is definitely based on Charlotte’s own school Cowan Bridge, a school which she blamed for the rapid deterioration of her two sisters’ health. Like Jane, Charlotte also became a governess, although she may not have fallen for the Byronic master or discovered that there was a mentally ill Jamaican woman living in the attic. Charlotte’s own life was maybe less dramatic than Jane’s and she came to a slightly more tragic end than her most famous character, but through Jane, Charlotte proves herself to be one of the greatest feminist figures in history.

Ann, Charlotte and Emily Brontë all wrote under the pseudonyms of Acton, Currer and Ellis Bell, thus preserving their initials. There is no unique significance to this; plenty of women authors would have been doing the same as the Brontës at this time to ensure fairness. Whilst Emily’s wild Wuthering Heights was perhaps more climactic, it is the blend of the Romantic and Gothic which makes Jane Eyre so compelling. It is strangely relevant too; in a chapter where Jane has to convince herself that she is unworthy of Mr Rochester’s love, she draws a harsh self-portrait and compares it to one of her rival, Blanche Ingram. This is not unlike stalking someone on Facebook and comparing yourself or a friend to a girlfriend of an ex or prospective lover. The only difference is, Jane never had a friend to tell her that she was better than Blanche, or that Blanche has a weird nose or funny shaped head.

But Jane’s character is not as simple as it first appears. You’d expect her to be over the moon at Rochester’s proposal, which she is, but she then begins rejecting the idea of the married mother and wife. She begins to have strange dreams in which she fails to comfort a wailing child. One critic has suggested that Bertha Mason is Jane Eyre’s double, that Bertha represents the woman who, after marriage, has descended into insanity. It is a subtle technique, but this doubling could be Bronte’s way of suggesting that perhaps marriage isn’t the be all and end all. I don’t have to tell you that for the time, this opinion expressed freely through literature would have most certainly been frowned upon, but Charlotte does it in a way which stays below the radar. I love the idea of a pompous Georgian publisher skimming over this detail oblivious, whilst Charlotte and her sisters sit in their library at Haworth chuckling. Jane Eyre isn’t likely to conform. It is only until after she has acquired her own fortune and Mr Rochester has been blinded trying to save Bertha in the fire at Thornfield that Jane can finally settle down. Sorry Mr Rochester, you lose.

Charlotte’s subtle hints towards the independent female are not only inspirational but also timeless. Feminists may argue that Jane never manages to completely free herself from a marriage obsessed culture, but to that I say that for many young women, to be considered an equal was the ideal, marriage was simply secondary. Although Charlotte herself ended up marrying, she died due to complications from pregnancy. What always makes me sad, is that because Jane Eyre was probably a sort of autobiography for Charlotte, she wrote her own desired ending. But she never got it. She never married her equal. She did, however, leave behind one of the greatest feminist tales of all time.

‘It is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal — as we are!’

Hayley Long on Tanya Donelly

To anyone who sat in their bedroom in the early nineties listening to mixtapes filled with indie rock from the 4AD record label, the name of Tanya Donelly is bound to be familiar. For everyone else, it probably won’t be. But think of a smiling, snarling, slightly weird American girl with bobbed hair, fierce red lipstick, big DMs and a properly loud guitar and you’ll be some way closer to knowing why, when I was eighteen years old, I thought Tanya was one of the coolest women in the world. And unlike her more intimidating Throwing Muses bandmate and step-twin, Kristin Hersh, Tanya seemed like a more relatable sort of girl rebel. She was sweet when she wanted to be and full of attitude if she felt like it. She sometimes sang prettily but frequently preferred to wail instead. She played the guitar how I wished I could play it – if I could even play it at all – and that was very loud and very fast. Or else in a slow repetitive drone. But, best of all, instead of singing on Top of the Pops in her underwear, she was more likely to be seen dancing in DMs on The Word. And all this was perfect for me because it meant I could dance in my DMs in my little student room in Aberystwyth and play air guitar in front of my mirror and get thoroughly carried away with the idea that the pop star shrieking out of the speaker was not Tanya – but me. From Throwing Muses to the Breeders to Belly and then on to her solo stuff, I’ve followed every musical move that Tanya has made and can measure out her career and my appreciation of it in centimetres of shelf-space filled with CDs and vinyl. There’s quite a few inches of it now – including a treasured Japanese import that I once bought for next to nothing in a shop in Brussels before scurrying, head down, out of the door in case the guy behind the counter decided he’d priced it up wrong. Last year, a lot older and a bit wiser, I temporarily put down my air guitar and went to see Tanya play her guitar for real. The venue was the Norwich Waterfront and she had reunited with Kristin Hersh to reform the original Throwing Muses line-up. Heading the band, Hersh – with her straight-ahead staring eyes, growly voice and weird head-wobble – was as uniquely odd as ever. And Tanya? She was just the same person I loved when I was eighteen; smiling and snarling and slightly weird. But middle-aged now, of course. And living proof that growing old does not mean we have to grow up and stop wailing.

Craig Austin on Louise Fitzhugh

I will never get to meet Louise Fitzhugh. Her death occurred before I had even started primary school, yet this did not prevent her from being the best teacher I ever had. An American writer and illustrator, she opened my callow eyes via the timeless character of Harriet the Spy to a mesmeric world of New York exotica; a captivating melange of dumbwaiters, egg cream sodas, and high-top sneakers. For me, a freckle-faced kid who at the time had travelled no further afield than Bristol Zoo, her writing was truly inspirational.

Fitzhugh imbued her characters with the moral and social frailties of the adult world, a stark strain of realism within children’s fiction which may now be commonplace, but which upon the book’s publication (1961) was truly radical. It was a provocation that was not initially well received, at least not from the self-appointed arbiters of morality and taste; those who felt that Fitzhugh’s writing exposed children to ‘disagreeable people and situations’. Within the pages of Harriet, the author inadvertently anticipated the American outsider oeuvre of Carrie, Rumblefish and Heathers and somehow succeeded in presenting it to a pre-teen audience in a manner that did not shy away from its underlying and unapologetically adult themes of loss, humiliation and revenge. The gut-wrenching by-products of close-knit friendships turned sour.

I yearned to inhabit the streets and blocks of the world that she created, to sit at the counter of Harriet’s neighbourhood diner, to hang out with Sport and Janie, and to inhale the glamorous drawl of a New York conversation. Harriet M. Welsch was a girl who dressed like a boy – for some commentators, a deliberate and knowing reflection of the author’s sexuality – and aspired not just to be a writer (something I quite fancied being) but to be a spy (something I actively dreamt of). For a small group of 7 year-old boys she was a revelation; the Peppermint Patti Smith of the playground, the girl it was OK to admit to liking.

I have a reissued hardback copy of Fitzhugh’s book on my shelf these days (its 50th anniversary imprint, no less), but it is the battered and dog-eared paperback of my primary school library that I always hark back to. To the faded image of the bespectacled girl in washed-out jeans and beaten-up sneakers, a metallic flashlight hanging low from the loop of her belt. The girl whose nanny, the exotic Ole Golly, once bestowed upon her the most valuable of life lessons: ‘Sometimes you have to lie. But to yourself you must always tell the truth.’

Carly Holmes on Georgette Heyer

For the number of hours spent reading and re-reading her books, and for the sheer joy they continue to give me, I offer Georgette Heyer and her Regency romances as my IWD nomination.

I first discovered these delightful, ridiculous romps when I was an early teen, and I’ve re-read them continuously and tenderly through the succeeding years. The original copies, bought with my pocket money for pennies, are now spineless and brittle but I can’t bear to give or throw them away. I’m sure I could buy updated, glossy editions (with dreadful modern covers) now without too much effort, and maybe one day I will, but they wouldn’t have my teenage yearnings (and cigarette ash) trapped between the pages, and you can bet they wouldn’t have text like: A light-hearted frolic of the most enjoyable kind…. the kind of gay story that most people would be glad to read these days written on the back.

The dialogue is racy, you are informed (or warned), and the situations nothing if not provocative. Well, if you’re shocked by dialogue that’s all Zounds! and Bodkins! and By Jupiter! then it’s racy indeed, and the situations are as provocative as a slightly skewed fairy tale. There’s a boy, and there’s a girl. There’s a lot of misunderstanding strewn along the road to happy ever after, maybe a duel or two, and an inordinate amount of Zounds! before the boy gets the girl, or the girl gets the boy, and all is well. But you know (the way you always know in the best stories) that it’s going to be okay in the end. There’s no need to be anxious that one of them will die, or the world will implode, or something post-modern will happen to screw it up. She’ll be feisty and he’ll be imperious and you’ll learn quite a bit about post-chaises and the type of wig worn in the Regency period, and then, on the last page, he’ll kiss her ruthlessly and I’ll suppress an overwhelmed sob and teeter upstairs for a much-needed nap.

I don’t think I’m selling the whole Georgette Heyer experience as well as I could be. Yes, her books are pure pleasure in the reading sense, and they aren’t particularly challenging, but they’re not mere fluff either. She clearly had a great sense of humour and appreciation for the ridiculous. The prose bowls along and the characters are always lovable and believable, no matter what unbelievable scrapes they get into. Like a sun lounger and a glass of wine on a warm evening, or a dressing gown and a cat on your lap on a cold night, a Heyer Regency romance is my ultimate comfort read.

Bethany W. Pope on Artemisia Gentileschi

Artemisia Gentileschi was an Italian baroque painter who is now considered second only to Caravaggio in terms of talent and composition. When I was a child I was lucky enough to see one of her paintings hanging in the Ringling Museum in Tampa, Florida, and it has stuck with me ever since. Born in Rome in 1593, the eldest child of the painter Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia showed her talent from an early age; she was the child that her father chose to train.

Her forms are naturalistic; steering away from idealism and focusing on the gritty flaws, the blood and textures, that allow paintings to breathe. At that time, in Italy as well as across Western Europe, women were discouraged from participating in public life any way. Artemisia (whose name derives from Artemis, goddess of hunting) did not allow those cultural biases to slow her down. She composed her first major work (‘Susannah and the Elders’) at the age of seventeen. The subjects that she chose to work with were referred to, then, as belonging to the genre ‘the power of women’ and all of her work has a profoundly feminist theme; dealing with the many injustices committed against women at that time — and often containing a response to them. This response was not always hypothetical. During one of her later periods of study, Artemisia was raped by her teacher, Agostino Tassi. At that time it was very unusual for a woman to take her rapist to court (the process was long, difficult, and the burden of proof, like now, was entirely on the victim) but Artemisia did it — and won. This victory was double-edged; on the one hand, she attained some measure of justice. On the other the trial gave audiences an excuse to focus on her personal history (her life, as an object) rather than her work. However, the experience (of the dehumanizing trial, as much as the rape) led Artemisia to paint her great masterpiece Judith Slays Holofernes. I was lucky enough to see the painting in the flesh earlier this week. It is a work of terrible control and perfect rage. Translucent blood spatters the golden breasts of Artemisia’s Judith as she works. Beheading a man is no easy task and her face is full of concentration at the effort. She is a woman bent on liberating her people, and she is calmly dedicated to the task.

Her forms are naturalistic; steering away from idealism and focusing on the gritty flaws, the blood and textures, that allow paintings to breathe. At that time, in Italy as well as across Western Europe, women were discouraged from participating in public life any way. Artemisia (whose name derives from Artemis, goddess of hunting) did not allow those cultural biases to slow her down. She composed her first major work (‘Susannah and the Elders’) at the age of seventeen. The subjects that she chose to work with were referred to, then, as belonging to the genre ‘the power of women’ and all of her work has a profoundly feminist theme; dealing with the many injustices committed against women at that time — and often containing a response to them. This response was not always hypothetical. During one of her later periods of study, Artemisia was raped by her teacher, Agostino Tassi. At that time it was very unusual for a woman to take her rapist to court (the process was long, difficult, and the burden of proof, like now, was entirely on the victim) but Artemisia did it — and won. This victory was double-edged; on the one hand, she attained some measure of justice. On the other the trial gave audiences an excuse to focus on her personal history (her life, as an object) rather than her work. However, the experience (of the dehumanizing trial, as much as the rape) led Artemisia to paint her great masterpiece Judith Slays Holofernes. I was lucky enough to see the painting in the flesh earlier this week. It is a work of terrible control and perfect rage. Translucent blood spatters the golden breasts of Artemisia’s Judith as she works. Beheading a man is no easy task and her face is full of concentration at the effort. She is a woman bent on liberating her people, and she is calmly dedicated to the task.

Cath Barton on Errollyn Wallen

I first encountered Errollyn Wallen’s music when I sang in the community choir for her work about coal and its importance in the lives of the people of the South Wales valleys, Carbon 12. I remember some of my friends who didn’t read music struggling early on, our conversations as we travelled to and from rehearsals in Merthyr when I encouraged them to stick with it, and finally our pride as a choir when we sang in the première of the work in the Millenium Centre in Cardiff. Not one of those doubters had dropped out. Afterwards, in the bar, Errollyn was there thanking us, but really we all wanted to thank her. It was such a thrilling piece in which to perform, and incredibly emotional – I can feel even now what it was like singing about Aberfan.

That was in 2008. Five years later I was writing a piece about youth opera for Wales Arts Review, and while researching one of the people I spoke to was Errollyn. I was touched that she was so pleased to hear I’d been part of Carbon 12. When we talked on the phone she mentioned a new piece she was writing called ANON. It was a commission (as Carbon 12 had been) from Welsh National Opera, and was to be part of their 2014 Fallen Women season, taking a fresh look at the story of Manon Lescaut from the perspective of the silenced woman. I was intrigued to know more and a few months later I was in a rehearsal room listening to the work in progress. I’d gone as an observer of the process, but Errollyn would not hear of me sitting out when everyone gathered at the end of the day, inviting me into the circle to join the discussion.

As rehearsals progressed for this chamber opera about exploitation of women around the world, I was privileged to be treated by Errollyn as one of her team. She always welcomed me, and shared thoughts as rehearsals progressed. I went on to write two pieces for Wales Arts Review about ANON, and subsequently, encouraged by Errollyn, to give a paper about it at the 2014 Music on Stage conference at Rose Bruford College.

I have huge respect for Errollyn Wallen as a musician and as a person. She has encouraged and inspired me and continues to do so. Looking back at an interview she did with Laura Barrett for The Guardian in 2008, I see that when asked what soundtrack would feature on the soundtrack to her life Errollyn said it would be ‘Dido’s Lament’, as ‘there’s something transcendent about it’. I’ve just pre-ordered a copy of Errollyn Wallen’s new CD, PHOTOGRAPHY, and at the end of the promotional video she’s singing that very piece. Not operatically, but with heart, like everything she does.

Nigel Jarrett on Jeanne Moreau

The French actor Jeanne Moreau made a huge impact on me when she appeared in Truffaut’s film Jules et Jim. If the pantheon of distaff celebrity might not permit her entry, she deserves to head the queue at the side door. I first saw Jules et Jim when so-called ‘Continental’ films were intensifying and extending my insane devotion to cinema. By ‘Continental’ was meant ‘foreign’ and by ‘foreign’ was usually meant ‘French’, at least from where I was sitting in the old Globe cinema at the junction of Albany Road and Wellfield Road, in Cardiff. The funny thing is that only now, decades later, do I refer to her as an actor when at the time, with her character in that film oddly blurring distinctions of gender, at least at the start, the term ‘actress’ should have sounded weird. But these things take time. I mean enlightenment. Recognition that there are events called gender wars and that such recognition should result in an immediate cessation of hostilities takes an inordinately long time to become part of the way society, or the best section of it, thinks.

There’s a scene in the film where the ever-playful trio, creating a kind of halcyon period in advance of the Great War, has the Moreau character (Catherine) dressing up as a man, complete with moustache. Although there were different things going on in the relationships among the three, it was clear that it would resist descending to a retrograde and bourgeois ménage a trois and that Moreau was not so much a foil but an equal. One of the criticisms of the film was that nothing happened in it, at least nothing of the irrationally tormented sort one associated with a woman detaching herself from one man and attaching herself to another to the first man’s unhappy detriment. Actually, humanity being what it is, alliances are made: Jim and a woman called Gilberte are already an item and Jules and Catherine love one another to the point of wanting to marry. The three are happy with that. After the war, the men, who fought on different sides, meet again when Jim visits Jules and Catherine to discover that Jules is tormented by his wife’s love affairs, which eventually include his friend.

All does end unhappily but it is Moreau as the free-spirited woman whose depiction stays in the memory, not because any man could yet cope with her behaviour but because she cannot help herself and is the pivot on which a new kind of domestic arrangement might have prospered. Most of us still couldn’t manage it. Catherine (in the film and in the book by Henri-Pierre Roché on which it was based) is an equal in friendship and in marriage; despite the violent end, the mood is an idealistic ‘one for all and all for one’; what kills it are not so much social expectations – there are few, if any, hinted at in the film – but the claims of gender and sexuality.

So is this appreciation about a fictional woman or a real film actor? The thing is, I’ve always thought Moreau might have been playing herself, mutatis mutandis, in Jules et Jim. Everything I’ve read about her confirms the impression. She told The Guardian newspaper that her ‘inner freedom’ obviated the need for her to join a group and ‘toe the party line’. Of her latest relationship, at 74, she said, ‘I need absolutely to be alone. You can be a couple without being in each other’s pockets. I don’t see why you should have to share the same bathroom, even when you have two bathrooms. Don’t take care of yourself because you want to stop time. Do it for self-respect. It’s an incredible gift, the energy of life. One’s aim should be to die in good health, just like a candle that burns out.’

Easier said than done for the majority of us, but said with conviction none the less. Forty years after she’d played Catherine in Jules et Jim, she might still have been adding to the script. And the words could equally have been spoken by a man. If only the two could come close enough, sans frisson, to agree. We could sign a peace treaty tomorrow.

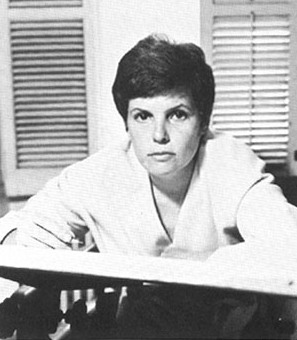

Emily Garside on Gillian Anderson

Gillian Anderson always seems to come into my cultural life at the right times. First when I was an awkward and nerdy teenager, she appeared as Dana Scully. Later, as a still awkward, still nerdy twenty something, Anderson reappeared as Stella Gibson, one of the best television detectives of modern times. Again showing me that smart was good, and that women didn’t fall off the face of the earth at 30.

Scully was the first really intelligent woman I remember seeing on TV who wasn’t there just to be mocked for it. And, later by association I found Anderson to be similarly uncompromising and unapologetic about who she was as a person, and as a woman. Scully and by default, Anderson was also criticised for the way she looked – if I recall the line was ‘her legs weren’t long enough, her boobs weren’t big enough and her hair not blonde enough’ and still Anderson was still voted top of numerous ‘sexiest women alive polls’. And while it may seem contradictory to praise such things as a feminist statement, actually for many women, including myself, it was an inspiring thing. That it was possible to look different, be different and be yourself: it’s not un-feminist to want to be considered attractive. Gillian Anderson’s antidote to the beauty standards of the mid-90s were refreshing and important for young women. Coupled with a television character who was smart and strong.

In part it’s the roles she’s taken over the years that make Gillian Anderson such an iconic cultural figure for me. From these fierce detectives, Scully and Gibson, to her stage roles, less well-known, but still daring, strong women. On stage Anderson has taken on an adulteress without repentance, a woman facing her mental illness, and the always iconic and complicated Blance du Bois in A Streetcar Named Desire. Consistently playing the strong, complicated women, when there were no doubt more offers and more money for lesser women, Anderson has never let me down.

Anderson has always been a voice for women as well. From refusing to accept less money than her male co-stars, to hitting out against accusations of plastic surgery with a series of pictures captioned ‘this is what I really look like’. Gillian Anderson continues to be a woman whose voice in culture through the roles she plays, and in her own right, is still an inspiration to me some 20 years later.

Jane Roberts on Anais Nin

I first encountered ‘nin’ as a third person pronoun in Homeric Greek; it was a dull bullet of embellishment on the page, although a necessary compass point of understanding in the sentence. I came late to Anais Nin, reading for pleasure rather than as a scholastic endeavour; as familiar as the pronoun ‘nin’ had become, I soon realised there was nothing prosaic about Anais Nin – the writer, or her writing.

Most of the erotica was written on hungry stomachs.

A famed memoirist and essayist, many of Nin’s short stories and erotica were published posthumously. Whether her erotic short stories were written merely for amusement, or, battling a continued state of impoverishment, to earn money for food, or as a creative exercise – that these stories live on beyond the life of their author speaks of a readership wishing to claim ownership of a secret, almost forbidden, world. Nin spoke of the erotic writing as a form of ‘prostitution’. Money matters aside, there is a sense of freedom in using her talent to produce work that was never intended to be orthodox, work that was never intended to be widely published. A prostitute for money or enslaved to Muse, the erotica is a showcase of a writer letting loose with confidence and skill.

We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.

The world of Nin is rich with a developed sense of diversity that reflects her own life in Paris, Spain, Cuba, and then New York; assured elements of internationalism perhaps more associated with the male writers of her time. Not confined to geography, in depictions of escapism and reality, Nin gives the reader a mirror in which to reassess aspects of the internal and external.

I was immensely disappointed by his conventional attitude.

The shock factor of Nin’s erotica weighs heavy at times. Perhaps more due to the familiarity and rediscovery of what is – or should be – natural, rather than voyeuristic discomfort.

Her use of language is both abrupt and loquacious: simplistic description can be imbued with searing depth of meaning; the seedy side of life painted with the delicacy of an Old Master. She is mistress of sensory delight that so many writers have failed to pinpoint even today.

The most intimate exchanges in Nin’s erotica are not the more salacious scenes alone, but the dialogue and exploration of the human condition. Universal truths – witticisms, pains, hungers, delights – stretch out on the page, as stark and naked as some of her characters.

The sexual life is usually enveloped in many layers, for all of us – poets, writers, artists. It is a veiled woman, half-dreamed.

Nin can be said to be largely responsible for reclaiming erotica for women – both in writing and reading. Yet she is more – a pioneer voice from beyond the grave for all those she has inspired to lift the veil of convention.

Adam Somerset on George Eliot

Some authors, like some acquaintances, arrive without a specific association of time or place. Others have an indelible fixity of both. I came across George Eliot in the first months of 1975. The place was a glacial Berlin.

Berlin was not just epicentre of the Cold War but host of a cold I had never known before, the temperature hovering at zero for weeks on end. The statelet in the East was awash with soldiers and weaponry on show. That was to be expected. But the West was little better. The University- after Britain it looked a litter of graffiti-strewn modern buildings- was in a state of semi-lockdown. The second generation of the Rote Arme Fraktion had kidnapped Peter Lorenz, a candidate for the Berlin Mayoralty, that February. The police in the West were as thick on the ground as the VOPOS in the East.

The Deutschmark had soared and the pound slumped with Labour Party and Government back home split over the forthcoming referendum on EU membership. That meant the visiting student had no money, no friends and a university under police occupation. But I had three items of cutlery, three pieces of furniture and a dissertation to research. And Berlin had a little bit of home in the well-warmed, machine-gun-free library that belonged to the British Council. There I came across Middlemarch.

I knew nothing of the ferocious intellect that had been translator into English of David Friedrich Strauss. I knew nothing of the private life with George Henry Lewes. It was just a book, a monster, but one that heaved with vitality. As a historical novel it bristled with politics with Reform in the air. The prose delivered crisply ironic character summations. And there was a immanent wisdom. Eliot starts one chapter with the simile of a table scored with scratches. With a candle placed upon it the light turns the random scratches into marks of order and beauty.

There are great cruelties in the world. Over that winter the press front pages were regularly reporting the steady victories of the Khmer Rouge towards Phnom Penh. But there are equally a myriad of small tyrannies. Eliot gives her Reverend Casaubon an opening self-description: ‘My mind is something like the ghost of an ancient wandering about the world and trying mentally to construct it as it used to be, in spite of ruin and confusing changes.’ With the marriage to Dorothea Victorian convention forbade explicitness of today yet George Eliot says it all.

The second volume of Middlemarch was published in the year that Nietzsche wrote The Birth of Tragedy. Eliot closes her nine hundred pages on an emphatic un-Nietzschean note. It is a paragraph that reads as true now as to the twenty-two year old then. ‘The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts…half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.’

George Eliot: a hero to celebrate.