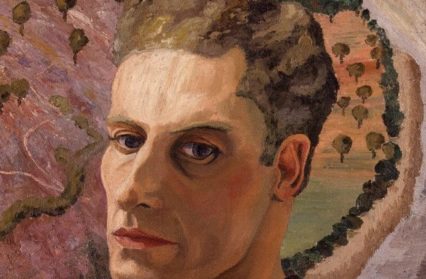

To mark February as LGBT History Month, we publish Norena Shopland’s incisive essay on the life and work of Cedric Morris, extracted from her new book, Forbidden Lives.

In 1937 a Welshman moved to pink-coloured house in Suffolk and opened an art school with his partner. The school would come to greatly influence not only artists, many of whom become famous in their own right, but also horticulturists. The Welshman was Cedric Lockwood Morris from Sketty, Swansea. A member of one of the great local industrial families – one which descended maternally from Owain Gwynedd, the twelve century prince of North Wales. Like many families of wealth it had its characters. They included a bank manager who conveniently rearranged the figures in profit and loss columns and was imprisoned for two years. And the woman-chasing ancestor whose sickly wife was confined upstairs whilst downstairs he kept a mistress. Who, when the wife died went to her funeral dressed in every piece of the dead woman’s jewellery.

Cedric, as his partner Arthur Lett-Haines later put it, “was born, of phenomenal vitality, on December 10th 1899.” His parents were Sir George Lockwood Morris and Wilhelmina Cory: George was the great-grandson of John Morris who had founded the Swansea suburb Morriston. He also played rugby for Swansea and was the first Swansea player to represent Wales. Wilhelmina also came from a local influential industrial family the Cory’s of Swansea, and there had been various marriages between the Morrises and the Cory’s. She and George had three children, Muriel who died in her teens, Cedric and Nancy. Just three months before he died George inherited the Morris baronetcy from a distant cousin.

Art played an important part in the Morris family. Cedric’s great-aunt Margaret Morris married the art collector and dealer Noel Desenfans. Using her marriage dowry she became one of the three founders of the Dulwich Picture Galley, the oldest public art gallery in England– and was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Cedric’s mother had studied painting but Cedric did not immediately take to art. As a young man he seemed unsure of what he wanted to do. After being educated at Eastbourne and Godalming he failed the entrance exams for the army. “Bored and nonconformist in his father’s household,” Lett later said of him, “he made off to Canada. There he worked as a hired man on ranches in Ontario where the farmers seem rather to have taken advantage of his unusual energy and his naif [sic] ignorance of standard wages in the New World … Eighteen months later, he seems to have been studying singing at the Royal College of Music under Signor Vigetti, whose attempts at raising his light baritone to a tenor were unsuccessful”.

Giving up on the singing, Cedric travelled to Paris to study art in April 1914, where he enrolled at the Académie Delecluse. However at the outbreak of World War I he returned home and enlisted in the Artists Rifles, a regiment of the British Army Reserves. The Rifles had been formed in 1859 and consisted of painters, musicians, actors, architects and other creative professions. As they were about to leave for France Cedric was declared medically unfit for military action and was sent instead to Berkshire to train war horses.

He was discharged from the army in 1917 and moved to Newlyn in Cornwall where he became the friend of struggling artist from New Zealand called Frances Hodgkins. In November 1918 he went to London for Armistice Day when he met and fell in love with the man who was to be his partner for the next 60 years.

He was discharged from the army in 1917 and moved to Newlyn in Cornwall where he became the friend of struggling artist from New Zealand called Frances Hodgkins. In November 1918 he went to London for Armistice Day when he met and fell in love with the man who was to be his partner for the next 60 years.

Arthur Lett, born in 1894 in London, was one of three children of the architect Charles Lett and Frances Laura Esme. After their divorce his mother married S. Sidney Haines, so Arthur changed his surname to Lett-Haines. He too enlisted and served in the Royal Field Artillery. He became a Second Lieutenant and was wounded fighting in Mesopotamia.

In 1916 Arthur, or Lett as he was commonly called, married Gertrude Aimee Lincoln, the granddaughter of Abraham Lincoln. Soon after the two men met and fell in love Cedric moved in with Lett and his second wife. The three planned to move to America but in the end Aimee went by herself.

The two men went instead to Newlyn and afterwards to Paris in 1920, becoming part of the artistic community which included Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Nancy Cunard and Ernest Hemmingway among others. Kathleen Hale, with whom Lett had a long affair, recalled, “I remember them coming gracefully towards us along the Boulevard like gazelles, both in light-coloured socks, the two of them extremely handsome and elegant.” Returned to London in 1926 they set up an enormous studio in Great Ormond Street where, quite open about their relationship, they hosted legendary bohemian parties attended by many gay and bisexual people.

By the late 1920s Cedric had become an enormous success as an artist. His second exhibition in London featured a series of nudes many of which his grandmother disapproved of and at the exhibition turned them to face the wall. Cedric was also receiving other commissions such as poster designer for Shell and BP. Indeed so well was his career advancing and so poor were his promotion and administration abilities that Lett put his own career on hold to promote that of his partner.

They both joined a number of organisations such as the newly formed London Artists Association helping young artists with promotion and financial help. They joined the Seven & Five Society (seven painters and five sculptors) another new project to promote modernist art. The Society staged the first exhibition of abstract art in Britain. Cedric and Lett became part of an elite London circle which included D. H. Lawrence, the Sitwells, Wyndham Lewis (who was often criticised for his hostile portrayals of homosexuals, Jews and other minorities) and Ben and Winifred Nicholson.

Certain members of the Seven & Five became disillusioned with the way the society was being run. When Ben Nicholson became chairman he introduced a ruling that exhibitions could only show abstract work. Cedric, who was painting flowers, animals and portraits, was effectively barred from exhibiting and was the first to leave.

Disillusioned with much of the London art world and its rules Cedric and Lett decamped to the countryside, to the pink-coloured farmhouse called Pound Farm in Higham, Suffolk. In nearby Dedham they set up a modern art school. At Pound Farm Cedric was able to pursue his other passion – the painting, growing and breeding of flowers.

Within a year they had 60 students at the school and Pound Farm had become a magnet for students, artists, visitors to the spectacular garden that Cedric had designed and for the legendary parties they held. In 1932 Vivien Gribble, the wealthy owner of the farm and a wood engraver and student of Cedric’s, died and left the property to him. Seven years later young student Lucian Freud, grandson of the psychoanalyst, may have burnt the place down by leaving out a cigarette. Alfred Munnings the artist and president of the Royal Academy of Arts lived locally and he had a passionate hatred of modernism. He had his chauffer drive around the smouldering ruins as he cheered loudly the destruction of what he saw as an odious development in art. Unperturbed, Cedric suggested the students paint the ruins.

The school re-opened in Benton End, where it became a hot house of modern talent for the next forty years. Cedric and Lett did not teach using traditional methods. Instead they believed in a free rein approach which they had experienced in the French schools. Instruction was kept to a minimum with, as one student putting it, more a ‘sitting at the feet of the master’ approach. They believed artists should paint influenced by their feelings rather than rely on academic learning. And part of the success of Benton End was the contrast between its founders and between the different kinds of art in which they specialised. Lett was a painter and sculptor who experimented in different media but generally was a surrealist. Cedric painted portraits, landscapes and still lives of flowers and birds aflame with colour, in a more a post-Impressionist style. He was passionate about colour and many of the artists who stayed at Benton End show the same vitality in their work. Lett once said that apart from Matisse Cedric was the finest colourist of that century. His teaching for both painting and horticulture was that the only rule is that there are no rules.

Shortly afterwards the writer Ronald Blyth was introduced to Cedric. “I was initiated into a realm of flowers, botanical and art students, earthy-fingered grandees and a great many giggly asides which I didn’t quite get … The doors and window-frames of the ancient house glared Newlyn blue and there was a whiff of garlic and wine in the air from distant kitchens. The atmosphere was well out of this world so far as I had previously witnessed and tasted it. It was robust and coarse, and exquisite and tentative all at once. Rough and ready and fine mannered. Also faintly dangerous.”

It was dangerous because it was a place where anyone’s sexuality was accepted at a time when homosexuality was still against the law. But most at Benton End knew about their relationship and regarded them as an old married couple. They had a stormy but successful relationship despite both having affairs with other people. Cedric with the painter John Aldridge and the American artist Paul Odo Cross, the latter causing tension between Cedric and Lett. Lett was more bisexual than homosexual he mainly had affairs with women such as Stella Hamilton but probably his most long-term affair was with Kathleen Hale. Known mainly for her children’s books Orlando the Marmalade Cat she drew inspiration for many of the stories and the illustrations from life at Benton End. She was for a while secretary and lover of Augustus John, of whom she made a portrait. Describing their affair in her autobiography she wrote of how important Augustus and Dorelia were to her. “I was smitten,” she told the Independent, “I’m not a lesbian but I really was in love with Dorelia, I think. She was very funny, so beautiful and naive.”

Geordie Greig, in his biography of Lucian Freud, Cedric’s great admirer, said, “It was a refreshingly uninhibited time for the students at Cedric Morris’ … ‘everyone was homosexual or lesbian at the school, or so it seemed.’” Among them was Frances Mary Hodgkins, now regarded as one of New Zealand’s most prestigious and influential painters. She had a series of affairs with women, and was a close friend of Cedric and Lett. They also included Denis Wirth-Miller and his long-term partner Richard Chopping who did some of the most famous dust jackets for the James Bond novels. Richard, influenced by Cedric, became a botanical and zoological painter. Richard and Denis were the first couple to register a civil partnership in Colchester.

Cedric spent as much time with his garden as he did with his students. He is probably best known for his award winning iris collections, which included the first pink specimen bred in Britain. So attached was he to his garden Lett was more jealous of it than any of Cedric’s lovers.

Students were often expected to do the gardening and housework as well as painting. Lett was called ‘Father’ by all the students and it was he who took care of the community, of the administration and for cooking two meals a day for all the students. Invariably with a drink in hand he produced large, delicious meals even during war-time rationing, by plundering the garden and hedgerows to make soups and casseroles laced with ash from his cigarettes. Having given up his own career to support Cedric he came to hate his partner’s passion for horticulture, and cooking became his creative outlet. Bernard Brown, a local boy and student who went on to become a lawyer recalled, “Lett Haines was the first man I had seen in an apron and the only one before I left Suffolk.”

The house was never that clean or tidy and was filled with pictures, the smell of flowers, numerous people discussing art and plants, marmalade cats, formidable women, wine and exotic birds. Lett’s kitchen, his personal domain, was chaotic but he created delicious food and drink. He rarely ate with them preferring to take a sandwich to his bedroom which doubled as his studio. However he was also the story-teller of the house, telling scandalous tales about himself or of his and Cedric’s travels and encounters, occasionally corrected by Cedric. His stories were designed to shock and many of the naïve young students did not always follow his innuendos. “Lett talked through a big wicked smile like the wolf-grandmother in Little Red Riding Hood. With his large grand and rearing, scarred bald dome, a legacy from the Western Front, and his mocking courtesy, he made no bones about dominating the scene.”

Bernard Brown recalled “Words cut out from newspapers and cinema posters, then put together in sentences, decorated the walls. Their messages eluded me, but doubtless they were very funny and in keeping with the generally fey atmosphere of the place. There were big heavy-framed paintings upon most walls and many more stacked along the main hallway and in the studio. There was a huge nude of a lady from Raydon. I had often seen her biking to Hadleigh and it was years before I could pluck up the courage to enter the shop where she served.”

Cedric, on the other hand, was extremely disciplined and worked hard on both his paintings and gardening and had nothing to do with the house. He was an elegant figure in his corduroy trousers, Welsh linen shirt and soft silk scarf, but with dirt and paint covered fingers. He could hardly boil an egg and rarely wrote a letter. When he sold a painting Lett would have to check if he actually took the money. It was stuffed forgotten into a pocket. Lett rarely went outside and on a doctor advising him to get more fresh air he went into the garden once.

Cedric and Lett were like an old married couple but sometimes there were occasions when their relationship was strained. Then Lett would avoid sitting at the table if Cedric was there and they would have stormy rows as the students sat quietly by. Or other times when one or the other would stomp off and not speak to each other for weeks. But it worked – for 60 years it worked.

The power of their personalities and their dedication to art won over many people. Both had a wicked sense of humour, although Cedric did not suffer fools gladly. He disliked the hordes of women who arrived to view his garden and often walked off, having lost patience with them. One woman he particularly disliked so much that he presented her with a plant called Dracunculus vulgaris. Not telling her as she got in her car to drive home on a hot day that it is one of the worst smelling flowers in the world.

Cedric was also an avid animal lover and the house was a menagerie. Cats ran all over the place and were fed by Cedric at midnight. He had a long running feud with a local gamekeeper who would shoot at his and other people’s cats and dogs – a feud only ending when the man tripped over his own shotgun and killed himself.

Despite spending most of his life in England Cedric considered himself Welsh and he proved an important influence on Welsh art. He returned often to south Wales, and the suffering of the people in the valleys during the Depression influenced him greatly. He painted Caeharris Post Office and Dowlais from the Cinder Tips, Caeharris during his time there. In the years after the First World War Welsh art was not widely appreciated. Little was exhibited in London, with the exception of artists like Sir Goscombe John, David Jones and Augustus John, and there was an equal lack of appreciation at home. Cedric organized an Exhibition of Contemporary Welsh Art in 1935 in Cardiff which led to the founding of the Contemporary Art Society for Wales. In a radio interview about the exhibition he called for a community in art to be developed, a Welsh magazine and the organisation for exhibitions. That same year the South Wales Group was founded on very similar lines to the exhibition and Cedric became a member. He was also closely involved with the Merthyr Tydfil Educational Settlement at Gwaunfarren House which had been set up in 1937 providing education and welfare services to people suffering in the Depression. The Educational Settlement was also a focus for Esther Grainger, Heinz Koppel, Glyn Morgan and Arthur Giardelli[1].

Cedric taught at an art centre set up by the philanthropist Mary Horsfall in Dowlais. He knew Heinz Koppel a German Jewish émigré who had fled Germany in 1933. Ten years later, through Cedric’s influence, Heinz was teaching art at the Merthyr Tydfil Education Settlement. This later grew into the Merthyr Tydfil Arts Centre with Koppel as principal.

Cedric also encouraged Welsh artists to become students at Benton End. Glyn Morgan from Pontpridd was taught by Ceri Richards at the Cardiff College of Art and was introduced by him to the works of Picasso and Augustus John. Whilst on a visit to Cardiff Museum he first saw a painting by Cedric Morris which was to influence him for the rest of his life. Cedric judged a show at Pontypridd in which the 17 year-old Glyn had entered two pictures. Cedric thought his work had promise and invited him to join the school at Benton End, which he did in 1944 and said it was “just a lovely place to be.” For the next 38 years he would return as often as he could, and his art reflects the vibrancy and colours that is present in Cedric’s work.

The Second World War saw the numbers of students fade away and the bohemian reputation of Benton End gave rise to rumours what went on at the house. There was talk of sheltering spies and storing ammunition, which weren’t helped by Cedric and Lett’s lax attitudes towards black-outs. Locals believed they were signalling to enemy planes. Things reached a head when a damaged plane jettisoned its bombs on the old Mill House a mile from Benton End. Ah, said a local, one of them arty types had painted the Mill just a fortnight ago. And before long a rumour was running rife that the artists had been painting local scenes to send to Germany.

By the 1960s the school had more or less ceased to function. Lett had more time for his own work and produced a number of small sculptures made from animal bone left-overs from his cooking, which he called his ‘Humbles.’ By the mid-1970s Cedric’s eyesight was failing and he had almost given up painting. He desperately wanted to visit Wales again and a friend, John Morley planned a visit to the Gower, but it never came about. The school officially closed when Lett died in 1978 but Cedric continued to live there. As he grew old he cursed God, “whom he still took to be some ghastly Sunday misery from Glamorgan, for ‘insulting’ him with old age.”

Cedric died in 1984. His obituary in the Times stated that ‘he was unmarried’. Like so many forbidden lives the people they loved were simply airbrushed out. Cedric and Lett were like thousands of people who lived married lives, but didn’t have the word or the certificate to prove it.

Forbidden Lives: LGBT Stories of Wales by Norena Shopland is available now from Seren.