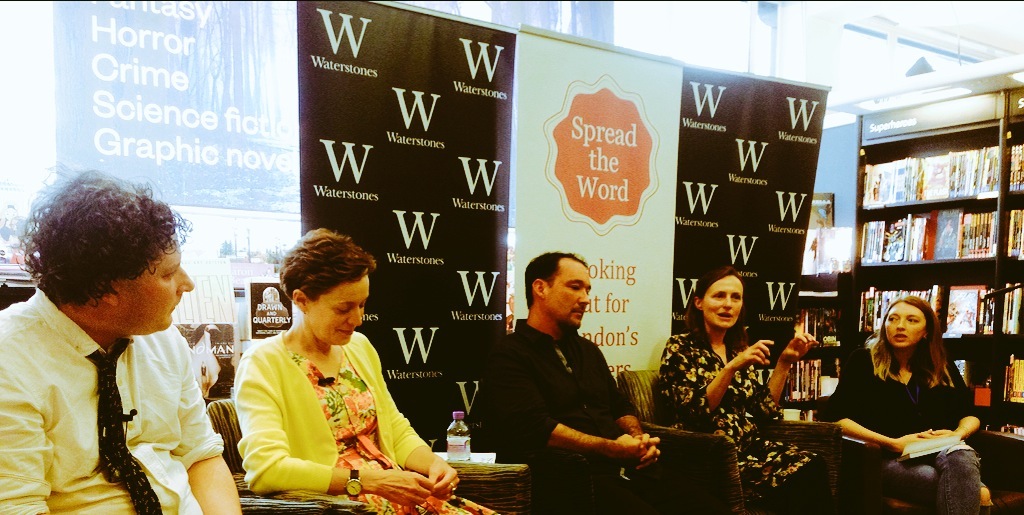

The second annual London Short Story Festival (LSSF) was hosted in the beautiful and inspiring setting of Waterstone’s Piccadilly, the largest bookshop in Europe. The event was again presented by Spread the Word and curated by the author, Paul McVeigh; together they not only enabled but also embodied the spirit of the festival. It was an open, friendly, very well organised four days spent with readers and writers alike in the heart of London. It had none of the reserve or cynicism often levied at literary events and I think this is testimony to the founding ethos and good spirit behind its inception.

Spread the Word is a company dedicated to providing high quality, accessible opportunities for writers to develop their talent and careers. Their commitment to inclusivity and promoting diversity is evident in the wide range of voices shared throughout the festival. As McVeigh puts it; the festival was ‘a unique opportunity to expand the kind of short stories we’re used to hearing’. Not only did they run the ‘Free Ticket Scheme’ to make the event accessible to all but additionally the ‘Writers’ Space’ offered a programme of free activities.

In an interview for Wales Arts Review earlier this month, McVeigh explained how he wanted to take the opportunity to develop partnerships with important UK literary organisations, while at the same time making the festival an outward looking, international event. Boasting an impressive line-up of sixty-five writers from all round the world, as well as (among others) links with Word Factory, Booktrust, BBC National Short Story Award and the Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award, I think we can safely say that Paul achieved this goal. A mix of household names and emerging talent delivered a genuine celebration and exploration of the short story form.

‘An Evening with Ben Okri’ was the headline event on the opening Thursday and also featured a reading from Irenosen Okojie, a promising new author chosen by Okri himself to read an extract from her ambitious debut novel, The Butterfly Fish. Okri opened the discussion by musing on how people tend to read too quickly and too lightly, claiming that it takes time to grasp the ‘music’ of the text. He admitted to having once prided himself on being an extremely quick reader but that he had discovered in recent years that he misses less and gains more from a text by being a slow and patient reader. This tied in with the notion of writing as a ‘seeing of thoughts’. Namely, that the writer starts with a mood and finds a way to what they are thinking through the act of writing. In this way, writing and reading are a way of seeing thoughts and taking them where no other thoughts can go. This thought-place is the legendary world, the one inhabited by each of us and shared by few. This was reflected in the magical elements of the worlds revealed within the pieces read, particularly in a full length reading of Okri’s favourite of his own short stories, ‘Incidents at the Shrine’. The art of the short story was then described as a ‘bringing into the light’. The idea that the story links to and indicates what is beyond it as well as what is within it. The reader has to work and use their imagination to follow the thoughts and fill the gaps. This is what makes the story dynamic, exciting and challenging.

‘What are you laughing at?’ opened with an uproarious reading of Salena Godden‘s unashamedly filthy, ‘The Good Cock’, with occasional pauses to allow parents to hurry their children from earshot. It was a perfect example of how people can unite through humour and acted as an undoubted shot in the arm on the slightly snoozy late afternoon audience. The style and use of comedy in all the readings was remarkably different and as such represented the diversity of purpose humour can support. In the following panel discussion there was much musing on whether a successful book had ever been written which was totally devoid of humour. 1984 was the only such work that anyone could think of.

Comedy was described as a ‘hook’ for the reader that then enables the author to deliver a heightened emotional punch. It can be seemingly straightforward whilst at once being evasive, expressing a central frustration or confusion. Structure and form were fundamental, both in framing the story and in delivering the jokes to the reader in a nuanced and deliberate way. In this way the form of the joke; repetition, set-up and punch line; were all a key part of the stories’ successes. Again the diversity of this form was demonstrated in the differences between the stories themselves. Selena Godden’s story was seemingly straightforward and carefree, but revealed an emotional darkness and loneliness. The second story by Nikesh Shukla was a rhetorical musing on the frustrations of writers block, full of both isolation and frustration. The third story by Stuart Evers drew on the juxtaposition between the private and shared world of comedy, how simply not getting the joke can embody isolation. In every sense comedy was storytelling; demonstrating the importance of the ‘set-up’, introducing ideas at the right time, ending the story at the right time and as Okri extolled, leaving space for the reader to determine what is revealed.

Friday was concluded with a celebration, 10 Years of the National BBC Short Story Award. The panel were made up of 2011 winner DW Wilson, 2011 judge Joe Dunthorne, 2012 finalist Krys Lee and also Liz Allard, the BBC short story producer responsible for translating the winning entry from page to radio. Following a series of brilliant readings, which included a mesmeric, typically bittersweet new short story from Dunthorne, the discussion centred on the question of ‘what qualities do the best stories have?’ This was a unanimous and succinct discussion. Great stories should provide the unexpected and surprise both writer and reader. They should haunt the reader; they should be almost remembered like deja-vu. The panel agreed that there is a sense of uncanny relief in finding the best; you simply know when you read it. Finally, great stories should have a sense of grandiosity, a scope bigger then the page. Again, this comes back to the notion that wherever a story ends and begins it should always point to a wider, deeper, unsaid narrative.

Stories of the City was an exploration of how the city demands an intimate and unique relationship with its inhabitants. The audience travelled from Alex Preston’s Florence with its quiet sense of antiquity, to the bustling heat and social contradictions of Murzban F. Shroff’s Mumbai and finally on to the hard winters of Lynn Coady’s Alberta. Through their work the writers were exploring the characters of cities they know and love, both embracing and striving against cliché. Coady’s Alberta is a masculine and lonely working-class home for a woman punished by the natural, physical and psychological elements. Preston’s Florence is a beguiling city clichéd for its seduction of writers, yet uncontained. It reveals itself anew time and again. Likewise, Shroff’s Mombai is a city associated with poverty yet it sustains such a vibrancy of life. In Shroff’s words it is ‘like a benevolent mother it continues to give’ and there is a sense of eternal prosperity in that. Preston also introduced us to the Italian word ‘Scorcio’ which is roughly translated as ‘glimpse’. He explained that this was like the refiguring of a view seen in brilliant or changing sunlight. This seemed to be a very apt word for a city fleetingly showing its truth to the writer.

In Wales Arts Review’s own Fiction Map of Wales event, Cynan Jones, Francesca Rhydderch andRachel Trezise all read from their contributions to a collection which intends to not only show the diversity of Welsh short fiction but to give a sense of twenty-first century Wales. The recent Jerwood Prize winner and Frank O’Connor-nominee, Carys Davies, meanwhile, read the riveting South Wales-set, ‘On Commercial Hill, which could easily have fitted into the Fiction Map anthology [Carys will be contributing a brand new piece to our Story:Retold series later this year – Ed]. Set in different environments, both social and physical, these stories explored the ways in which people live within and identify with the area that they call home. All the stories were tinged by tragedy; they show a people living through the various struggles of social and emotional disenfranchisement. The following conversation, chaired by the book’s editor, John Lavin, focused on the genesis of each story, the difficulties or otherwise of writing about Wales, and the somewhat controversial pros and cons of being considered a ‘Welsh’ writer.

In Modern Voices, Jon McGregor, Laura van den Berg and May-Lan Tan followed a series of superb readings from their own work with a discussion based around their love for the short story. They agreed that it is a art form which lends itself to both experimentation and intensity. Its shortness means the author can demand more from the reader. Again, like the previous talks, the notion of framing is discussed. Van den Berg describes the experience of reading as ‘leaping from one cliff and ending up on another’ in the sense that the view can be extraordinarily different in such a short space of time. There is also something complete in the notion of the short story. Both a story and a collection can be read in one sitting and so can be experienced, considered and digested in its entirety. The panel agreed that this is what makes the short story form so exciting to both author and reader. The response is visceral, immediate. The panel then discussed which writers they particularly admired, the list including amongst many others, Alice Munro, Mary Gaitskill, Deborah Eisenberg, Simon Van Booy and George Saunders.

The Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award featured readings and conversation from Toby Litt, Tahmima Anam and Kevin Barry. Again the festival had managed to bring together writers of extraordinary quality, whilst at the same time offering different and distinct voices. Barry raised the roof with his story of a London Irish taxi driver; it was at once hilariously funny and heartrendingly tragic. Anam’s story was about factory workers and their struggles as women to protect themselves against the cultural, political and economic circumstances in which they lived. Litt’s work was more about the ontology of writing. It was the story of the first story, a mystical explication of the story of two hunter brothers in a Neolithic-like tribe. The post-reading discussion focused on the hard work and undeniable determination needed to be a successful writer. Barry was admirably candid; he described the pitfalls of ambition, and how you should always finish a story, even if all you want to do is ‘roll it into a ball and fuck it off a cliff’. This was echoed in the account of how Litt came to finally realise his story against the demands of a long promised deadline and the personal tragedy of his mother’s death. Anam described writing as an act of hubris which must be tempered with humility and self-doubt. The Short Story is the form which reveals everything and leaves nowhere to hide.

Deservedly the festival ended on the same high with which it began. It was an opportunity to share and engage with an astonishing collection of writers and readers from all over the world. Its ambition in both diversity and creating new partnerships was demonstrated time and again. Every event reiterated the truth that writing is a hard won treasure for authors and readers alike. The short story is an easily overlooked form but its power, completeness and sheer scope cannot be denied.

Photo of Piccadilly Waterstones LSSF display by Sira Pocovi.