Jon Gower looks at the current state of Welsh Short Story through the prism of Caradoc Evans.

Once upon a time Rhys Davies, the grocer’s son from Clydach Vale who became one of Wales’s finest short story writers suggested that…

When not ruined by the puritan thriftiness of silence the loquacious Welshman is a vivid gossiper, teller and creative weaver of tales, and his style is pointed with the best kind of malice, spite and derision.

I’m not sure if there are, in truth, good kinds of malice and spite, so I’ll take it that Davies meant a style which includes chiding, provocation and generally taking the jaundiced view. Fellow writer and critic Glyn Jones added a few more characteristics of what might be described as Welsh style in the short story:

‘Humour,’ he said, ‘is one of the most notable and constant qualities of Anglo-Welsh stories from the beginning. Satire is common too, or at least fun-making, and so is a sense of poetry, or a sense of language.’

The short story form has proved consistently attractive for a wide and able range of Welsh writers, and the roll call of the twentieth century short story happens to include many poets, from Glyn Jones and Alun Lewis through Dylan Thomas to Leslie Norris. The presence of so many versifiers should come as no surprise, because the short story is a slightly more rotund and therefore more capacious first cousin to poetry, making the same demands of its creator as writing a poem, in terms of concision, clarity and sometimes ambiguity. It is able, in turn, to generate similar energies, beauties and insights. By today, however, many of its best practitioners in Wales are women, and not usually poets – Deborah Kay Davies being the exception perhaps – so the roster includes Glenda Beagan, Catherine Merriman, Sian James, Stevie Davies and Tessa Hadley, all single mindedly fashioners of fiction rather than verse. In this respect the recent history of the Welsh short story follows an arc of expression similar to that seen in North America, where some of the very best short storyists are women;- Lorrie Moore, Annie Proulx and the peerless Alice Munro. It is, in itself, a story of both equality and talent, repeated on both sides of the Atlantic. Of course, there are writing men of gift and ability in North America too, and there’s been a recent outbreak of astonishing talent featuring Ron Rash, D.W. Wilson, Christopher Coake and Wells Tower.

In one of the most quoted books about the short story, The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story, the writer and critic Frank O’ Connor maintained that as a literary form it features ‘a submerged population group – a submerged population changes its character from writer to writer, from generation to generation. It may be Gogol’s officials, Turgenev’s serfs, Maupassant’s prostitutes, Chekhov’s doctors and teachers, Sherwood Anderson’s provincials, always dreaming of escape…

‘Even though I die, I will in some way keep defeat from you,’ she cried, and so deep was her determination that her whole body shook. Her eyes glowed and she clenched her fists. ‘If I am dead and see him becoming a meaningless drab figure like myself, I will come back,’ she declared. ’I ask God now to give me that privilege. I will take any blow that may fall if but this my boy be allowed to express something for us both.’ Pausing uncertainly, the woman stared about the boy’s room. ‘And do not let him become smart and successful either,’ she added vaguely.

This is Anderson…but it could be almost any short-story writer. What has the heroine tried to escape from? What does she want her son to escape from? ‘Defeat’ -what does that mean? Here it does not mean mere material squalor, though this is often characteristic of the submerged population groups. Ultimately it seems to mean defeat inflicted by a society that has no sign posts, a society that offers no goals and no answers. The submerged population is not submerged entirely by material considerations; it can also be submerged by the absence of spiritual ones.

Quantitatively, there have been lots of short story writers in Wales, especially in what might be called a heyday, in the thirties through to the sixties. The first four anthologies of stories from Wales, gathered in the thirties, forties and fifties, feature a total of 37 writers, who were often from Welsh speaking families living in a rapidly Anglicizing and industrializing world. In the thirties, in particular, the short story was very much in vogue, and a veritable raft of magazines existed to publish short form fiction, including the Welsh Review and Wales.

There have been many anthologies too. Tony Brown in his essay ‘The Ex-centric Voice: The English Language Short Story in Wales’ lists no fewer than 15 – starting with Welsh Short Stories, published by Faber and Faber in 1937. There have been others since his paper was written, not least the Bloomsbury collection Wales: Half Welsh, edited by John Williams which showcased what was in effect a new generation of writers such as James Hawes, Anna Davis, Trezza Azzapardi, Niall Griffiths, Malcolm Pryce, Des Barry and John Williams himself, although most of these were novelists in the main who turned to short fiction only infrequently.

They were writing about a different Wales: urban, fast, cynical, screwed up and mixed up. So different in their concerns from their predecessors. Glyn Jones, in his seminal work, The Dragon Has Two Tongues looked at what the writers of the apparent heyday of the short story wrote about. He suggested that sex was an infrequent theme, that the blue remembered hills of childhood loomed largely and that these short stories generally rejected organised religion. In terms of style he suggested, and this most tellingly, that ‘the Anglo-Welsh gift in literature is essentially lyrical and that longer works exhaust too soon the singing impulse.’

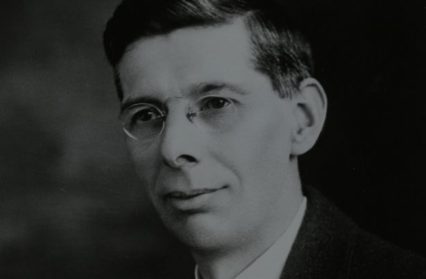

So the shopping list of the characteristics of the Welsh short story seems to be growing. Satire, material squalor, humour, a submerged population, a lyrical impulse and a vividly heightened sense of language we have aplenty in the work of Caradoc Evans, described by Gwyn Jones as the first of the modern Anglo-Welsh. There had been other writers, of course, some of them women as evidenced by the title of Jane Aaron’s collection Across The Valley: Short Stories by Women from Wales, c.1850-1950. Many of their works were set in the rural hinterland, penned with fondness and lit with sunshine. Unlike the septic tank of Caradoc Evans’s work. Because what used to be called Anglo Welsh Literature and is now the slightly less problematic but equally unsexy Welsh Writing in English begins with Caradoc’s calculated provocations, bilious tales full to the brim with a dark poetry rendered in staccato sentences.

The 15 stories in My People came out in 1915, charting the lives of Nell Blaenffos, Job of the Stallion, Sadrach Danyrefail and Old Shaci just as James Joyce had flickered life into characters such as Ignatius Gallagher, Father Flynn, Mrs Sinico and the con men Lenehan and Corley in his collection Dubliners which appeared a year earlier in 1914.

Whereas Joyce illuminated the Dublin middle class Caradoc Evans shone the arc lamp of scrutiny most dazzlingly on the rural poor. His splenetic and brilliant and brilliantly splenetic stories light up life in the borderland between deeply chapel-going Carmarthenshire and equally Nonconformist Cardiganshire as if with distress flares. He depicted a countryside populated by mentally and physically stunted sub humans, their crabbed lives blighted by a mix of avarice and ignorance. If William Faulkner depicted the Deep South then Caradoc Evans gave us the Deep West. The deep, Deep West.

There’s an abundance of material squalor out West in Caradocland but there is ample humour too, even if it’s of the most mordant kind. In one of Caradoc’s first attempts at a short story, published under the pseudonym D. Evans Emmott in the magazine ‘London Chat’ in 1907, there’s a glimpse of the splenetic humour of his later fiction as a deathbed scene proves to be a tad premature:

Preparations for death will always anticipate the coming of the dark angel. When Shacki Rees was ill, and expected to die, I called at his house and found Marged, his wife, putting on the fire the kettle which contained the water with which to shave the dead Shacki. She then stropped the razor. Shacki heard the ominous jingling noise the blade made upon the leather. Slowly he opened his eyes, one at a time. He ran white fingers through his stubby beard that had grown through his illness. ‘I think Marget,’ said he, stepping on to the floor, ‘that I’ll keep my beard, whateffer.’

We then had tea with the boiling water, because, as Shacki said, it was a pity to waste it. And Shacki lived for five years and three months after that.

By the time that early jaundice had festered into the bilious, black and out-and-out bloody marvellous stories about a loveless Welsh countryside collected in ‘My People,’ Caradoc had pared down his style as if he were using a threadwire saw, the sort you’d use to flense meat off a bone. The reaction to the collection wasn’t what you’d call mild. It was fervid, often very nasty and entirely over the top. Some critics, for instance refused to recognise works such as My People, and the later Capel Sion which followed hard on its heels in 1916 and My Neighbours of 1919 as being literature at all, dismissing them as sociology of some kind, meaning the nasty kind. A knife wielding critic slashed a portrait of Caradoc and might even have gone for the actual throat if the draper-turned-journalist’s jugular was within reach. The newspapers lashed and slashed, too. Caradoc was a ‘renegade’, with ‘an imagination like a sexual pig sty’ and one man even went as far as to suggest that he was a ‘a stormy petrel.’ A STORMY PETREL!!!!! That must have stung!

Famously the Western Mail branded Caradoc the ‘best hated man in Wales…’

It may be that Mr Evans spent his early days among some people of the kind he depicts; if so he seems to have lived in a moral sewer. For all his characters are repulsive, and designedly so.

It was indeed a very Welsh sewer and Caradoc seemed to enjoy nothing more than skinny dipping in it. He maintained that this was the way to plunge after the truth and indeed he marshalled robust defences of his work for the newspapers. After all, he argued, he was creating art, not documentary.

And one has to agree. It’s art and it’s great art. He is a master of concision and the deft and telling brushstroke. His characters – Jos Gernos, Sadrach the Small and the unfortunate Nanni – who lives on toasted rats having been fleeced by a Bible-seller – live and breathe most powerfully, powered by primitive and primal desires.

And great art lives by courting reaction. Welsh speakers and the three-times-on-a-Sunday brigade thought they were being unfairly pilloried. People listened in to the conversation of his repulsive characters and thought it was a parody of the Welsh language, a translation, or approximation, at the very least, of its grammatical patterns. But this was a language Caradoc created, and might have had more to do with the faltering English of the likes of the real life equivalents to Simon Idiot, Sara Glass Eye and Dull Anna.

Whatever the truth of his vision, his take on things, there’s no doubt that Caradoc could cram a lot into a few choice words. He could cram violence or horror, or a dismantling mix of both into a phrase or two. Such as the conclusion of ‘A Bundle of Life’: ‘Take this brat of sin with you now, little people,’ he said, ‘for he is not of my bowels.’ He was, clearly, adding power to language.

In his own mind Caradoc was justified in stripping away the veneer of false or mock respectability of the chapels, showing the beating heart of hypocrisy. His own mother fell foul of the regime of Y Sedd Fawr, the Big Seat where the deacons, those granite jawed moral arbiters sat in the relentless shadow of the pulpit. What had she done? One of Caradoc’s friends explained that ‘Like many other widow women, she was assessed to contribute to the treasury of the chapel. Lacking the money and having a heavy burden of young children, she would not pay, and was, according to custom, treated as outcast.’ It’s not surprising that Caradoc railed, in his fiction, against the seeming animal status of peasant women.

Because of his mother’s humiliation – and perhaps because he was himself too poor to train himself for the ministry – Caradoc had, perhaps, much more reason to have attack the chapels, the Hebrons, the Pisgahs and Gerazims. But it was one chapel minister against whom Caradoc’s scourge was most savagely wielded:

There was a man who might have been Hitler’s own schoolin. He was Dafydd Adams, minister Capel Independents, the red-whiskered wisp who sneaked after sin like a red tom-cat and slapped the pulpit Bible and broke its back every half year and spat through his spiky teeth in denunciation.

Dafydd Adams was the model for both Josiah Bryn-Bevan and Davydd Bern-Davydd, the near Stalinist dictators who ruled in Capel Sion.

In his lifetime Caradoc was feted and lauded and hailed by English critics as a masterful short story writer, as powerful as Gorky, as savage as Swift and as relentless as Zola. In Wales, though, his name was generally mud. It didn’t helped that he married posh – his second wife being the Countess Hélène Marguerite Barcynska, and for the prim and smug chapelgoers of course the divorce itself was viewed with the same distaste as drinking sewer water. But it wasn’t just Caradoc’s marital status that rankled, what really riled people was the work. My People continued to provoke. Even the police proffered opinion. The chief constable of Cardiff opined ‘I was for twenty years at Scotland Yard and I read most of the suppressed books, and My People is the worst book I’ve ever read.’ Indeed the book elicited such a reaction that on two occasions Caradoc had to have police protection when he was giving talks at Bangor and Cambridge.

Even after his death Caradoc was pilloried, his name further besmirched. In a leader column in the Western Mail in 1945 it suggested that ‘As a Welshman Evans’ disservice lay not in the fact that he deliberately caricatured his fellow countrymen but that he unintentionally and indirectly set an example to a rising school of Welsh writers in English, who instead of standing up and looking around prefer, as it were, to bend and peer under stones.’

Caradoc belonged to a small minority of that first wave of Anglo-Welsh writers whose early background was rural, not shaped by industrial society, yet he set a formative example to one rising star, if not the star of the Welsh short story, Rhys Davies.

In Davies’ autobiography Print of a Hare’s Foot he discusses his early stories and suggests that they ‘gave some flesh tints to Anglo-Welsh writing, of which there was none then except for the savagely bleak Caradoc Evans.’ Chronologically, Rhys Davies, the author of over a hundred short stories, followed on from the best-hated man in Wales, but thematically too, there is a sense that they’re exchanging batons, with which they’ll each charge the chapel citadels.

Meic Stephens, in his introduction to the three volume Collected Stories of Rhys Davies posits that ‘One of Rhys Davies’s difficulties was that he had few literary models on which to base his treatment of Welsh character and locations, and that is why so much of his dialogue and some of his plots call to mind the work of Caradoc Evans, the man to whom he was psychologically closest. He may not have had the latter’s vitriolic turn of phrase but he certainly strove for his economy of style and emulated his attempts at rendering the peculiarities of Welsh speech in English, at least in his early stories.’

But whereas Caradoc denunciated, flailing the Cardiganshire troglodytes in their closed, evil world, Rhys didn’t attack in the same way but chose, rather to shine a light under the stones of the chapel foundations, using humour to give him leverage.

Davies was also registering the urban abandon of the language he heard all around him as English speaking incomers with their bingo and beer overran the earlier worker communities with their Welsh speakers, their dour hymns and veneer of starchy parchusrwydd, or respectability. Rhys Davies, like Caradoc subverts the orthodoxies of Nonconformist life. Indeed his friend D.H. Lawrence suggested to him that ‘What the Celts have to learn and cherish in themselves is that sense of mysterious magic that is born with them, the sense of mystery, the dark magic that comes with the night…That will shove all their chapel Nonconformity out of them.’

Illicit sex could work its dark magic too. Especially on a Sunday. In Davies’ ‘The Dilemma of Catherine Fuschias,’ written in 1949, the dilemma in question is that her lover, Lewis the Chandler dies in her arms, after years of meeting him for sexual trysts just after chapel. Initially she gets away with it, but the reading of Lewis’s will is her undoing. First she is shunned and then cast out:

No one came to see her. She knew what it meant. The minister had sat with his deacons in special conclave on her matter, and he was going to tell her that she was to be cast out of her membership of Horeb.

And even when she decides to get out of Dodge, in this case the village of Banog, and decamp to Aberystwyth, it’s intimated that the chapel-gossip- grapevine will still reach out and strangle her there at the seaside. But Catherine Fuschias – a scarlet woman as is intimated by her very name – is not entirely exonerated by Davies. After all she is clearly prepared to deceive in order to clear her name. And fornicate on a Sunday, the last hymn echoing as Lewis the Chandler unsexily pulls off his drafers, his heavy woollen undergarments.

There’s chapel baiting too in Rhys Davies’s ‘Benefit Concert’ in which Jenkin the Collier finds out that Horeb chapel has a hundred pounds left over after a benefit concert to buy him a new artificial leg, leading to an almighty struggle between the one legged ex-miner and the chapel deacons.

But death is as much a character in Davies’ fiction as any chapel minister or deacon. For me, one of the finest and most affecting stories by Rhys Davies is ‘Nightgown’ which pivots on a mother’s sacrifices to keep her collier husband and her five sons fed.

When the men arrived home at midnight, boozed up, there were hot faggots for them, basting pans savoury full, and their pit clothes ready for the morning. She attended them in slower fashion, her face closed and her body shorter, because her legs had gone bowed. Mr Lewis next door said she ought to stay in bed for a week. She replied that the men had to be fed.

Her death comes with a savage inevitability, but when she’s laid to rest she’s wearing a new silk nightgown, which she’s bought simply for this occasion. The family see a new woman:

A stranger lay on the bed ready for her coffin. A splendid, shiny, white silk nightgown, flowing down over her feet, with rich lace frilling bosom and hands, she lay like a lady taking a rest, clean and comfortable. So much they stared, it might have been an angel shining there. But her face jutted stern, bidding no approach to the contented peace she had found.

The father said, cocking his head respectfully, ‘There’s a fine ‘ooman she looks. Better than when I married her.’

Rhys Davies once suggested that short stories are ‘a luxury which only those writers who fall in love with them can afford to cultivate. To such a writer they yield the purest enjoyment; they become a privately elegant craft allowing, within a very strict confine, a wealth of idiosyncrasies. Compared with the novel – that great public park so often complete with draughty spaces, noisy brass band, and unsightly litter – the enclosed and quiet short story garden is of small importance.’ But within that hortus conclusus, that enclosed garden, there is space for ‘something remembered with a smile, or a start of interest, with a pang or a pause of fear.’

If Rhys Davies was very productive when it came to crafting short stories then Gwyn Thomas – a noisy brass band novelist if ever there was one – was uber productive. In his lifetime Thomas penned no fewer than 200 tales and his collected stories, should they ever appear, will be a doorstopping novel to compete with the biggest tomes of Ken Follett or Vasily Grossman.

Gwyn Thomas had first started writing stories shortly after leaving Oxford in 1933 but he had to wait until 1946 to see the first of them published. In 1953 Malcolm Muggeridge gave him a commission for Punch magazine, the first of many magazine commissions. Other magazines such as Coal and Teacher followed suit.

The skills of concision and precision necessary to compress meaning, incident, description and plot into 1500 or 2000 words suited Gwyn Thomas. This was, after all the master of the bon mot and rapid fire badinage, whose work is bright with lovely lines, sentences such as ‘Our foreman says that I am so bad a hand at bricks that I ought to sign articles with the Eskimos and specialise in igloos where the walls are curved in just the way I curve them and not meant to outlast a good warm spring.’ Like Rhys Davies’ tales the twenty three Selected Short Stories of Gwyn Thomas contain death aplenty. By page 2 of the opening ‘And a Spoonful of Grief to Taste’ we’ve had death mentioned five times with a couple of grim reaping scythes sweeping through to keep everyone on their toes. Almost every story features a funeral suit or a dab of grey grief. ‘My Fist Upon the Stone’ opens thus: ‘Life did not change much for Rhianedd Hicks and her son Abel after the death of her husband John.’ The next story, ‘The Leafless Land’ ends with the line ‘To despair of helping him find it, that is death.’ Another story ‘takes the shroud off our regrets.’ Death is pervasive and prevalent, and funny. Death, in the huddling and frenetic life of the south Wales terraces, was a commonplace. Those scythes glinted swiftly underground, just before the roof caved in, just as surely as they harvested the infants in their brief mortality.

Gwyn Thomas managed to shoehorn writing time for stories even when he was hard-grafting it and writing novels. At the same time he was writing Sorrow for My Sons Gwyn Thomas was writing scores of them, of the sort described by Thomas’ biographer Michael Parnell as ‘intense, powerful and melodramatic, rather in the manner of Caradoc Evans.’ One, called the ‘Agony in the Skull’ shows a young woman, spent from the business of looking after a family on the dole and in the throes of debilitating poverty, not to mention a pregnancy she certainly didn’t want, who faces a further blow when the pig dies. Her husband leaves the gate to the sty unlocked and the animal crashes to its death at the base of a ravine.

Esther limped towards the ravine. She stumbled. Her hands landed in a steep, black puddle…Esther’s mouth came near. Her head-nerves jangled. Hunger, weakness, a great insensate wanting to vomit, to have her toes forced upwards through her body to between her teeth. She wanted to dip her lips into the festering pool and fill herself with it. She sobbed in a musical singsong.

She did not get to her feet. She continued to crawl. She stared in front of her, avoiding the broken jars and bottles that strewed the ground, wanting to tear her flesh open.

She peered into the ravine. Menna lay at the bottom…Her head was twisted. Blood streamed from her distended belly. A rat that had crawled out of the culvert sniffed at her leg. Esther wanted to slip over the ravine’s edge and strangle the life out of that dirty, brown rat that dared defile the dead, white Menna.

The trials of Esther, not to mention the whiteness of death when it comes, brings to mind the silk of a nightgown draped around that other long-suffering woman in Rhys Davies ‘Nightgown.’

So, there are echoes here of both Caradoc and Rhys Davies. The staccato, clipped sentences are neatly redolent of My People and My Neighbours with all their rural brutality.

There are echoes – albeit very very distant – of Caradoc, Gwyn and Rhys in the work of Rachel Trezise, the poster girl for the latest generation of Welsh short story talent. One definite nod to the writers who commandeered the valleys territory before her is to be found on the very first page of her dancing collection, Fresh Apples, which won the inaugural EDS Dylan Thomas Prize. Here we meet a character whose full name is Rhys Davies John Davies, named, as the story suggests ‘after a gay Welsh poet.’ The author Rhys Davies, was, of course, gay, and thus an outsider, a member of one of O’Connor’s submerged communities.

But there are other links with Rhys Davies. His tales are full of women, often the headstrong type and it is little surprise to learn that Emma, Madame Bovary was one of Davies’ literary heroines. And as we know they’re also full of death, tales so drenched in it it’s as if he’s steeped them in embalming fluid to preserve them forever. Davies is fascinated by death, so that his work is full to the gills with fatal accidents, bereavements, widows, murders, corpses, coffins, wreaths, legacies, funerals, cold ham and mournful hymns. ‘Myself, I favour a dark funereal tale’ he suggested in the preface to the Collected Stories of 1955, ‘but not always.’

There are strong women aplenty and oodles of death in Trezise’s Fresh Apples. The eponymous opening story, shot through with arson, paedophilia and rape, ends with the sixteen year old heroine of the piece in two minds about death, even as she lies down on the railway tracks, like the Perils of Pauline filmed at Penygraig, or the Rhondda’s answer to Anna Karenina, the rails cutting into her hamstrings.

I wasn’t sure if I wanted to die. No I didn’t want to die. Not forever anyway, only until it was over, until it was all forgotten. I remembered Geography classes in school, where the teacher would talk about physics instead because he was a physics teacher really and we’d get bored and stare down here to the track and talk about how many people had died here. Kristian said there was a woman who tied herself in a black bag and rolled onto the track so that when the train came she wouldn’t be able to get up and run. I didn’t need to do that. I stayed perfectly still. Didn’t even slap the gnats biting my face. When the train came, the clackety-clack rhythm it made froze me to the spot. I just closed my eyes. When I opened them again the train had gone, gone right past me on the opposite track and splashed my legs with black oil. I don’t know now if I’m brave or stupid. It isn’t easy to be sixteen, see, and it isn’t that easy to die.

The Wales, or at least the south Wales, Rachel describes is very far removed from Caradoc’s world of chapels. This is a country, after all, that went from being one of the most religious countries on earth to one of the most secular on earth in just a few generations and as we’ve already heard populations can be submerged by the absence of spiritual ones. Unemployment replaced the stamp of workers’ boots as the hooters blew. Heroin replaced faith, individual isolation replaced community bonding. There was material squalor and no point in a young woman in the valleys having hopeful dreams. But Rachel did…

In a biographical fragment Trezise says: ‘At the age of fifteen I decided to become an artist. Not just any artist of course. No weak, pretty water colours for me. I didn’t want to be Monet. Oh no! I wanted to be Pollock or Munch or Lichtenstein. I wanted to be Isadora Duncan! Monroe! Hendrix!’

Reading Rachel Trezise it’s hard to see which one of these she’s become, or most nearly aligned herself with, or, rather, it’s not worth asking because she’s become an artist in her own right. The language she employs isn’t in the lyrical register of Caradoc Evans or Rhys Davies, and neither is her shopping list of stylistic features much like the writers who preceded her. No satire, no malice, spite or derision – even of the allegedly best kind. It’s the language of a gritty realism, a streetwise demotic. But when the choice words appear, cut through, they’re enough to stop you in your tracks. Here’s the beginning of ‘A Little Boy:’

The mattress underneath her was cold with sweat. She dare not move. She just lay there, crunching her pelvic floor into a painful crease to save pissing on the sheet. knowing, even in the dark, that it was going to be a malicious day.

A malicious day. A deliciously well-chosen adjective which rather leaps out at you. And her debut collection is full of such felicities. ‘The wind shook the daisies on the hill back and forth, their heads nodding at some warning sent from the atmosphere.’ A boy has ‘a washboard torso.’ The twisting branches of winter trees ‘seemed to grasp rather than dance.’

The Stanford-based academic Franco Moretti, described as ‘the great iconoclast of literary criticism’ has been pioneering new approaches to books, suggesting ways in which scholars should start counting, graphing and mapping them. His books are full of charts, maps and diagrams. There’s an interesting cartography to be drawn up which would show the two Rhondda valleys as epicentres of the English short story in Wales, much as the slate quarrying areas of the north west spawned so many Welsh language writers such as Caradog Prichard and Kate Roberts.

So Rachel Trezise lives just a crow hop away from Blaenclydach, a side valley of the Rhondda Fawr where Rhys Davies was born, his parents keeping the shop grandly known as the Royal Stores. The pyrotechnic, often hyper-oxygenated stories of Ron Berry were written by a man who left school in Blaen-Cwm at the top end of the Rhondda Fawr at the age of fourteen, going to work in local mines. Gwyn Thomas was born in Porth. The Rhondda valleys meld together as a creative nexus, a veritable fiction factory.

For writers such as Rhys Davies the terraces of the Rhondda proved to be fecund source of stories, although as he grew older – and as the gap between childhood event and memory’s account of it widened – his work could stray towards parody, even burlesque – certainly work that suggested that a weaker signal was now pulsing through from the remembered past to his pen.

A Moretti style mapping exercise of the short story in Wales would surely be revealing, especially were it in colour, the sort of thing that shows economic activity in Europe, with northern Italy glowing a furnace red along with a throbbing Catalunya. So you’d have the Rhondda, epicentre of it all, hauling out story after story on the pit head wheels of imagination.

Merthyr, cradle of the industrial revolution would have Glyn Jones and more recently Des Barry, raised on the Gurnos estate, whose stories about Merthyr scams and cons have graced both Granta and the New Yorker.

There’d be gossamer connections from here to Utah and Brigham Young University where Leslie Norris taught and told stories about his native Wales and about the pioneers of America, such as the ‘sweet-tempered stories’ gathered in Norris’ 1988 collection, The Girl from Cardigan. This is what the New York Times had to say about them: ‘To a short-story reader whose expectations, are of ambiguity, irony and compactness of form, Mr. Norris’s tales present a surface bafflingly benign, amiably conversational, in which small-town vagaries are dwelt on fondly, and nesting herons and lighted shop windows are described with attentive accuracy.’

Cardiff would be represented by John Williams’ tales of new Tiger Bay, perhaps, while a mere kingfisher flight away from Hay-on-Wye it would mark, with quiet green pennants, say, the south Herefordshire borderlands where Margiad Evans penned the sort of stories that featured in her collection The Old and the Young, first published in 1948 with their flinty descriptions of hard rural lives overshadowed by war.

So the concentric circles, the ripples on the map would emanate out from centres such as the south Wales valleys to far flung locations, including the India, and indeed the Palestine depicted so vividly in Alun Lewis’s masterpiece ‘The Orange Grove,’ one of the half dozen stories by the soldier-poet, which, opines the poet Owen Sheers words, are ‘capable of the most lambent and lyrical touches without losing focus on the lived and physical.’

Little by little the contour lines would contract and tighten, showing concentrations of authors and their subject matter, molehills accreting to become peaks of fiction, showing connections between writers and places, and overlaps in inspiration and examination.

And such a map would also locate those places which have attracted writers from outside of Wales, to write short stories set here. There’s a long tradition of penning such tales, some predating Caradoc Evans, of course. Some of the most intriguing are to be found in a favourite anthology of mine. The Magic Valley Travellers: Welsh Stories of Fantasy and Horror in its bright canary yellow Gollancz livery, features a wonderful array of tales such as ‘The Corpse Candle’ by American folklorist Wirt Sikes and another by the author of Frankenstein, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. Called ‘The Invisible Girl’ it’s set, Gothically enough, around a ruined tower on a ‘bleak promontory overhanging the sea, that flows between Wales and Ireland.’ Mary and her partner, the poet Shelley ‘journeyed with much delight through the great fastness of Wales” and is, indeed one of several short stories she wrote with a Welsh setting.

But if one charted the production of short stories over the years in the form of a graph I’d imagine it would show a steady decline. The glut of magazines from the golden decades of the 1930s, 40s and 50s is itself a sort of golden age. The story recently has been one of retrenchment. The demise of the magazine Cambrensis was a body blow and such developments as Planet magazine going quarterly reduces another outlet for short fiction. Publishers are wary of the form, with conventional wisdom saying that story collections don’t sell as well as novels. Nowadays the appearance of a new collection of short stories in Wales seems like an event rather than a regular occurrence. Which I find curious. At a time when our lives are faster and attention spans shorter it should fit in well with the pace and demands of modern life.

Prizes help, of course, be it the new Costa prize for the short story or the EDS Dylan Thomas Prize. The inaugural prize of £ 60,000 was won by Rachel Trezise. As we’ve seen she is sharing a physical territory with the male writers who staked it out, and mapped it before her, but it seems as if her way of doing so marks out a new beginning, as proper art is meant to be. So, in Fresh Apples there’s plenty of adolescent sex, underage drinking, ever present drug use, or abuse which help deepen the confusions of trying to make one’s way through the world. Whereas Gwyn Thomas depicted lives which were fundamentally grim the communities around them were protective and embracing but the characters in Trezise’s broken places have to fend for themselves. The communities themselves are broken, post-industrial damaged goods.

But it’s the language that truly demarcates. Trezise’s work seems to confirm a suggestion by the writer and anthologist John Davies, that ‘a certain period of romanticism is over.’ In Fresh Apples social realism has replaced the mythopoetic, or if there are myths they come from the maw of American commerce, such as the trick-or-treats of Halloween, Spiderman and Frankenstein, all replacing the Fari Lwyd of ‘Welsh Folk classes at the Sixth Form College.’ The stories signal the complete separation of the urban experience from the rural way of life, unlike, say Ron Berry who often sent his characters up to the moorlands above the terraces and who penned a fine little nature treatise called Peregrine Watching.

Her work is largely stripped clean of all evidence of what Alun Richards described as ‘the need of some Welsh writers writing in English to emphasize their difference from English counterparts by exaggerations of speech and the whimsicality which gives the lie to thought.’ Often the demotic of the language is cool, detached, knowing bringing to mind so many modern American stylists. It’s there in the work of other talented writers, too, such as Deborah Kay Davies. It’s a signal difference. Earlier generations of writers had the Welsh language informing or dancing under the cadences of their sentences, or in the case of Caradoc Evans clog dancing under their sentences. Even Gwyn Thomas admitted the influence:

Everything I have written…has had at the back of my idiom the language of people who have been talking a language for 2000 years that I never knew… This is rather uncanny and weird, but is something to be accepted because I will never get rid of it all.

Trezise has no such obvious connect. The Welsh language doesn’t seemingly add its rhythms to the undertow of her sentences.

But of course Rachel Tresize is just one – albeit one of the most gifted – of a still growing bank of writers who engage with the short story. Its shards and fragments, its incendiary illuminations and blurts of epiphany reflect the complicated small country we inhabit. There is now a greater diversity of voices, and, thankfully, all talk of the death of the short story is still a tad premature. It’s a form that suits the age, of speedy lives and shrinking attention spans and throughout the modern age the Welsh have been pretty good at it.

Next year will see the publication of an anthology of short stories under the aegis of the Library of Wales. It’ll be a chance to take stock. To see the new voices jostling for place, edging out the old guard. To be sometimes dazzled by the flares of genius in the work of often dissimilar fabulists such as Caradoc and Rachel.

Glyn Jones suggested that one of the symptoms of being a short story writer is a that you have a trivial mind and a brooding heart.’ I’d say that some of the other symptoms are a hapless and incurable love of language and its myriad possibilities. A desire to make the lonely voice sing lyrically true in garret and garden flat, in decaying towns in a poor country, in what Bruce Springsteen called the Darkness On the Edge of Town. To concertina meaning and hopes and the fitful and sometimes fatal desires of us all into a couple of thousand words or so.

We are fortunate in Wales to have had a distinguished litany of short story writers to set off their flares of language, to show us things both glaringly obvious and deeply hidden. Caradoc. Alun. Alun. Leonora. Deborah. Dylan, Glyn. Glyn. Othniel. Rachel. Craftsmen.Grafters. Writers. Satirists. Vivid gossipers. Illuminators all.

As one commentator put it: ‘Words, words, words, how peculiarly they enchant you when you are writing of Wales. How they beguile the unwary as he struggles to capture the magic and mystery of the country. How they run away with you like sun on slippery glass, like thoughts on a drunkard’s dream or mists on the dark mountains of evening…’

But I’ll end with a beginning. A story called ‘Honey’ by our National Poet Gillian Clarke opens thus: ‘Only the story knows the when and the where of it. It makes us an offer: enter the myth and it’s yours. We can make our lives from the story.’

It’s a beautiful inversion. For just as writers make their stories from the stuff of life, so too can they make our lives more complete, enriched in both texture and understanding, standing proud on illuminated ground.

Delivered at the Hay Festival 2012: kindly supported by Literature Wales.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis