Children’s author Nicola Davies explores the processes involved with her Shadows and Light series of books, and how she works her stories through the collaborative experiences of working with illustrators.

Actors are not the only people to get type cast. It happens to writers too, perhaps it happens to writers even more. Once you are placed on a particular shelf in the bookshop or in the library it’s really hard to jump off. And the more successful you are the harder it is. I know writers – hugely successful and bestselling in their genres – who long to write something else. But with the weight of their sales figures pressing down on them, getting off one shelf and onto another is all but impossible.

Fortunately, I’ve never been that successful. I’ve never had a breakthrough book, I’ve never had a bestseller. What I have had, is just enough success to keep me in business. Enough sales to make publishers let me do another book, and with just a little wriggling and persuasion, I’ve been allowed to do books that are not exactly alike. I’ve done nonfiction, poetry, and fiction – all for children and so well below the media radar that I can play with the genres: nonfiction that’s really poetry, fiction that’s really fact, poetry that flirts with verse, iambic pentameters and rhyme.

Fortunately, I’ve never been that successful. I’ve never had a breakthrough book, I’ve never had a bestseller. What I have had, is just enough success to keep me in business. Enough sales to make publishers let me do another book, and with just a little wriggling and persuasion, I’ve been allowed to do books that are not exactly alike. I’ve done nonfiction, poetry, and fiction – all for children and so well below the media radar that I can play with the genres: nonfiction that’s really poetry, fiction that’s really fact, poetry that flirts with verse, iambic pentameters and rhyme.

Until recently I was happy that almost everything I wrote had its toes in the real world. Fantasy and fairytale were places I visited for recreation, not spaces where I felt I could work. I’m not sure exactly what changed. Maybe I just felt that after 20 years I was ready to fly without the stabilisers of fact.

Maybe seeing storytellers like Hugh Lupton and Michael Harvey made me want to see my own audience spell bound and mesmerised. And maybe I wanted to write something a little darker, a little more ambiguous than the constraints of natural history would allow.

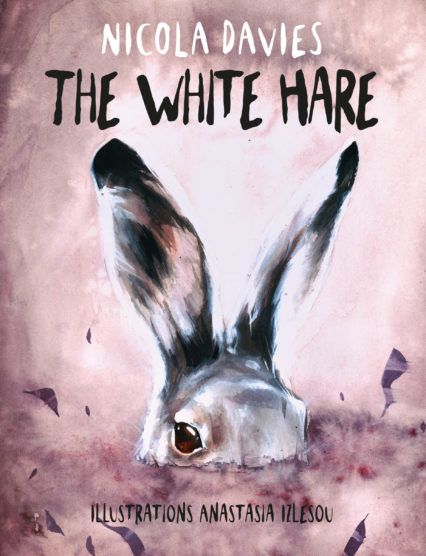

Whatever it was, I wrote a story about a magical transformation: a girl, traumatised and threatened by male violence who escapes by changing form. It was a huge liberation. The story just came, out of my fingers onto the page, as if it was flowing in my blood. And when I told it, and saw my audience transfixed, hooked, quite literally holding their breath, I felt I’d opened a door in my mind that I never wanted to close. I’d never had a problem connecting with audiences, but that level of connection, visceral and transporting, was a new experience altogether.

It isn’t so much that I write these stories for older children and adults – I’m still careful not to include overtly sexual material, I still want my work to be accessible and acceptable to the widest possible age range (I don’t see my picture books, for instance, as the preserve of the under eights). It’s more that I’m writing them to get access to a different part of my audiences’ hearts and minds. ‘Fairy Stories’ – which is the simplest way to describe what I’m writing in the Shadows and Light series and in two forthcoming and much longer books – access something deep and old within us; that collective unconscious of which Jung wrote about, which I remained unconvinced about until now.

Writing stories for me is always a process of discovery. I don’t know where exactly I will end when I start. I begin with my characters and see what it is they do, what they want, what they need. I discover them through writing and thinking, through imagining. Sometimes I learn things about them in moments of deep realisation, as if remembering something I’ve always known. These aspects of the stories and characters are often things that I then discover in other places, in the retellings of the oldest tales. For instance, I have a character in my next ‘fairy story’ who gives birth to a walking, talking baby after just a few weeks of pregnancy. Almost the day I’d written that, I found that there was a character in the Mabinogion who gives birth to a child that walks on his first day, after a very short pregnancy. Thinking more about this I realise that it was a dream I’d had whilst I was pregnant, and I suspect if I ask around, I’ll find other women who’ve had it too.

Writing stories for me is always a process of discovery. I don’t know where exactly I will end when I start. I begin with my characters and see what it is they do, what they want, what they need. I discover them through writing and thinking, through imagining. Sometimes I learn things about them in moments of deep realisation, as if remembering something I’ve always known. These aspects of the stories and characters are often things that I then discover in other places, in the retellings of the oldest tales. For instance, I have a character in my next ‘fairy story’ who gives birth to a walking, talking baby after just a few weeks of pregnancy. Almost the day I’d written that, I found that there was a character in the Mabinogion who gives birth to a child that walks on his first day, after a very short pregnancy. Thinking more about this I realise that it was a dream I’d had whilst I was pregnant, and I suspect if I ask around, I’ll find other women who’ve had it too.

Thinking back to the girl who becomes the White Hare in my first of the Shadows and Light series, it seems to me that the many magical transformations in traditional stories are responses to impossible situations; a metaphor for the powerless escaping from oppression and violence by taking their minds elsewhere. I find myself using them all the time – in Elias Martin, and Bee Boy and the Moonflowers and in my new story that doesn’t even have a title yet.

Do these shared imaginings show that human beings have some deep, otherworldly spiritual connection? This is where I retreat to my scientific background. I think what the common themes and images that recur in the oldest, deepest stories from around the world, show that our bodies and brains share similar hard and soft wiring, and throw up the same patterns. If these have a meaning I don’t think we have any way to divine what it truly might be. But they do have an effect, and that is to give us a sense of connection to each other. That is perhaps the reason why people love to hear these stories of the deepest shadows and the brightest light, and why I will go on writing them.

You can find out more about the Shadows and Light series here.