Drawing on the collections of the George Eastman Museum in New York, and in partnership with Cardiff University and Wales Arts Review, photography scholar Alix Beeston seeks to reimagine how women have been pictured through the medium’s history in a new Instagram project, Object Women.

The nineteenth-century photographer Mathew Brady is usually remembered for his and his studio’s documentation of the American Civil War—battlefield scenes that captured its bloody realities with a stark and unprecedented clarity. The images produced by Brady’s studio brought the Civil War home for his contemporaries, but they also bring it home for us, playing a crucial role in shaping our cultural memory of this formative event in U.S. history.

But before and after the war, Brady worked as a portrait photographer out of his New York studio. As I’ve been trawling the holdings  of his work in the George Eastman Museum collections, it’s one of his ambrotype portraits, taken at the cusp of the War, that has grabbed my attention.

of his work in the George Eastman Museum collections, it’s one of his ambrotype portraits, taken at the cusp of the War, that has grabbed my attention.

The ambrotype was a technology with a short life span. Initially patented as an alternative to the daguerreotype, the first commercially successful photographic process, it was soon replaced by other forms such as the albumen print and tintype. In the case of Brady’s ambrotype, we don’t know who the couple is, or exactly when the image was taken. And, when the portrait was donated to the Eastman Museum’s collection in 1963, it arrived without a housing. As a result, this photographic object makes it possible for contemporary viewers to see the ambrotype’s technical trick: a collodion on glass negative is deliberately underexposed, so that the negative image appears as a positive image when it’s displayed against a dark background.

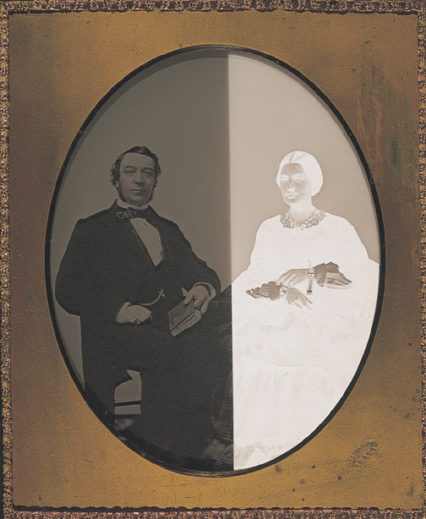

One particular digital image of the portrait unveils the negative-positive duality of the ambrotype process. Taken for educational purposes, this modern-day image shows the portrait of the couple bisected: we see the man against a black backing, but the woman is left backless and bare.

There’s an elusiveness about this contemporary image of an historic object that seems to parallel the effect of the woman it pictures, as she sits, prim and proper, in bright whiteness. She looks like a weird ghost, both visible and invisible, shimmering in and out of sight. This ghostly apparition emerges as a result of the duality of Brady’s medium. Looking at her, it’s easy to see why the ambrotype was decried as “ghastly, dead, inanimate, flat,” to borrow the words of one photographer writing in to the editor of American Journal of Photography in 1861.

There’s an elusiveness about this contemporary image of an historic object that seems to parallel the effect of the woman it pictures, as she sits, prim and proper, in bright whiteness. She looks like a weird ghost, both visible and invisible, shimmering in and out of sight. This ghostly apparition emerges as a result of the duality of Brady’s medium. Looking at her, it’s easy to see why the ambrotype was decried as “ghastly, dead, inanimate, flat,” to borrow the words of one photographer writing in to the editor of American Journal of Photography in 1861.

Yet I am drawn to Brady’s photograph specifically in its bisected form—that special view afforded by the accident of the ambrotype’s unhousing. While the learned husband, book in hand, is solid, firm, and well-defined against the black backing, the visual blank that is his wife seems to me endlessly suggestive. It’s as if the negative-positive bifurcation of the ambrotype is a hinge for the kinds of oppositions and dichotomies that have conventionally distinguished husbands from wives, and men from women, in Western culture. It is he who has substance; she who is all surface. It is he who has personality, who is somebody; she who is anonymous, a nobody. He stands for action—he does things, like, say, read a book; but she is passive, a body to whom things are done, just as the removal of the black backing makes her into an abstraction, a flimsy, paper-thin, bleach-white silhouette. Or, in the words of the disgruntled letter-writing photographer in 1861: dead, inanimate, flat.

Brady surely didn’t mean for all this to be contained in his double portrait. After all, the ambrotype was meant to be seen as a fully positive image. But over the last few years, in my research into the representation of women in visual culture, I’ve been trying to find new ways to analyze photographs and photographic technologies that are confounding or surprising in their meanings. Photographs, that is, like this unhoused one, with its intriguing, frustrating vagueness, reflected in the literal indistinctness of its female subject.

For many years, art critics have focused on how the camera has been turned on women in ways that objectify them, turning them into objects of male fantasy and desire. “Men look at women,” wrote the late, great cultural theorist John Berger. “Women watch themselves being looked at.” These famous phrases take on a new resonance in our cultural moment, as women are saying #metoo in every language, protesting the full spectrum of gendered aggression and violence—which is arguably underwritten by the idea that women are valuable above all for what they look like, for their surfaces, their skins.

But can we look in new ways at photography’s many inanimate, ghostly female bodies? What if the object woman, the objectified woman, can be re-envisioned as the woman who objects to her own objectification? What if she’s not (or not only) inanimate or ghostly, but instead lively, provocative—even funny?

I’m not suggesting that we should ignore how women’s bodies in photography often do sit with the long history of the female muse caught under the objectifying gaze of the male artist. But I do think it’s worthwhile to look at these bodies with fresh eyes, to see how they might also trouble and complicate that history, even if only in limited and symbolic ways.

This is the context for the new online project that I’m launching on Instagram. “Object Women” will be released over a few months beginning on the 1st of March. Drawing extensively from the George Eastman Museum’s collections, and building on previous exhibitions such as The Gender Show, it will feature one image a day, Monday to Friday, moving from the beginnings of the photographic medium to the present. Each image will be accompanied by a brief written reflection exploring its depiction of women, with a view to how photographs often make us aware of their own moment of encounter, that moment when photographer and subject meet. This encounter between observer and observed is not always as straightforward or unilateral as we might expect.

I look again at this digital rendition of Brady’s ambrotype, laying bare the technology’s negative-positive structure. The woman is subtracted from herself, pictured as the flat, dead icon that so much of art history assumes woman to be. But I remember that the word subtraction has a Latin root with a double meaning: to remove, to take away, but also to withdraw, to pull back. Maybe, then, we can interpret the stolen, abstracted body of this woman as an evacuated one. Maybe she’s running away, evading our view, and so curtailing—refusing—her own objectification.

Object Women launched on Thursday 1 March 2018. You can see the project as it unfolds at this link or by following it through your Instagram account.

Dr Alix Beeston is a Lecturer in English at Cardiff University. Her first book, In and Out of Sight: Modernist Writing and the Photographic Unseen, is available now from Oxford University Press.