In this summer of seething politics and digital fervour Adam Somerset relishes the spark and bite of the long-form print essay in his review of The Phenomenon of Welshness II.

It has been a sobering season for digital media. Guardian Media Group, its weight thrown behind a cyber-advertising business model, cut its endowment by another seventy-eight million pounds over 2015. Owen Jones in an article of 31st July, to his credit, gave to the Opposition’s internal debate the blast of rigour and questioning it needed. If a former Premier had a liking for unveiling policy via the Jimmy Young Show it was because Radio 2 had fifteen million listeners. Seventy-eight percent of voters, says Jones, gets its politics via snippets of television. That is at least seven times greater, according to the latest study, than the tuners-in to micro-bloggery. Politics solely via social media is a politics of vanity, slivers of agreement that give an illusion of a great consensus.

And, of course, a shrillness of content predominates. The comments against women parliamentarians do not bear repetition. A Labour peer, and the Party’s most eminent living historian, writes an article on Keir Hardie. The response is “lily-white democracy hating Zionist crawling out of the Labour woodwork”. This is not a private blog but a public comment on a newspaper site. It is less the venom or the scared anonymity that depress than the sheer solipsism, the makers of blurts who blurt only for themselves

And, of course, a shrillness of content predominates. The comments against women parliamentarians do not bear repetition. A Labour peer, and the Party’s most eminent living historian, writes an article on Keir Hardie. The response is “lily-white democracy hating Zionist crawling out of the Labour woodwork”. This is not a private blog but a public comment on a newspaper site. It is less the venom or the scared anonymity that depress than the sheer solipsism, the makers of blurts who blurt only for themselves

All of which is prelude to reminder of the value of the true essay. Essayists are makers of a rich seam within the realm of letters, at their best probing, informed, irreverent. At their peak essayists meld the authority of judge or teacher to a sense of comradeship of a life companion. Essayists who count are not so many in number and Siôn T. Jobbins is among of them.

Jobbins’ essay collection dates from 2013 and the writings themselves are reprints from Cambria Magazine. From the perspective of the winter of 2011-2012 he anticipates Scotland’s Referendum. He fears a rump of forty MPs for Wales will make his country like Montenegro. Of course, it has turned out differently. Barnett is set in stone, even over the protests of its creator that it was a temporary piece of expediency fashioned decades ago.

Jobbins closes his essay on Scotland with the line “It’s time we got to know the Scots better.” His start point is always culture, the midwife to politics. He points to the thinness of contact between the nations. Thirty towns of Wales are twinned with Breton counterparts, hardly one with a fellow member of the United Kingdom. He also knows his history, the losses of Rhedeg and Gododdin in 635 and 638 respectively. He looks to the battle of Falkirk in 1298 to cite the lack of common cause between the two nations. The army under King Edward had twelve and a half thousand foot soldiers. In the Jobbins’ telling ten and a half thousand were from Wales.

As for language Jobbins finds a Scot appointed vicar of Roath in 1815. John Coupar writes to the First Marquis of Bute in astonishment that many of his parishioners are not speakers of English. Jobbins is ever the punchy essayist. His trawl across the national differences embraces not just neeps and Irn-Bru but law and media. “They have proper grown-up media and press,” is how he phrases it with provocation.

Jobbins defines himself as thwarted in politics. That may be, but aspirers to office are many, whereas essayists of spice, vim and pungency are few. There is much in the twenty-eight essays in The Phenomenon of Welshness 2 to relish. The book divides in five sections “People”, “Places”, “Politics”, “Past Studies” and “Prints, Programmes and Portals”. It is a useful division but the point of the essayist is that he roams. The essay makes connections. Remembering the Seimon Glyn Affair Jobbins fuses culture, politics and polemic. He calls Glyn “a little known Plaid Cymru councillor in Gwynedd.” His concerns about linguistic dilution send Jobbins to write of “Labour’s dank hypocrisy” and “Plaid Cymru’s leadership had a breakdown.”

Politics and culture fuse again when Jobbins recalls Meurig Llwyd, the Venerable Archdeacon of Bangor, penning an article on the commonality behind the monotheistic faiths. Y Llan had a circulation of no more than five hundred but nonetheless his editorial decision impelled his sacking. Jobbins denounces the statement from a then Assembly Government Minister expressing her gladness. Her stance over a plurality of expression is to Jobbins “truly shocking.”

Labour does not earn many good points in the Jobbins book. On the campaign for an internet “dot-cym” domain he declaims, “How dare a man who was the First Minister of my country tell me…?” A view about S4C expressed by Chris Bryant in a Commons debate in May 2004 elicits the response, “This is a bizarre statement that defies all logic.”

Good politics are based on good history and Jobbins knows a lot of history in detail. He knows the political status of Monmouthshire from the laws enacted by the Tudors in 1536 and 1542 to the decisions enacted by unnamed civil servants within Harold Wilson’s government of 1966. He reveals that the ecclesiastical border of the Church in Wales is not the same as the political border. He finds a reference to gays in the Laws of Hywel. Henry Brooke is revisited in the Commons in March 1959 on the subject of the Welsh flag.

The essay is the person. It is not confession, but the practised essayist threads his writing with the occasional snippet of autobiography where it is pertinent. Jobbins’ grandfather had an uncle who was at Rorke’s Drift. He recalls that his Internet domain campaign was spurred by reading that the Catalans had gained “dot cat” for themselves. It is revealed that this most passionate of Welshmen has in fact Zambia as his country of birth.

Essays that count juggle big ideas with fine detail. He writes of the transmission of the existentialism of Paul Tillich into a Welsh context by J R Jones. Seven pages follow the tradition of the “calennig” from its origins and aesthetics to modern memories from Keith Morris and Goronwy Edwards. He quotes from a study “Why Nations Fail.” Success is the result of good management of a state – “the policies they take, not geography, not topography, not climate, not culture.”

He remembers campaigners for S4C as “the real heroes… the cagoule-wearers in horrible C&A slacks, not the mid-Atlantic druggies” – this last reference is to Ammanford’s most famous player of the electric viola. Later supporters of the channel are “the usual duffle-coat wearers from Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg.” When he sees another programme of hymn-singing he writes “the surfing viewer is sure to label the station a comfort zone for coffin-dodgers.”

Jobbins comes up against a “particularly useless and lazy civil servant… backed up by a dire report from the Cardiff Business School.” The whole world admires Edinburgh – it looks the part of a capital. In Cardiff Bay Jobbins sees “a heartless Slough-by-Sea.” The city itself “looks like a second division English provincial city – Nottingham, Reading – and acts like one. It has less international traction than Reykjavik, which is a slightly bigger version of Carmarthen.”

It is not true but that is not the point. In truth, to be on a Spring day near to the Temple of Peace, to see the dome of the National Museum in one direction, the stirring contour of the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama in another is to be in, and to feel, a place of wonder. But every culture is the doughtier for its sharp-stinged wasps and Siôn Jobbins is a good one.

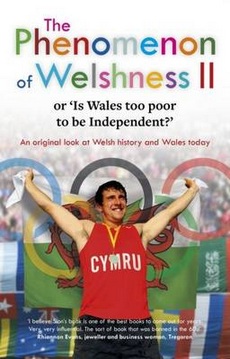

The Phenomenon of Welshness 2, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 263 pp