- Joao Morais travels to the SITE Festival 2012 to witness a performance exchange.

- It’s hard not to pay attention to Iwan ap Huw Morgan when he starts his performance. Wearing a full-face balaclava, he enters from the back of the Goods Shed, a Brunel-designed former railway depot in Stroud, ringing a bell and stomping around, making members of the audience get out of his way. It’s almost as if he is looking for something, but we don’t know what. It’s also obvious that he has great spatial awareness and has the ability to make the most of the building’s great acoustics. Catching everyone unaware that the performance is about to start, everyone feels disrupted and defensive. It’s a cracking entrance.

By taking off the balaclava and covering himself in chalk and ash, the artist completes his ritual transformation from the old to the new. Like the boys in Goulding’s Lord of the Flies hiding behind their painted faces, he is free to act as he wishes.

As the performance progresses, Morgan becomes more like a caged animal. It is common for animals in zoos to try and stimulate themselves by re-

The audience is left revelling in the ambiguity of the performance. Is this catharsis or a cry for help? By the end, the artist is a lot more subdued. In a highly intense cathartic moment, the artist purges all feeling and thought by putting all the surrounding artefacts in the middle of the room and sets them on fire.

But this wasn’t the only ritualised action of the night. Paul Hurley is a wiry, athletic man with the muscle definition of a welterweight boxer; if it wasn’t for the white y-

It was at about this time that I lost concentration in what was going on – not from the artist’s lack of skill, as I was curious as to what is going on and the show thus far had piqued my interest – but due to a disturbance from the audience itself. This show took place in the basement of a disused building around the corner from the Goods Shed, and on the other side of the room from where I stood was a small, young family. The two children in this family proceeded to start crying, to ask questions loudly, and to run or crawl into the artist’s space. Their father, much to the behest of the rest of the audience, refused to take them out. To be honest, I don’t know who was in charge of the room, but you would expect there to be someone on hand from the gallery’s administration to usher the crowd and make sure they behaved themselves. But there was no-

Eventually the children were taken upstairs, and the artist proceeded, in what seemed to be an extreme version of peacocking, to put on a leather jacket and put brightly coloured feathers on his head, using the paint as tar in a ritual transformation.

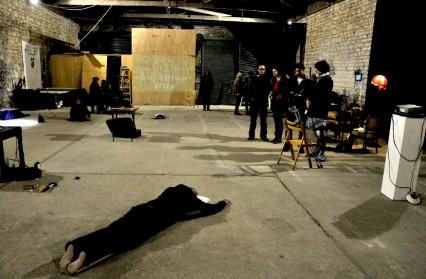

Phil Babot’s ‘Northerly planar conduction event’ couldn’t have been more different from Hurley’s physically demanding show, but was nonetheless equally as mentally demanding on the artist. Babot takes a methodical approach to craftsmanship. To start off he tacks a length of copper wire into a piece of wood, having first aligned everything with magnetic north.

An accomplished performer, he takes his time doing this – it doesn’t seem, as much performance art can, that he’s taking his time on purpose to accentuate the emphasis on what he’s doing. It is just a natural part of the performance and an extension of how he performs his art.

After setting an alarm clock, he lies down on the northernly-

With this being a ‘performance exchange,’ we can expect another show in this series on the Welsh side of the border before long; I, for one, am looking forward to it.

SITE Festival continues until May 31st