Gary Raymond looks at an unusual exhibition, in which David Hurn releases the favourite images from other photographers that he has collected during his sixty year career.

Vladimir Nabokov wrote in his lecture “Good Readers and Good Writers” that “we should always remember that a work of art is invariably the creation of a new world, so that the first thing we should do is to study that new world as closely as possible, approaching it as something brand new, having no obvious connections to the worlds we already know.” Swap: Photographs from the David Hurn Collection is an exercise in understanding how David Hurn reads, how he approaches new worlds and what he takes from them. The images on display, marking the opening of the Amgueddfa Cymru’s first exhibition space dedicated solely to photography, are the result of a lifelong love of the medium to which Hurn has dedicated himself since the mid-1950s. During this time he has engaged in the swapping of his own images for those of other artists he has crossed paths with. It is a charming idea that has resulted in a charming collection. On display are the images Hurn loves most, those that have, as it were, caught his eye during his career. But these are not just paragraphs in an essay on artistic influences, but an opportunity for Hurn to give up fragments of his own autobiography. We are, to an extent, getting a look behind the scenes.

Dorothea Lange’s importance hangs over Hurn as much as her words hang over this exhibition (“A camera is an instrument that teaches people to see without a camera” is stencilled high on the wall like a quote from the Bible). But lesser known artists are remembered here too, such as the late Tish Murtha, who Hurn taught on the now legendary Documentary Photography course Newport in the 1970s.

Hurn is a modest presence of gargantuan natural talent (he is famously self-taught), and it is surprisingly affecting, looking at some great images swapped for his own, seeing a hint of Hurn in them. In the photos donated to the exhibition, we see evidence of Hurn’s sense of humour, his love of life, his empathy. Although the exhibition may have a sense of humour it is not an in-joke. Many of these images augment an understanding of Hurn’s work, they bring addenda to his moments. Sebastiao Selgado’s de Mille-like “Workers” is so strikingly similar to Hurn’s Aberfan images that it almost serves to add a grim celestial coda to Hurn’s documentary work of the disaster. It has an eerier cinematic echo, and brings to mind cinematographers like Thomas Mauch, as well as the dark fiery nights of passages of Zola’s Germinal. Likewise, the David Seymour image of Toscanini bent over his piano with the death masks of Verdi and Wagner in a glass case behind him comes up on you as a bit of a surprise, and is wonderfully reminiscent of Hurn’s intense portraits of, in particular, Dora Holtzlander and Jacqueline du Pre.

The collection is, then, heavy with gems. It is like a cat burglar’s jewellery stash, you rummage through glistening precious stones of all shapes sizes, styles and intended appropriation, mirroring Hurn himself, as on point at a natural disaster as he was in Abbey Road Studios. And so Phillip Jones Griffiths’ Vietnam work is side-by-side here with Weegee’s Coney Island. And you have to remind yourself that all of these images were handed over in person as a mark of mutual respect and love. Cat burglar as Zelig.

To love this exhibition, however, is to pick out those precious stones. Altogether the layout is frustratingly overcrowded; it forces us to be overwhelmed, to flit our eyes from image to image, and you cannot help but feel this is how Hurn has gone about his life, that his work, his art, is what slows down this energy of attention. It is a fundamental law of curating that an image needs space in which to hang, to build relationships with the images accompanying it, and with the white space around it. The centrepiece here has none of that, and in general there are nearly twice as many photographs here as fits the room. The images need to breathe more, and all we get is this hyperventilating. The asphyxiating arrangement, like ancestral portraits of too-grand-a-lineage on an Edwardian drawing room, creates an uncomfortable Darwinian scramble for the viewer’s attention, and the losers come off as lacking character. Rebecca Norris-Webb’s inclusion for instance, may have much to say about the American landscape, about space and nature, but pushed up against Jérôme Sissini’s photographs of war-torn Aleppo her work looks like the storyboard for a Johnny Depp cologne commercial.

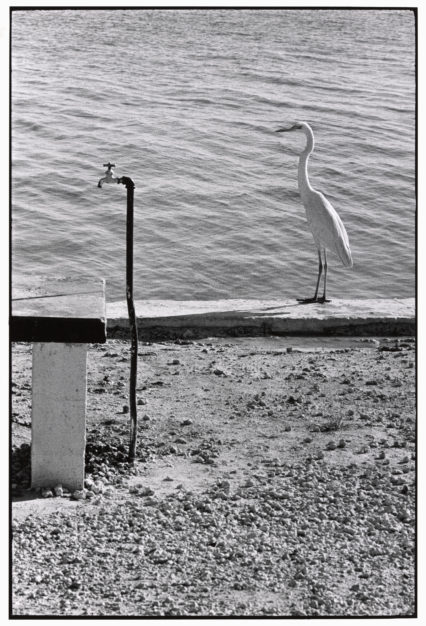

Before getting to this point, however, the curators have done a much better job of allocating space. Elliott Erwitt’s witty black and white is a perfect opener that feels very much to have a Hurnian sensibility. We are also introduced to the very personal nature of the collection. Martine Franck’s gift to Hurn hangs above her husband, Henri Cartier-Bresson’s, classic image of Matisse with uncaged doves out of focus in the foreground. It is pairings like this, these photographs full of depth of image but also reaching out to the world beyond the frozen moment, that you prepare the audience for a tour-de-force that unfortunately never quite materialises. Hurn’s work, at its very best, always seems to find symmetry in a frame, be it cacti lining a desert road, or the cut of Sean Connery’s sleeve, and it is perhaps the power of this neatness this collection lacks.

An exhibition of wondrous images, pulled together into a dissatisfying clamour.

This exhibition is on display at National Museum Cardiff until March 2018.

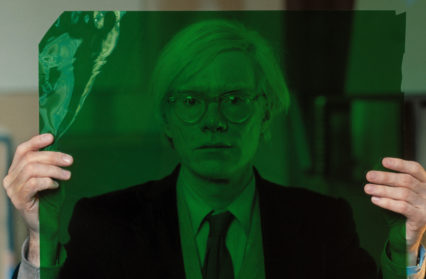

(Header image: USA. New York City, 1981. Andy Warhol in his “Factory” at Union Square © Thomas Hoepker/Magnum Photos) All images reproduced with kind permission.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.