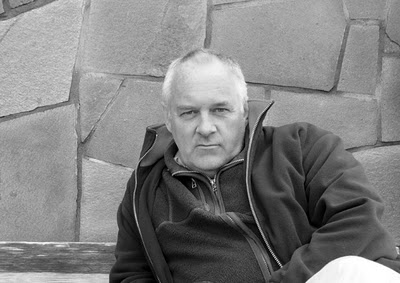

Padraig Rooney is an Irish poet now living in Switzerland. His latest collection of poems is The Fever Wards, published by Salt.

Carl Griffin: The mesmerizing title poem of your 2010 collection The Fever Wards deservedly won the Strokestown International Poetry Prize. What brought this poem about?

Padraig Rooney: An aunt who I never knew visited me in a dream. She had died in the Thirties from tuberculosis. My father brought me to see the old fever hospital in Monaghan, where I was raised, before it was pulled down some time in the Sixties. I remember a wrecking ball. But a late Fellini movie, and Tarkovsky’s movies, would also play a part in the poem’s narrative surrealism, where outside is simultaneously inside, and the past tucked inside the present. Cinematic images came together with dream memory, I suppose.

What themes have crept into your poetry since The Fever Wards collection?

My next book of poems will be called Dust Devils. It’s nearly finished. Many of the poems in it seem to be little leftover pieces of speech that I no longer hear, except in memory – fragments of people long dead, still haunting the soundscape. You get to an age where you know more people who are dead than are living. I got interested in poems whose idiom was part-Irish, part-something else. There’s a poem in it, ‘Conversations with the Dead’, which won the Listowel Award, and what I like about it is that ventriloquist quality. I don’t think these are new themes for me – are there new themes? – but maybe the old themes re-jigged and intensified. I got interested in short-line poems of two or three beats, as opposed to the longer narrative lines.

You’ve had three collections published in twenty-five years. Why do you like to take your time?

All the old enemies of promise clamour to be heard in response to a question like that. In my case, I haven’t had the pram in the hallway, but perhaps the schoolbag in the bedroom! I think I matured late as a poet. For a long time I painted and wrote prose, with not much to show for either. I’ve been abroad, mostly in Asia, all my adult life, and so there was not that connection with a publishing milieu, little magazines etc. There’s a half-baked idea in my head that the whole of English literature comes down to inclement weather and vicarages! It’s hard to work up drive in a tropical climate: it defeats you.

(For this month only) we know how you feel.

I was doing some research on Patricia Highsmith lately, in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern, where her papers are. I came across a copy of London Magazine in which there was a piece by Barbara Skelton on Highsmith. And then I noticed my own name on the cover – I’d had a story in it, but never actually saw the issue – until twenty years later. It’s no big deal. Poems come when they come. Different careers in poetry have different shapes, if we’re speaking of careers.

You had a poem published in The Captain’s Tower, a book of poems about Bob Dylan. Are you a big Dylan fan? What’s your favourite Dylan album/era et cetera?

I am a Dylan fan, without being too Nick Hornby-ish about it. I came of age with Blood on the Tracks, though I had been freewheeling long before that. There was a big day-glo poster of a mop-head Dylan on my bedroom wall, with stars coming out of his hair, and I had a harmonica rack. There are so few crossover lyricists and, at his best, Dylan is one of them.

Are there any good young Irish poets (or older Irish poets just starting out) you can introduce us to?

I can’t pretend to be that much in touch. All summer I’ve been reading Shelley and bits of Byron, for a piece on their time in Switzerland in 1816. I like the way Shelley’s ‘The Mask of Anarchy’ has found a new relevance. American poetry exerts its pull on me as well: David Ferry’s Bewilderment and D. A. Powell’s Useless Landscape are two voices I’ve liked from outside the mainstream.

Salt are abandoning single-author poetry books. How important have Salt been for the poetry world, and do you think other publishers will be forced to do the same over the next few years?

Salt has been a very dynamic presence in the poetry world. Their retrenchment is part of a wider taking stock in publishing. I’m not on the side of the death of the book – and can happily read on a range of media. We have a book week at the school where I teach. Despite iPads and Kindles, kids for the most part still pitch up with a paper book to read, rather than an electronic device. The mix of video, animation and poetry is exciting, and there’s some wonderful stuff on-line which makes poems sexier.