‘Revelation’ is the second story in our new Story: Retold series. It is a re-interpretation of the Rhys Davies short story of the same title.

Emma stops to watch, neck extended, eyes narrowed to paper cuts. The breath in her trachea is static as the man at the park entrance lifts the wad of mud to his mouth, a skinny pink worm tail hanging from its edge. He’s good-looking she can see, Arctic blue eyes, an elegant scattering of white in his dark hair. The muck coats his face as he chews, smearing up his cheeks, the worm tail vanished. The little blond boy beside him chuckles frantically. ‘Yummy,’ the man says to the boy. He opens his mouth and points at the sludge on his tongue. ‘Delicious,’ he says.

The dog scrapes his claw on the tarmac, impatient. ‘Floyd!’ Emma chides him absently. She winds the dog’s lead twice around her wrist. At the park entrance the good-looking man propels the mud pie towards his son. ‘You try some,’ he seems to say. He’s not speaking English as Emma had first assumed, instead it’s Slavic and glottal, Polish or Ukrainian. But happiness is distinct in any language she realises, their two faces gleaming fuchsia with jubilation. The dog jerks abruptly, the chain around Emma’s wrist tightening. ‘Floyd!’ she snaps, and she hears it in her voice, the swollen catch. She’s been crying, silently, for a minute, maybe longer; fat tears sprayed down the collar of her trench coat. She starts to walk, wiping her face with the cuff of her blouse. It’s mid evening, late September. The nights are drawing in. No one will notice, she thinks, as she rubs at her eyes, nobody looks at her anymore. Maybe the kids do but they’re at home guzzling full fat coke and tangy cheese Doritos, bullying one another on the internet.

Gradually she gets closer to the entrance and the good-looking man glances at Floyd without raising his head, quickly eyeballing the Setter’s forelegs. ‘He’s safe,’ Emma says, a kind of reflex. The man semi-smiles at Emma before going back to his work, drawing patterns on the mud pie’s surface with his fingertips. She can feel the sorrow now, physical, lodged in her throat, heavy and jagged as bedrock. She wants to respond to the man’s tepidity. ‘Listen you, I’m a chemistry teacher. And that boy shouldn’t be messing about in that dirt with his bare hands. Don’t you know the kind of bacteria that lives in dog faeces? And anyway he shouldn’t be out this time of night. Rain due at any minute and he’s not wearing a coat.’ He wouldn’t understand, she thinks, he’s foreign. Besides, she knows the child is cherished, that her tears are tears of resentment. The same prickle of irritability in the staffroom this morning when Hopkins the PE teacher’s son turned up demanding the lunch money he’d forgotten and instead of reprimanding him Hopkins reached up trying to ruffle the boy’s product-sticky ginger hair.

She needs to pee. As soon as she gets indoors she careers up the stairs to the bathroom, Floyd left circumnavigating the lounge, his lead dragging on the floorboards. It’s only when she’s sitting down, jeans pushed to her knees, that she realises the front door wasn’t locked. Beneath her elongated stream of urine she hears music, bold and up-tempo, coming from the basement kitchen. Her eyes cross as she concentrates on the lyrics, frisking the song for clues. You can burn my house, steal my car; drink my liquor from that old fruit jar. It’s been months since she’s heard music in her own home. Immediately it enlivens her, her heartbeat accelerating. She stands and wipes at herself. She darts down the stairs. By the time she gets to the kitchen the song has changed to ‘Jailhouse Rock’. Her husband’s at the island, squat and dirty blond. He’s singing the words, loudly and with an accent, drawling the awful chorus. He swings his hips right to left and then chops at an onion, slicing a few cellophane-thin slivers. He doesn’t see Emma there, facing him, the music’s volume blunting his senses. It’s a hell of a thing to watch a man in his dirt-encrusted boiler-suit overalls, dancing like nobody’s watching; the eight inch blade of a carving knife brandished in his hand.

‘Elvis?’ she asks him when the song ends.

Justin drops the knife on the wooden chopping board, metal clattering. He practically launches himself at the stereo on the shelf above the sink and turns the power off, the CD whirring to a standstill. ‘A hero to most,’ Emma says. A hollow sensation stuffs the cavities between her cells where the delight at hearing melody had so recently pounced. ‘You’re early?’ she asks him. Justin lifts the chopping board and pushes the onion slivers trickling into the pot on the stove. ‘Starving, I am,’ he says.

‘You didn’t have to knock it off,’ she tells him. She nods at the CD player. ‘It’s nice to hear you listening to music.’ He grunts in response and turns to stir the curry, his back to her. She takes his knife, starts halving a sweet pepper. ‘Did you know that Elvis’ bowels were backed up with twenty-eight lbs of excrement when he died? He hadn’t had a shit in four months.’ Toilet humour, she thinks, he’ll like that. But he throws a handful of diced chicken into the frying pan, the oil searing and spitting, the fledgling conversation expired.

After dinner they sit on separate settees, a news report on the television from East Jerusalem. Justin’s holding a large key, scrubbing at its layer of black grease with a clump of moistened toilet tissue, gingham tea towel draped over his lap. Steadily his wiping reveals a tarnished silver. ‘That’s a pretty one,’ Emma says as the news breaks for adverts, the flame of the Yankee candle reflected in the key’s elaborate throating. ‘Where did you get that one?’ She tries to sound interested, not scornful, but she hates it already. It’ll go in the trinket box on the bathroom windowsill with the hundred-and-fifty-odd others, dusty and useless. Why keys, she wants to know. So many keys. As if he’s locked out of somewhere he really needs to be. Most people collect cigarette lighters, rare coins. She collects key rings from away days at the seaside, but she’s only got one, from a hen weekend in Cornwall. Since she decided on the venture it’s the only place she’s been.

‘From the guttering,’ he says. ‘Job in Tonyrefail.’

Floyd drops his head on Emma’s chest with an exaggerated sigh. She scratches at his ears, his soft, red crimped hair between her fingers. ‘Why keys, Jus?’ she asks her husband. ‘I mean, most people collect rare coins, stamps.’ When he doesn’t respond she lifts her head to look at him. He’s fallen asleep, his mouth open as if to catch the raindrops just started outside, fist cuffed tight around the key shaft.

She hopes to hear music when she gets back from the park the following day. Instead there’s the vulgar squeal of the buzz saw. Her father-in-law is here, fixing the plinth under the dishwasher. Her mother-in-law is sitting in her spot on the settee, cardboard-coloured hair tightly-permed, arthritic hands swollen, dabbed at their extremities with lilac nail polish. Emma crouches to unfasten Floyd’s lead. ‘Gooboy,’ she says, holding the dog momentarily in a tight bear hug, delaying the inevitable dialogue with Justin’s mother.

‘If you liked babies as much as you did dogs I’d be a grandmother three times over,’ Judith says. ‘How’re things?’ Emma feels like one of those coin push machines at the amusement arcade in Barry Island, jammed up with other people’s expectations. Judith has flipped the last two penny piece that Emma can shoulder into her slot. Now she’s won the bonanza. ‘Things?’ Emma says. She throws herself into Justin’s corner on the opposite settee, arms folded. ‘You mean the state of my sexual relations with your son?’

‘No!’ Judith lurches backward as if she’s been slapped.

Over the din of the machinery below them Emma tries to repair the damage with her odd brand of shrivelled-dry humour. ‘I’d be lucky if he stayed awake long enough to get an erection.’ Judith lights up, red as a beef tomato. But it’s true. Justin’s always asleep, because Justin’s always tired, because Justin’s always working. When he’s not at his own work he’s helping his father out mending something or other. When Justin was growing up Justin’s father liked to think of himself as a man’s man. That meant spending the majority of his time with other men, exuding the masculine qualities of fixing houses or sinking pails of beer, sometimes both together, while all out ignoring the existence of his wife and children. From him Justin learned absence and repression. It’s a show of weakness to befriend the opposite sex or to acknowledge your own kids. ‘You want me to bear children that haven’t got a hope in hell’s chance of a daytrip to Caerphilly Castle?’ she thinks.

Judith rubs her hands together nervously, purple nail varnish stuttering between revolutions of sore and flushed skin. I should give her something to hold, Emma thinks, cold-eyeing her. I should offer her a cup of tea. But Judith doesn’t like tea made with bags and the teapot is cracked. ‘I’m going for a shower,’ she says and she stands and leaves the room. In the bathroom, hot water scalding her shoulder blades, she thinks about how she came to be in this position. There was no shortage of affectionate company in the beginning. They’d sit up on school nights drinking red wine, arguing about the merit of The Stone Roses. He’d done enough, just enough, to get her up the aisle and no more. Maybe children are doomed to repeat their parent’s mistakes. But if that were true she would have divorced him by now. Her mother, stubborn as a fact, didn’t bring her up to take this crap. The idea of a woman like Judith, waiting patiently at a warm oven while her husband’s holed up in his mate’s garage with a six pack of Hofmeister and a faulty clutch would be a pitiable joke to her mother, party-loving and hard-drinking. Emma’s trying. Justin should step forward and meet her at the halfway point. She whips the shower doors open with so much force one of them flies off the rail. A couple of hours later, mildly nauseas after a whole block of Dairy Milk, she’s sprawled in front of the TV when Justin appears having cleared up the sawdust his father’s left in the kitchen. ‘What’s this?’ he says at the sight of a tangerine-skinned woman in an epic white silk gown. ‘Big Fat Gypsy Weddings?’

As if she’d watch such a thing. ‘It’s a documentary about the Grand Canyon. It’s Vegas.’ The camera footage switches to queues of men dressed as Elvis Presley, Mexican and Chinese forty-something’s, satin jumpsuits peppered with rhinestones. ‘There’s an Elvis festival in Porthcawl, isn’t there?’ she says remembering this suddenly.

‘There’s rugby on S4C,’ Justin tells her. He lifts the remote and points it at the screen. Connaught are beating the Ospreys 21-9. ‘Bollocks,’ he spits. But there is an Elvis festival in Porthcawl every year, Emma thinks. They’d been on their way home from the builders merchants in Nottage last autumn, the backseat loaded with aggregate when an octogenarian had limped over the zebra crossing in front of them, outfit opened at the chest to reveal an ugly V of hoary chest hair. She remembered because Justin had grinned and grinning wasn’t Justin’s style. She hadn’t been sure what his expression was meant to signify.

At eight on Saturday morning Emma wakes, half blind with exhaustion after yesterday’s year nine field trip to Techniquest. Justin’s crouched at the end of the bed, searching in the murky light for clean underwear. He’s stepping into his spare pair of jade-coloured overalls when she resolves to resist the heady warmth of the duvet. She manages to sit up, her hair fallen down over her face. ‘What are you doing?’ she asks him, voice raspy. ‘You’re not working today, are you? I thought we’d go out.’

‘I promised my father I’d help him.’

‘Of course you did,’ she says. She wishes she still smoked. For the first time in three years she fancies a cigarette. Then she thinks of the photographs they started putting on the packaging when she’d stopped; the wrinkly pink baby, the oxygen tube in its teeny button nose. Justin turns the collar of his overall down. ‘He’s damp proofing Stimpy’s shed. We can do something tomorrow. Drive to the ice-cream van on the Bwlch after dinner?’

‘The weather’s bad tomorrow.’ She tries the word out in her head and then she says it aloud, ‘No.’ She brushes her hair out of her face. ‘Do Stimpy’s shed tomorrow. I want to go to Porthcawl.’

Justin looks at the floor. ‘We didn’t get as far as the doughnut stall last time. Come on, Em. You’re bound to see one of your pupils. You’ll hate it.’

‘Most couples go on holiday once a year, you know?’ she says. ‘Even your father takes your mother to McArthurGlen on August Bank Holiday.’

‘Well.’ He pulls at his earlobe. ‘I need a bag of Mastercrete to finish the wall off down the back. If we go the Brackla way we could call in Jewson’s.’

Emma springs out of bed and dances around him, heading towards her side of the wardrobe. She can feel him looking at her unusually naked thighs as she moves. ‘Yeah, if you don’t mind hardware shopping in this.’ She drops the costume onto the unmade bed, the sparkling red stars studding the legs, glowering through the plastic wrapping. She’s hired it for the weekend from Party Animals in Pontypridd.

‘What?’ he says. ‘What if someone sees me?’

‘Now who’s afraid of being seen? What d’you think? That your father’ll think you’re gay?’

Downstairs the postman stuffs something through the letterbox. Floyd whines with glee. ‘It’s just a couple of hours out of the house. I thought the costume would help. You know, get you into the spirit a bit.’ Justin sits down on the bed with sigh. After a moment he turns to regard the tacky outfit with a sullen air of curiosity. ‘I’ll do it if that’s what you want,’ he says, voice hushed as if their Anabolic steroid-addict neighbour might hear him through the wall.

‘I know,’ she says. He’d do anything she asked. He’d do anything his father asked. All she wants is for him to make a decision for himself.

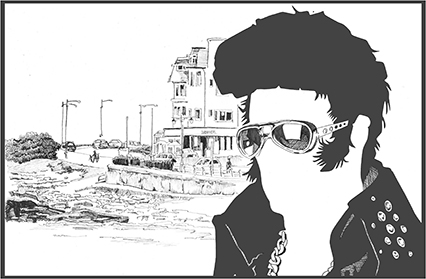

Coney Beach looks exposed, the weak midmorning sun emphasising the cracked art deco tiles of the first bar on the corner of the esplanade. Seagulls circle the dove grey sea, yawping their heads off, while joke shop Elvis’s puff on roll-ups in the doorway, skin like crepe paper. A young couple leaves the bar holding hands, three sheets to the wind, the girl with Amy Winehouse hair, uppercase letters tattooed above the boy’s knuckles. Two yards along they start arguing, hurling tremendous expletives at one another in Scouse accents. There is nothing more disappointing than a cliché that’s true, Emma thinks. ‘It’s murder on my nuts, this thing,’ Justin says scraping at the inner thigh of the costume. The flares don’t quite meet the tops of his old cowboy-style ankle boots as he tramps up the forecourt trying to avoid the little heaps of sand blown from the beach. ‘You look great,’ Emma tells him, teeth gritted.

Punters push in along the bar of the Hi-Tide like suckling piglets, a sickly-sweet odour trapped in the wainscoted walls, composed of sea salt and candyfloss, old smoke and Eternity perfume. Emma buys a pint of Heineken for Justin. They sit down in a recently vacated booth close to the door. ‘How’s school?’ he asks her after a few minutes of silence.

‘Even when you’re the teacher it’s like school.’

‘It’s funny how I ended up with a teacher,’ he tells her. ‘I hated every teacher I had when I was a kid.’ He expects her to laugh but she doesn’t. ‘I love you, like,’ he says sensing trouble.

‘You think you’ve ended up somewhere?’ She sips at her lemonade. ‘I don’t think it’s the end yet.’

‘You’re not drinking,’ he says studying her as she sets her glass down.

‘I’m driving,’ she says.

‘You can have one.’

This was a waste of time, she thinks. I could tell him to hike Pen y Fan barefoot and he’d do it. He’d be back down in two hours, changing into his work clothes and heading for the pit in his parent’s garage. He’ll kill himself trying to please everyone. ‘Fifty quid that costume cost me,’ she tells him.

‘You didn’t drink anything last night either,’ he says, eyebrows meeting in a scowl. ‘No wine on a Friday night? Or the Friday before that.’

‘I’m counting calories,’ she says. It’s the wrong answer. She ate his chicken Biryani, boiled rice and a whole Peshwari Naan to herself on Wednesday. He’s eyeing her suspiciously. She nods, encouraging him to believe her. She doesn’t want to tell him. Not yet. She hasn’t decided on anything yet.

After four pints he’s paralytic. He’s not used to alcohol. He’s usually too busy working. He keeps misjudging the space between the table’s surface and the base of his glass, the lager splattering. ‘When I’ve done that wall down the back I’ll refit the shower,’ he says with an obvious slur. ‘It’s leaking, isn’t it? I noticed when I reset the door. It’s leaking a little bit.’ Emma brings her finger to her lips. ‘Shut up about fixing things for a minute.’ He scans the room, bereft of a new topic, watery eyes wide. The karaoke competition is starting soon, the compere arranging the microphone on the stage. A small woman in a flared eighth note-print skirt is making her way around the room handing out songbooks, taking names. Emma lifts her hand to wave her away from the table but Justin reaches out to accept one. ‘What shall I do?’ he says flipping jokingly through the laminated flyleaves. ‘Wooden Heart? Shall I do Wooden Heart for you, babe?’

‘Don’t ask me,’ she says. ‘I hate Elvis.’

‘My mother loves Elvis. She used to make me dance with her to Elvis songs when my father was out late. She taught me the octopus, the Wurlitzer, the—’

‘She was lonely?’’ Emma asks him.

He looks up from the songbook. ‘Yeah, I suppose she was.’ He closes the cover and puts the book down on the table.

‘You wouldn’t confess to all these people here that you haven’t got a wooden heart,’ she says, glancing around at the crowd. Rugby boys in the recess with Mr. Greedy bellies, pint glasses perched at their lips. ‘You can’t tease me, Jus. You’re not your father, I’m not your mother. It’s not the seventies. I’m an intelligent woman. I can see through you like a window.’

The eighth-note woman is hovering at the next table along. ‘Wooden Heart,’ Justin says passing the songbook back to her. ‘You’re up first then,’ she tells him. She points at the stage, the compere in his blue teddy-boy suit and black quaffed wig, a roll up behind his ear.

‘No,’ Emma says, a forced smile on her lips. ‘He’s joking.’

He raises his hand now, waving at Emma. ‘Don’t speak for me,’ he seems to be trying to say. ‘Watch this,’ he tells them both. He twists in his chair and straightens up with a flourish. He follows eighth-note to the front of the crowd. Emma can see the slight grimace on his face as he steps onto the stage, the hem of the jumpsuit wedged between his buttocks. He takes the microphone out of the stand and flexes the cord. It loops perfectly, lasso-like. The barmaid cheers. ‘Thank you,’ Justin says in his ridiculous Southern American voice. The accordion starts. Emma falls back into her chair, hand pressing lightly on her tummy. The shock of this is going to send her into an early labour, she’s sure.

See Wales Arts Review this Sunday for a new interview with Rachel Trezise.

Original artwork by Dean Lewis.