Brady Knight is at the Newport Art Gallery to review the final exhibition in their Temporary Exhibition Programme, Shift by David Garner, an exploration of Welsh history heavily focused on the tragedy of Aberfan.

David Garner is at once both a political activist, and an artist. If one word can be used to describe the subject of his work, the theme of his artistic position, it would be ‘malaise’. He is concerned with the state of affairs of the most afflicted peoples of a society (which isn’t necessarily the minority), and provides a voice, a harrowing cry out, for their rights and dignity. It is a poignant and sentimental arrangement of works that make up his show Shift in the Newport Art Gallery, Temporary Exhibition Programme, a programme that is to be discontinued in the very near future, Garner being the final artist to show there. This story is all too familiar in the city of Newport, with shops shutting down left and right, consistent deterioration make it hard for any economy to thrive there, least of all that of art culture. So, pertinently, and with a greater sense of sorrow, this show also stands as a kind of memorial, an epitaph, for the current state of the affairs in the art culture of Newport, South Wales today.

We start with history, as is appropriate; all affairs of modern culture begin with the affairs of less modern culture. We enter David Garner’s exhibition, surrounded by the white walls synonymous with all contemporary art galleries, but are challenged by the historical artefacts we find therein. A cross-section of history in Wales, the exhibition showcases artefacts from the last century, intuitively manipulated or arranged in a melancholy statement using Garner’s sentimental symbolism.

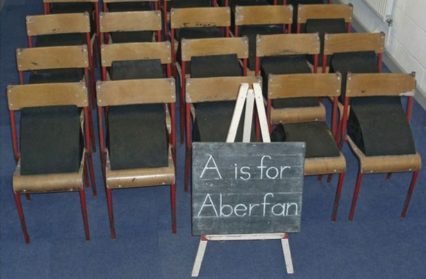

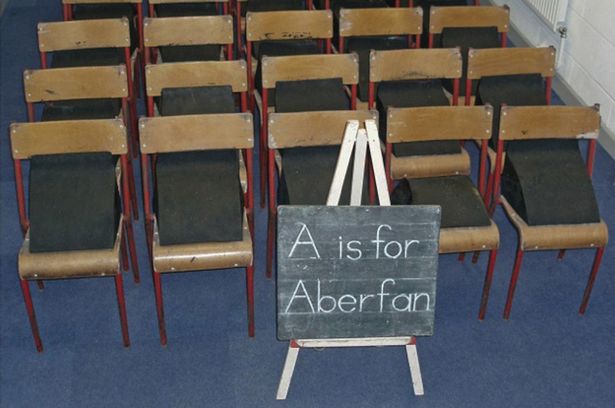

Central and most prominent piece of the show, we have the haunting ‘A is for Aberfan’, a grid arrangement of old wooden school chairs, worn and faded over time, tightly grouped together to resemble a classroom from a more draconian era. We see the classroom laid bare, fronted by an old chalkboard with ‘A is for Aberfan’ neatly inscribed, an odd abacus at the back with mittens instead of beads for counters, but what is haunting about the work is the distinct lack of child presence. An echoing, almost obnoxious silence unexpected from a classroom, however draconian, emanates from the work, and we are aware of the absence of children. This aspect of the piece is no accident; Garner creates his ode to the Aberfan mudslide tragedy in 1966, where an avalanche of thousands of tonnes of coal and slurry from a mining tip crushed a small junior school, killing 116 children and 28 adults. We begin to identify the significance of the finer details of the piece in this light; the odd mittens on the abacus, stained with tar, symbolise the loss, not just of loved-ones, but emotionally and culturally too. A writing desk inscribed ‘21/10/66’ marks the date of the event like a tombstone, opened upright, mirroring the blackboard heading the class, a lesson in history and culture, as an entire generation is lost.

‘A is for Aberfan’ establishes a poignant sentiment and a cultural theme for the show and as we move on we maintain our appreciation of the tragedy and view the rest of the works in its light. Circling around the central Aberfan piece in a kind of abstract narrative, the other works lead us on a journey through other aspects of the era of equal cultural affliction. Unusual, abstractly symbolic arrangements of artefacts describe the way of life for people in 1940s-1970s Wales; as if we are witnesses to a crime, we see how our parents, grandparents and great grandparents were forced to live.

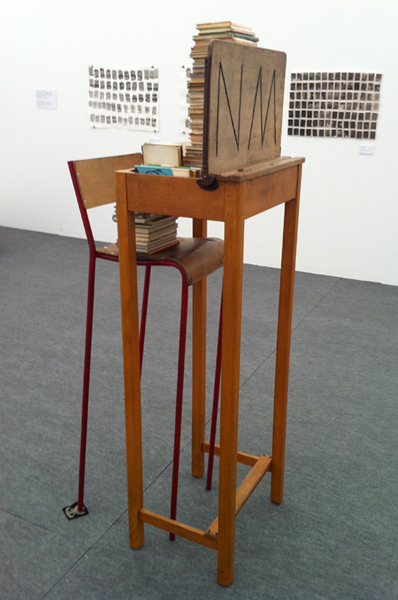

We start the journey, appropriately, as they did – at school. A tall, tentatively stacked tower of books on a tall desk makes up the piece ‘All the books I could have read, but were out of reach’, a commentary on the impaired and prescribed education assigned to many children then, given few or no opportunities other than a career in mining. We move around to the start of employment, a factory locker, to store belongings whilst on your long shift, solitary and solemn, a poignant relic. On to working conditions: a recreation of miners’ barracks comprised of different equipment; an old stretcher makes up the bed, balanced on two coal pails, a trail of ash leads from the door to the bed, as relieving as a miner’s rest must be, he can’t leave his work far behind him.

A chest X-ray next, dressed in a miner’s coat, an oxygen mask leading from the mouth down into a pail of coal, a haunting death certificate attached to the back – ‘Cause of death: Chronic obstructive airways disease’. A more disturbing piece, titled ‘Do Not Go Gentle’, insensitively informs us of the miners’ horrid health conditions. And finally at the head of the exhibition, an antique clocking-in machine, appropriately beginning and ending the cycle of artworks. Another poignant relic, each clocking-in card wryly inscribed ‘A. Workman’.

We see the life of the miner, harrowing yet unheard; working in unimaginably poor conditions, today it would be considered a cruel and unusual punishment. But we also see their categorised lifecycle, pigeon-holed indiscriminately by their origins and class, ‘A. Workman’ slotted into the uniform clocking-in slots of the ancient clocking-in machine. They do not learn, or rather are not taught the luxury of choice. Institutional oppression lies subtly amongst the details and undertones of David Garner’s work and he draws such a striking picture of the era and the afflictions of its denizens, spurred on initially by the tragic impact of ‘A is for Aberfan’, as to be loosely comparable to such a national, cultural disaster and breach of human rights as perhaps the holocaust, or the onset of slavery. Harrowingly affecting whilst mesmerizingly intelligent.

The theme of malaise features strongly in much of Garner’s work and it is often heralded as a hugely potent political statement for both historical and modern concerns. With Shift, a unique and powerful opportunity of context arose with the current deteriorating state of art culture in Newport, headed by the closure of the Exhibition Programme.

A series of cutbacks are the reason behind Newport City Council’s decision to close the Temporary Exhibition Programme. Several spokespeople have stated that permanent collections in the gallery will continue to run, but other temporary exhibitions in the city are now proposed to run in the Riverfront. The councils failure to discuss the issue with arts professionals in the city before making the decision so alternative courses of action could be considered, have created further furore over the decision.

So Garner’s exhibition becomes a subversive comment on the similarities in cultural deprivation of the mining era in Wales and Newport’s current art scene, and central in a very heated debate over the city’s future. One state of malaise shifts into another, where we see citizens de-individuated and categorised by class, people and culture are both deprived as one neglects the other through oppressive economic priority, the same happens here where funding cuts hinder the already dwindling art culture of Newport and we are forced to watch it shrink ever further.

After learning of the planned closure of the Exhibition Programme, Garner produced a new work, ‘A Case of the Great Money Trick’, which features in Shift. Pinned upright underneath a height measuring stick from schools of the mining era is a book – the seminal working-class novel The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists. Youthful motivation possesses such strong potential – the ragged-trousered philanthropists, but are restricted and moulded into functional working-class citizens by educational institutes of the time. Garner symbolically expresses the minimal worth attributed to culture and education of the era, but subversively reflects the similarly minimal worth attributed to culture here in Newport as decisions such as the closure of the Exhibition Programme are made.

We are shown the direct impact of cultural indifference, beginning from a safer distance in Shift where we learn of history and past events, but moving into personal territory when we see the closure of the successful and pivotal art venue in Newport where the show is housed; the white walls of the contemporary art gallery fall down around us. Malaise; a state of wrongness; in David Garner’s work a state of cultural affliction. Executed expertly with David Garner’s affective symbolism, Shift is a powerful and provocative show, but also a poignant end of an era with a hugely influential cultural significance.

Recommended for you:

Siân Gwenllian argues that Wales’s arts sector is not being looked after in its time of direst need with many programmes suffering from underfunding, and that the future of its very existence is hanging by a thread.