Dora Stoutzker Hall, Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama, Cardiff, 16 March 2017

Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 in D, Op.25 (the ‘Classical’)

Michael Nyman: Where The Bee Dances

Mozart: Symphony No.39 in E flat, K543

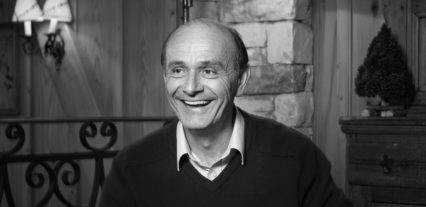

Conductor: Gábor Takács-Nagy

Jess Gillam (soprano saxophone)

Not the least advantage of having saxophonist Jess Gillam reach the finals of the BBC Young Musician contest in 2016 was the opportunity to hear an unfamiliar musical instrument in obscure parts of the repertory. Almost completely appropriated by jazz as though jazz might have been awaiting its invention, the sax has also had a presence in dance bands concerned with strict tempo sounds. They have a job to do; instrumental solos are non-flashy so as not to draw attention to themselves or interrupt the swirl on the dance floor. Gillam herself is well aware of her instrument’s magnetic links to the local palais and to jazz, and she often incorporates jazz or its derivatives in her concerts. But it was her breezy personality that helped her shoulder her way to the front in a contest dominated by instruments graded in terms of their popularity among listeners. Since its inception in 1978, the competition’s winning-instrument tally has been violin (five), piano (four), cello (three), trombone and clarinet (two each), horn, oboe, and percussion (one each). There are sound reasons for that, but also objections to its bias on the grounds that one should only compare like with like. One problem for anyone outside this consensus is the lack of music with which audiences can identify, and it’s clear that including transcriptions of scores written for other instruments is best avoided. Audiences can be fickle and unadventurous.

Gillam, still just eighteen and returning to the very building where she’d won through to the competition finals, was the perfect guest for Sinfonia Cymru, an orchestra defined by its youthful zest and ambition. She bounced onto the platform like a musical emissary from the constellation of Aquarius, wearing a sequinned jacket, skinny tux trousers and shining boots. In her hands, evoking some talisman incapable of being wrested from her, was the soprano saxophone, possibly the one member of the sax family least likely to ripen her audience’s latent prejudice. And for the soloist slot she settled on the piece she performed in the BBC Young Musician final, held at the Barbican in London: Michael Nyman’s Where The Bee Dances, written for her teacher, John Harle. While the title diverts from any expectation that it might be a one-movement concerto in the commonly understood sense, it soon transfers its thrust to the ensemble and away from the exposed soloist. Although it goes through some interesting rhythmic and minimalist-style developments, it too early morphs into a contest from which the soloist can do nothing to take shelter – that’s if she wants to – despite the impression given that a return to its reflective opening with the orchestra’s pianist Gamal Khamis might have been welcome, not to say appropriate. But its formal progress brooks no circularity and it riffs ahead at high pitch and volume.

That said, it’s a vibrant and virile piece, though maybe not one in which the contest’s participants can show what each is made of in terms of one being given time and space to josh with and impress the other. (Might its gregariousness have edged her off the winner’s rostrum last year? We shall never know.) Perhaps it all accounted for Gillam’s encore, Pequeña Czarda, by Pedro Itturalde, originally scored for alto sax and piano but here played as a stand-alone on the soprano. It was as if the orchestra had left the race exhausted. Gillam, as ever, was all smiles. Nyman’s piece did elicit uninhibited, not to say clamorous, playing from all concerned via the promptings of guest conductor Gábor Takács-Nagy, musical director of the Manchester Camerata and much else. He was all smiles too and, after Gillam’s party piece, borrowed orchestra violinist Thomas Aldren’s instrument to perform with leader Caroline Pether in Bartok’s pizzicato Duo for Two Violins No 43. Just for the hell of it.

In fact, Takács-Nagy was in zippy form all night. With his announcements, brief snippets about the music, impromptu turn, and encouragement aimed at the audience’s maximum enjoyment, he might have been presiding over a programme that in its pulsation had been made to integrate via some intent aforethought, yet with an appearance of being extemporised. His interpretations were always entertaining and often quirky, particularly when his deliberately variable tempi and wide dynamic intervals allowed us to hear goings-on within the orchestra that might otherwise and in different hands have been glossed over. This was certainly true of Prokofiev’s ‘Classical’ Symphony, whose unevenness in our more generous moments we might have been inclined to call originality of shape. But there’s no need to match Prokofiev’s wit with humour of one’s own. If it was too heavily accented in a way that had little to do with its marriage of old and new, it at least signalled how the evening was to pan out.

Takács-Nagy was quick to alert us to the operatic character of Mozart’s Symphony No 39 and perhaps too quick to apply to it what he thought was right for the Prokofiev work. But, my, did he perform the essential task of getting the orchestra to ‘sing’ and by implication to render the symphony as a swan song in all but its forward-looking momentum. There was again the advantage of close focus, as in the second subject of the first movement’s allegro, shared by violins and woodwind with accompanying cellos – what some have described as its ‘Zerlina’ charm. There was contrast in the second movement, its return to the first theme performed with clarity of counterpoint, and a playful sense of release in the final movement. But the apotheosis of the conductor’s spirit on the night was in the third movement’s minuet, almost a separate and vigorous invitation to the dance, in response to which the idealised trio was mere diversion, a glance through the ballroom window. As an orchestra encore he reprised it, perhaps over-insisting on the invite. One can praise the orchestra no more highly than to say it responded obediently and with enthusiasm to what this conductor asked of it, even when it was not what it might have expected. We all learn and live.

Touring to Newport (March 18), and Mold (March 19): http://sinfoniacymru.co.uk/event/gabor-takacs-nagy-jess-gillam/

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.