These last two weeks have seen the passing of two giants of improvisational music, but also two musicians and composers who brought their own spheres into the Western popular mainstream, influencing Anglo-American pop and, in turn, the tastes of the record-buying public.

Ravi Shankar, who has died at the age of 92, became known as the ‘Godfather of World Music’. Dave Brubeck, who was 89 when he passed away last week, and was up until recently still touring, changed the fundamental mainstream view of jazz in 1959 when he released his album Time Out; the record that came from it, ‘Take Five’, is still the biggest selling jazz 7-inch of all time.

Both men introduced a wide, wealthy audience-in-waiting to riches that may otherwise have gone ignored; Brubeck through his accessible, riff-driven smooth sound, and Shankar through his friendship with the Beatles, and most importantly, George Harrison.

Ravi Shankar, the pre-eminent sitar player in Indian music at the time, used the enthusiasm of the Beatles in 1966 to deliver his country’s music to teenager’s bedrooms across the world, with Harrison in particular sticking his Indian rhythms onto Beatles pop albums. Harrison looked up to Shankar as a guru, in matters spiritual as well as musical (although for both of them music and the spirit were inseparable). Harrison never again strayed from the ethos instilled in him by Shankar, and some of his most musically successful solo recordings are infused with his influence.

Notably, it can be seen in the establishment of the Harrison-led Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden in 1971. The first event of its type anywhere in the world, Harrison pulled together a star-studded list of musicians, (which included getting Eric Clapton off heroin and Bob Dylan out of retirement), to perform a fund-raiser and awareness-raiser for the famine taking place in Bangladesh. Shankar, the principal mover and the man who introduced Harrison to the plight of the Bangladeshis in the first place, opened the show with a 16-minute sitar improvisation. The stunning virtuoso set piece takes up the entire first side of the Grammy Award-winning live album that followed. The New York audience, excited by the prospect of Dylan’s re-emergence and the possibility of Clapton soloing on ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’, are palpably held in thrall to the pure vision of the sound heavily hinted at in Harrison Beatles tracks such as ‘Within You, Without You’ and ‘Love You To’. Shankar, a superstar in India, (and famous in classical circles through the championing by luminaries such as Yehudi Menuhin), had little trouble in globalising his talent and, significantly, his seemingly serene and amiable personality. It is difficult to imagine the sound of the late Beatles period without the influence of Shankar, and it follows that the sound of the entire psychedelic and ‘flower power’ era would have been quite different without Harrison’s introduction of the sitar to pop music. What the Concert for Bangladesh did was present, at the top of the bill, the genius of the man who had brought it thus far.

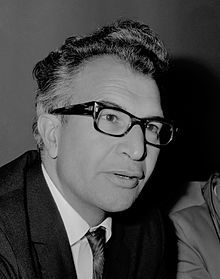

Ravi Shankar at Concert for Bangladesh, 1971

Shankar’s music though, in reality, had its closest cousins in the jazz halls of America and the gloriously grimy pockets of Europe where black American musicians often migrated for seasons to get paid what American promoters refused to pay them: their worth. Miles Davis found that not only was he treated with respect and adoration in Paris (where Shankar himself had studied) in 1949, but that he was paid good money to play and nobody spat at him if he took a white girl to a party. The connection between Shankar’s understanding of improvisational music and that of the American jazz musicians is clearly heard on the opening set of Concert for Bangladesh. (Shankar was understandably flattered by the attention of the biggest superstars on the planet in the Beatles, but pop music must have seemed slightly trivial in the wake of Bitches Brew and In a Silent Way).

The respect and understanding was reciprocated. Davis’ greatest protégé, saxophonist and composer John Coltrane, named his son Ravi in honour of the sitar player over a year before the Beatles had even met Shankar. It could perhaps be taken a little further if we explore Shankar’s experiences (albeit as the son of a successful barrister) growing up under the Raj, and Davis’ frequent persecution and humiliation at the hands of bigoted white Americans.

Dave Brubeck, in the 1950s, was at the receiving end of the other side of that ugliness. Brubeck was heavily criticised for ‘anglicising’ black music, for taking the soul of black America in the form of its music and presenting it to the middle-class, bohemian sitting rooms of white America. He was accused not only of cynicism and exploitation, but openly of racism. That Brubeck was a man of music down to the core of his soul, as far from a racist as you could find, and whose only interest was in playing the music that he loved, was of little interest to his critics. It is true that Brubeck often had an all-white band, but it must also be said that his best line-up, the quartet that played on Time Out in 1959, saw Eugene Wright take up bass. Perhaps the real gripe with Brubeck’s brand of catchy jazz was that his frat boy looks made huge swathes of white Americans comfortable buying ‘black music’, and so he sold in huge numbers and became a star, whilst the true geniuses were either dying in drug-soaked squalor by that time, or were still fighting battles they found themselves in simply because of the colour of their skin. But to those who knew him, Brubeck was a gentleman, an inclusive, who just went about his business as a jobbing musician and took everything in his stride.

The music was the thing; and perhaps those who only know him for ‘Take Five’ (which is not actually a Brubeck composition, but that of his supremely talented and equally spiky saxophonist Paul Desmond) would be surprised at just how interesting his compositions could be. On Time Out, as an example, Brubeck displays his genius for incorporating African scales and Bosphorus-singed syncopations into what end up as extremely palatable western jazz riffs. ‘Blue Rondo a la Turk’ is perhaps his most successful composition. You can always spot a Brubeck track, regardless of where it comes from in his mind, and that was perhaps one of his greatest gifts; his style.

‘Blue Rondo a la Turk’ by The Dave Brubeck Quartet

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.