The literature of the American South has produced some of the most influential writers of any single concentrated geographical area. There is a style, a swagger to the books of the south that make the canon a particular treasure trove of old and modern classic. Here Wales Arts Review’s top writers search for their personal favourites in the heat and the dust.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) by Maya Angelou

Felicity Evans

Maya Angelou’s voice, like her writing, was deep and strong and warm. Yet for years as a child she chose not to use it. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is the story of how she lost her voice and how she found it again. And in the telling of that story, her life from the age of three when she and her brother moved to live with her grandmother in Stamps, Arkansas to sixteen when she held her own baby son in her arms, she presents us with a rich metaphor for the experience of African American people living and dying in the violent apartheid of the American South.

Maya Angelou’s voice, like her writing, was deep and strong and warm. Yet for years as a child she chose not to use it. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is the story of how she lost her voice and how she found it again. And in the telling of that story, her life from the age of three when she and her brother moved to live with her grandmother in Stamps, Arkansas to sixteen when she held her own baby son in her arms, she presents us with a rich metaphor for the experience of African American people living and dying in the violent apartheid of the American South.

Maya learns the importance of language early on, when she becomes convinced that her own words have killed her rapist – found dead shortly after the court case in which he was prosecuted. For an insecure little girl, reeling from motherly rejection and the relentless daily poison of pervasive racism it could have been the last straw. Maya could so easily have become the real life Pecola in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, the story of a little black girl, convinced of her ugliness, driven to madness and self-hatred by racism and sexual violence.

But Maya has much love in her life too, the devotion of her brother and the kindness and sternness of her grandmother – the moral centre of her story. The dignified and educated black woman Bertha Flowers cultivates a love of literature in her and encourages her first attempts at poetry. It is Ms Flowers who breaks though her silence: I will no longer read your poetry, she tells Maya, poetry is meant to be spoken out loud. If you speak, I will listen.

‘There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you,’ Maya writes. And what a storyteller she is. This book is literate, funny, anger making and full of pride in a people who would never be ground down.

Maya Angelou was encouraged to write this book by her friend, James Baldwin, whose own tales of northern American racism are an eloquent counterpoint to Maya’s own story of the south. Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell it On the Mountain, is autobiographical. Angelou’s autobiography is novelistic. Both explore the ways that bigotry perverts a child’s developing sense of self.

But ultimately this book is about triumph. The pain is not irrelevant, it still matters but it will not define her. By fifteen Maya is already the first black streetcar conductor in San Francisco. By sixteen, with a child of her own, she has not simply found her voice; she also knows what it is for. It’s for using. And she will use it to change the world.

The Moviegoer (1962) by Walker Percy

James Lloyd

I remember listening to a radio interview with Joyce Carol Oates in which she was asked about what advice she would give aspiring writers. Oates said something like, whatever gets your heart beating when you are reading a book, read around it. I supposed then that Oates was talking about building a personal literature map, one that demonstrated an aspiring writer’s own personal affectations, a guide that would go on to inform their own writing.

I remember listening to a radio interview with Joyce Carol Oates in which she was asked about what advice she would give aspiring writers. Oates said something like, whatever gets your heart beating when you are reading a book, read around it. I supposed then that Oates was talking about building a personal literature map, one that demonstrated an aspiring writer’s own personal affectations, a guide that would go on to inform their own writing.

This was in my early twenties when I was particularly impressionable and had already gone through Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller and Paul Auster phases. Without knowing it I had, of course, been developing my own literature map, but my choices had not yet formed a country I could call my literary home. It was on discovering the work of Richard Ford that my literature map started to form something like a country, an archipelago more like, but it was through this great writer that I discovered three of my favourite novels: A Sport and a Pastime by James Salter, A Fan’s Notes by Frederick Exley and The Moviegoer by Walker Percy.

It is Percy‘s The Moviegoer that has perhaps continued to resonate with me most strongly. Having read it again before the writing of this short piece, it is an elegant novel, pregnant with wit and wisdom. But most of all it is a call-to-arms in the fight against the spiritual disintegration of the age, one that has resulted in people living adrift in a kind of domesticated despair. The latter is a reference to Flannery O’Connor’s wonderful quote: ‘At its best our age is an age of searchers and discoverers, and at its worst, an age that has domesticated despair and learned to live with it happily.’

Throughout the early stages of the novel there are flashbacks into the past as well as Binx’s digressions on his relationships with various secretaries and God. These are significant because they hint at his sense of isolation and his rather vague, perhaps idiosyncratic, impulse to embark on a search:

What is the nature of this search? you ask.

Really it is very simple, at least for a fellow like me, so simple that it is easily overlooked. The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life […] To become aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be on to something is to be in despair.

At the beginning of The Moviegoer is an epigram taken from Søren Kierkegaard’s, The Sickness Unto Death: ‘…the specific character of despair is precisely this: it is unaware of being despair’. In spite of Binx’s clear longing to attach some meaning to his life, a yearning for something, that is, without being able to define exactly what it is characterises it, he doesn’t admit to his despair. When Binx’s aunt, the formidable Emily, compares him to his father (‘he had a mind like steel trap, an analytical mind like yours’), Binx replies, ‘I have never analysed anything.’ Binx isolates himself and yet wants to belong. His reflections on the past and meditations on various subjects allows the reader to tease out his loneliness.

The Flannery O’Connor quote, whether informed by her reading of The Moviegoer or not (it appeared in Mystery and Manners in 1969, whereas The Moviegoer was published in 1961), sums up well the contradictions that form part of the Binx’s vision of the world. His ‘peaceful existence in Gentilly’ is complicated by ‘the idea of a search’, but also enlivened by it. He rallies against the enemy that is ‘everydayness’ and also takes ‘pleasure in doing all that is expected’ of him:

My wallet is full of identity cards, library cards, credit cards. Last year I purchased a flat olive-drab strongbox, very smooth and heavily built with double walls for fire protection, in which I placed my birth certificate, college diploma, honorable discharge, G. I. insurance, a few stock certificates, and my inheritance: a deed to ten acres of a defunct duck club down in St Bernard Parish…

Driven by the belief in and possibility of redemption, by the end of the book the spiritual urgency that initiates Binx’s search has become something nobler. Valuing the memory of his wounding in the Korean War, when he hovered on the edge of consciousness and unconsciousness, being and nothingness, Binx is determined to use the experience to communicate the truth of our relationship to the world and our being.

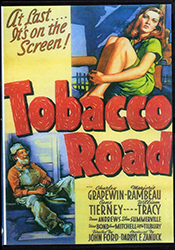

Tobacco Road (1932) by Erskine Caldwell

Rachel Trezise

Erskine Caldwell’s 1932 novel Tobacco Road is probably the most affecting work of literature I have read, Southern or no, and like Saul Bellow, I tend to think Caldwell should have won the Nobel for it. Set in a fictionalised adaptation of Caldwell’s home town, the novel tells the story of the Lester’s, the whitest and poorest sharecropping family in rural Georgia, exploited to the point of starvation by rich loan companies and banks. The opening scene, a master class in opening scenes, introduces us to an entire family, acting in complete desperation, working to steal a sack of winter turnips, purchased by their friend and visitor, Lov Bensey, who is so sickened by their behaviour he very quickly leaves. While Jeeter and his wife Ada, preoccupied with their certain and imminent deaths, search for ways to avoid being buried in old and unfashionable clothes, or having their bodies stored in the coal shed where they will be nibbled by rats, the children, eighteen-year-old, Ellie May, voluptuous and hair-lipped, (it is classically Southern with too many grotesqueries to mention here) and sixteen-year-old Dude go about trying to get out, Ellie May by way of seducing turnip-owner, Lov, and Dude by marrying a lecherous thirty-nine-year-old female preacher, though mainly that’s because he wants to drive and honk the horn on her new Ford.

Erskine Caldwell’s 1932 novel Tobacco Road is probably the most affecting work of literature I have read, Southern or no, and like Saul Bellow, I tend to think Caldwell should have won the Nobel for it. Set in a fictionalised adaptation of Caldwell’s home town, the novel tells the story of the Lester’s, the whitest and poorest sharecropping family in rural Georgia, exploited to the point of starvation by rich loan companies and banks. The opening scene, a master class in opening scenes, introduces us to an entire family, acting in complete desperation, working to steal a sack of winter turnips, purchased by their friend and visitor, Lov Bensey, who is so sickened by their behaviour he very quickly leaves. While Jeeter and his wife Ada, preoccupied with their certain and imminent deaths, search for ways to avoid being buried in old and unfashionable clothes, or having their bodies stored in the coal shed where they will be nibbled by rats, the children, eighteen-year-old, Ellie May, voluptuous and hair-lipped, (it is classically Southern with too many grotesqueries to mention here) and sixteen-year-old Dude go about trying to get out, Ellie May by way of seducing turnip-owner, Lov, and Dude by marrying a lecherous thirty-nine-year-old female preacher, though mainly that’s because he wants to drive and honk the horn on her new Ford.

The book works like an early prototype for a Channel 4 reality series about benefit recipients; you can’t stop turning the pages because you want to see how much lower your jaw can drop, but the terror and obscenities that arise come from Caldwell’s sincere attempts to illustrate his political sympathies for the struggling farmers he knew growing up, and to portray what happens to a good person when they are forced into a corner. Sometimes the writing veers from hard naturalism and realistic dialogue to sheer poetry. One character says: ‘Once the sun was so hot a bird came down and walked beside me in my shadows.’ And of course it is as relevant now as it is ever been. I can see the characters in the novel right now, through the window overlooking my street. Heck, I have even got a nineteen-year-old cousin called Ellie May.

A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) by Tennessee Williams

Jane Oriel

How I love Tennessee Williams! Over time, his characters have assisted me in party night plans, aspirations and melodramatic conceits. Who shall I be tonight? Maggie the Cat. Shall I channel her cunning charisma to rise above Big Daddy’s mendacious madhouse characters? She has the control. Just ask Brick, who wears the pants in her house. Or maybe this evening’s abiding call is for the aloof, insularity of Laura Wingfield, living in a world of her own, ‘a world of little glass ornaments’. But for a palette of traits that draw both pity and boredom, curiosity and ridicule, desire and repulsion, the epitome of enigma to both herself and others, please extend a welcome to Blanche Du Bois, the fascinating, compelling but unwitting Azazel from A Streetcar Named Desire.

How I love Tennessee Williams! Over time, his characters have assisted me in party night plans, aspirations and melodramatic conceits. Who shall I be tonight? Maggie the Cat. Shall I channel her cunning charisma to rise above Big Daddy’s mendacious madhouse characters? She has the control. Just ask Brick, who wears the pants in her house. Or maybe this evening’s abiding call is for the aloof, insularity of Laura Wingfield, living in a world of her own, ‘a world of little glass ornaments’. But for a palette of traits that draw both pity and boredom, curiosity and ridicule, desire and repulsion, the epitome of enigma to both herself and others, please extend a welcome to Blanche Du Bois, the fascinating, compelling but unwitting Azazel from A Streetcar Named Desire.

Masked, I advance.

So, who do I want tonight? Marlon Brando looks like everything Williams wanted in his Stanley Kowalski, husband to Stella, the sister of the evocative Blanche. The mind’s-eye lust that drops to the page finely detailing what he, the playwright, desired, makes me agree.

Animal joy in his being is implicit in all his movements and attitudes. Since earliest manhood the center of his life has been pleasure with women, the giving and taking of it, not with weak indulgence, dependency, but with the power and pride of a richly feathered male bird among hens. Branching out from this complete and satisfying center are all the auxiliary channels of his life, such as his heartiness with men, his appreciation of rough humor, his love of good drink and food and games, his car, his radio, everything that is his, that bears his emblem of the gaudy seed-bearer. He sizes women up at a glance, with sexual classifications, crude images flashing into his mind, determining the way he smiles at them.

The gaudy seed-bearer. Oh, my…

Convinced that Blanche has swindled Stella of her inheritance, each fur, each expensive gown and refined glove serve to antagonise the man. With Stella as pivot between Stanley and Blanche, the husband and sister dance the dance of barely concealed, mutual disdain but from when he overhears Blanche dismiss him as a survivor of the stone age, who will either ‘strike, or maybe grunt and kiss you, if kisses have been discovered yet’, he is out to teach her a lesson, to put her in her place. This revenge compulsion strengthens on its inevitable course, to finally ignite once he learns that her pure white, virginal composure is at odds with the grubby truth, thus dissolving any rights she might have had to salvation.

Oh! So you want some rough house! All right, let’s have some rough house!

[He springs toward her, overturning the table. She cries out and strikes at him with the (smashed) bottle top but he catches her wrist.]

Tiger tiger! Drop the bottle top! Drop it! We’ve had this date with each other from the beginning!

[She moans. The bottle top falls. She sinks to her knees. He picks up her inert figure and carries her to the bed.]

Blanche was on the wrong side of the age old, virgin/whore dichotomy. The big guy sorted her out. She had it coming, didn’t she? He’s the man and she needs to remember it. That kind of woman, she deserv…… She what? What exactly happened there?

STANLEY! RAPED! BLANCHE!

While enjoying this classic work once more after a gap of twenty years, I didn’t expect to be faced by my historic misogyny. Stanley takes her to the bed with anger, much as Rhett forcefully carries his wife Scarlett, another Southern Belle, up the huge staircase in Gone With The Wind, with similar intent. A subject too broad for the scope of this analysis, the stereotype of presumed awkward, overgrown, child-like women, is, however, connected to my earlier complicity (and dare I say, thrill) at their punishment on film. As though I were a passenger on the infamous Delhi bus in December 2012, I previously had either ignored or tacitly processed Blanche Du Bois’ humbling as something that just ‘happens’ to problematic women.

At the end of the play, Stella agonises over committing her sister to an asylum, but settles herself with ‘I couldn’t believe her story and go on living with Stanley’. Still reeling at my former negligence, a change in attitude is vital, and in the wider world too as the recent London hosted Global Summit to End Sexual Violence Against Women shows. What started for me as a romping re-visit, concludes as a creature of a different shape. Yet as a finely honed study of gender micro-politics, A Streetcar Named Desire remains a work of genius.

As I Lay Dying (1930) by William Faulkner

Peter Gaskell

I came to William Faulkner via Ken Kesey whose Sometimes a Great Notion so impressed me for the prodigious energy and freshness of its narrative. Admitting the influence of Faulkner, Kesey wrote his book from the points of view of different characters as had Faulkner in As I Lay Dying, but using no chapters.

I came to William Faulkner via Ken Kesey whose Sometimes a Great Notion so impressed me for the prodigious energy and freshness of its narrative. Admitting the influence of Faulkner, Kesey wrote his book from the points of view of different characters as had Faulkner in As I Lay Dying, but using no chapters.

As the perspective moves seamlessly from one character to another in first person, sometimes in third or using italics, this can prove unsettling at first, but Kesey gets his technique working well in revealing the motives of characters unable to communicate well with each other. While Faulkner wrote chapters titled with the narrator’s name, it took some time before the identities of his characters and their relationships became clear to me. Certainly As I Lay Dying is a book you have to read more than once to appreciate the subtlety of how events narrated from differing perspectives are interwoven with the plot’s development.

Assessing who might have influenced Faulkner in writing As I Lay Dying, James Joyce in his use of stream of consciousness and metaphysical speculation, is the prime candidate. The only chapter narrated by Addie Bundren (she who lay dying), about love and marriage, is clearly reminiscent of Molly Bloom’s monologue at the end of Ulysses (episode Penelope) leading up to her response to being wooed by her husband Leopold. And Addie Bundren’s view about language:

Words are just a shape to fill a lack. Words are gaps in peoples’ lacks. Sin and love and fear are just words that people who have never sinned or loved or feared have for what they never had and cannot have until they forget the words.

This suggests the albeit more self-consciously intellectual ‘Thought is the thought of thought’ with its Aristotelian reference by Stephen Dedalus in Ulysses (episode Nestor) as he struggles to discover his identity.

Faulkner’s inventiveness with his language can bewilder the reader, also like Joyce.

Suggesting two meanings of the word ‘spring’, the Budrens’s neighbour Vernon Tull appears to envy their fertility despite their family discord as he and his wife Cora have no children.

The more the sweat, the tighter the house because it would take a tight house for Cora, to hold Cora like a jar of milk in the spring: you’ve got to have a tight jar or you’ll need a powerful spring, so if you have a big spring, why then you have the incentive to have tight, wellmade jars, because it is your milk, sour or not, because you would rather have milk that will sour than have milk that won’t, because you are a man.

As well as evocative imagery like ‘bone-gaunted’ mules, Darl is the one to use original vocabulary e.g ‘re-accruent’, ‘suspicioned’, ‘ludicrosities’, ‘pussel-gutted’ and ‘uninferant’ as in his fascination with the passage of time: ‘We go on, with a motion so soporific, so dreamlike as to be uninferant of progress, as though time and not space were decreasing between us and it.’

As I Lay Dying you could describe as Ulysses written in the vernacular of the American South.

If anyone needs further inducement to read Faulkner, I would refer them to what Ken Kesey had to say:

You can go back to any piece of Faulkner and open it up and begin to read it, and it works. You don’t know where it comes about in his scheme of things; you’ll see one story done by him at one time, and then the same story done by him at another time, where he is looking from a different point of view, getting a different look at stuff. This is my favorite writer, by far.

This story itself told from multiple perspectives, As I Lay Dying is a good place to start.

Men We Reaped (2013) by Jesmyn Ward

Jim Morphy

To make choosing a whole lot easier, instead of going for an all-time number one, I will pick my favourite Southern book of the year so far. Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped is a beautiful and tough memoir of growing up in rural Mississippi. In four years, Ward lost five men close to her to drugs, accidents or suicides. To tell their stories, Ward finds herself telling her own story as well as that of her community.

To make choosing a whole lot easier, instead of going for an all-time number one, I will pick my favourite Southern book of the year so far. Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped is a beautiful and tough memoir of growing up in rural Mississippi. In four years, Ward lost five men close to her to drugs, accidents or suicides. To tell their stories, Ward finds herself telling her own story as well as that of her community.

Writing in The Guardian, Gary Younge said: ‘Melancholic and introspective rather than morbid and self-indulgent, it is really a story of what it is like to grow up smart, poor, black and female in America’s deep south.’

Men We Reaped is raw and heartbreaking, but, thanks to its writing, it is entirely graceful too.

Men We Reaped does in memoir form what Ward’s superb Salvage The Bones does in fiction (her memoir shows much was based on experience). Salvage The Bones follows its young narrator and her family in the days leading up to Hurricane Katrina hitting Mississippi. Mother Nature is just one of the many problems – others include alcoholism, violence, poverty and unplanned pregnancy – facing the family. However brutal it is at times, Salvage The Bones is shot through with an essential belief in humankind. It’s life-affirming stuff.

Men We Reaped and Salvage The Bones are both very much of their place. Their Southern locations are full characters in their stories. Both books are real, here and now.

‘Life in the Iron-Mills’ (1861) by Rebecca Harding Davis

Gary Raymond

Now, here is a peculiar literary work: clearly one of the most powerful and profound works of social writing ever published, a work that foreshadowed American realism, a masterpiece of form, craft and voice, that is almost entirely forgotten outside of scholarly circles. ‘Life in the Iron Mills’ is a harrowing tale, startlingly modern in its execution – the unnamed narrator spends most of the story with his/her face pressed right up against the reader’s. Here laid bare is the small change of Big Business’ exploitation of migrant workers in American factories in the 1900s; every sentence is saturated with inhumanity, made all the more wet for its coating in the language and imagery of the King James Bible. Harding, a middle class Pennsylvanian, was moved to write the story that made her name when her family moved to Alabama, and this, contextually, is the story of an outsider looking in – but in the South Harding found the story of a nation – no, not of a nation and not of an era, but of the fat viscous underbelly of capitalism. It is an indictment of everything capitalism is, and all it can be.

Now, here is a peculiar literary work: clearly one of the most powerful and profound works of social writing ever published, a work that foreshadowed American realism, a masterpiece of form, craft and voice, that is almost entirely forgotten outside of scholarly circles. ‘Life in the Iron Mills’ is a harrowing tale, startlingly modern in its execution – the unnamed narrator spends most of the story with his/her face pressed right up against the reader’s. Here laid bare is the small change of Big Business’ exploitation of migrant workers in American factories in the 1900s; every sentence is saturated with inhumanity, made all the more wet for its coating in the language and imagery of the King James Bible. Harding, a middle class Pennsylvanian, was moved to write the story that made her name when her family moved to Alabama, and this, contextually, is the story of an outsider looking in – but in the South Harding found the story of a nation – no, not of a nation and not of an era, but of the fat viscous underbelly of capitalism. It is an indictment of everything capitalism is, and all it can be.

It is a seminal text in the evolution of what was to become known as ‘American Proletarian Literature’, and is a proud grandmother to epochal left wing masterpieces by the likes of Frank Norris and in particular Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906), about the Chicagoan union movements of the early twentieth century. But it is also difficult to imagine that Emile Zola did not take many lessons from Harding when writing his Rougon-Macquart novels, and Germinal (1885) above all.

Although Zola’s masterpiece outstrips Harding’s by a few hundred thousand words, they are resolutely linked through tone and compassion. Both have the anchor of the middle-class protagonist, and both dig deeply into the despair of the working class experience. Likewise the novella has been compared often to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, that it does in literary terms for the plight of the exploited migrants what Beecher Stowe did for slavery. But Harding, tellingly, had nowhere near the impact of either Stowe or Zola (who, at his funeral in 1902, would have seen a procession of 50,000 French miners chanting the name of his novel, ‘Germinal! Germinal!’).

Rather, Harding made a good living as a hack writer in the years following her praise for this her first published work (in The Atlantic magazine), and published over 500 pieces of fiction and journalism during her lifetime. She did not publish anything quite so strikingly powerful as ‘Life in the Iron-Mills’ ever again, although from the 1970s on she was rediscovered as a writer of proto-feminist works. But for most who come across her work today, it is the power of her compassion that is irresistible and the thing that moves most keenly. The prose is unrelenting, and there are few examples of such sustained oppression in the page as in Harding’s direct, knife-wielding prose:-

A cloudy day: do you know what that is in a town of iron-works? The sky sank down before the dawn, muddy, flat, immovable. The air is thick, clammy with the breath of crowded human beings.

And to top it all off, Harding makes Welsh her protagonist and his family:

The old man, like many of the puddlers and feeders of the mills, was Welsh, – had spent half of his life in the Cornish tin mines. You may pick the Welsh emigrants, Cornish miners, out of the throng passing by the windows, any day. They are a trifle more filth; their muscles are not so bawny; they stoop more. When they are drunk, they neither yell nor shout, nor stagger, but skulk along like beaten hounds. A pure, unmixed blood, I fancy: shows itself in the slight angular bodies and sharply-cut facial lines.

‘Life in the Iron-Mills’ is a simply stunning piece of writing, made all the richer for its cause – the humanity of all people.

original illustration by Dean Lewis