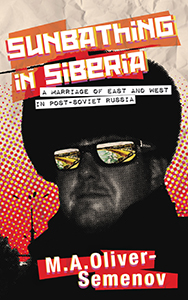

Parthian, 250pp

When invited to perform his poetry at a bilingual event, Michael Oliver’s sister comments that his ability to speak Welsh is on a par with his Russian. Amused, the poet decides that his next performance will be delivered in Russian and so he goes online to find a translator. His sister’s throw-away comment changes his life and leads to the chain of events that sees Oliver become Oliver-Semenov, and a fully stamped-up Siberian resident all within three years. Sunbathing in Siberia is his account of how this happened, who he meets and what he learns along the way; from his initial expectations of a frozen urban wasteland to the titular summer sunbathing.

When invited to perform his poetry at a bilingual event, Michael Oliver’s sister comments that his ability to speak Welsh is on a par with his Russian. Amused, the poet decides that his next performance will be delivered in Russian and so he goes online to find a translator. His sister’s throw-away comment changes his life and leads to the chain of events that sees Oliver become Oliver-Semenov, and a fully stamped-up Siberian resident all within three years. Sunbathing in Siberia is his account of how this happened, who he meets and what he learns along the way; from his initial expectations of a frozen urban wasteland to the titular summer sunbathing.

At the heart of this memoir is the love story of Oliver-Semenov and Nastya, the online translator he finds, falls for and marries. Their relationship is illogical, impractical and doomed by geography, economics and bureaucracy to fail. However love, as it will, finds a way to conquer all. Theirs is a sweet story and although it is the driver of Oliver-Semenov’s recollections, it is a story upon which hangs an array of other love stories: that of the love that grows between him and his new Siberian family; the love for what eventually becomes his new home; and the love that all of this inspires for the family and homeland he leaves behind.

Aside from the author and Nastya, distance and perspective are the main characters here, and what they bring about is a series of reflections that are at once beautifully insightful and challenging, yet at times shallow and frustrating. As Oliver (as he is then) meets his new wife’s family, his impressions of Boris, his father-in-law-to-be, are loaded with respect and love. Despite being terrifyingly macho, skilled with knives and guns and not averse to weeks on end in the forest hunting alone, a picture is formed of a humble but powerful man who does anything he can for his family and friends. Boris, like everyone and everything else new in the author’s life, is treated in his prose with respect and care rather than the distrust and patronising curiosity that is sometimes held for ‘the new’.

Descriptions of his Siberian family inevitably bring about comparisons to his own family in Wales and these are some of the most touching parts of the book. With only a small apartment for the whole family, Oliver-Semenov’s new in-laws sleep in the living room. This brings to mind his own parents sleeping in the living room as he grew up, and in his recollection, his awareness of the sacrifices made in his name heighten his appreciation for them. He writes a particularly touching memory of returning from a school trip as a child, and draws romantic links between Wales and Siberia and the similar hardships and love that tie the two families. Similarly, his heightened appreciation for the welfare state that once helped sustain his family gives him a poignant view of then and now. He writes that, ‘…seeing something as essential as the NHS being sold off bit by bit hurts even more, watching from a distance.’

While Oliver-Semenov’s handling of the personal and emotional is refreshingly open and insightful, the political and societal differences he describes between the East and the West tend to lean more towards the shallow and frustrating. A great example being his take on the arrest of all-girl punk band Pussy Riot in 2012 for playing anti-Putin songs in a church, making international news along the way. While still in support of the band, he expresses frustrations at what he perceives as the oversimplification of the case in the western media, and the painting of the protest as anti-Putin. Witnessing all of this from within Russia, his argument leans more sympathetically to the perspective that it was their anti-religious behaviour that got them arrested and not the anti-Putin tone of their performance. He fights oversimplification with his own oversimplification, which seemingly disregards the question of freedom of speech, despite at one point writing about it being unsafe to discuss it openly in Russia.

There are times, however, when oversimplification and his relatively superficial treatment of the injustices of society do work to effect. His reflections of the treatment of homosexuality and the backwards views he encounters are little more than frustrations. He has no answers and no alternatives, and so his description of a problem with no obvious solution only goes to highlight the size of the issue.

While there are tensions in this book between the varying depths and detail with which the personal politics are handled, what is consistent, however, is the portrait of a man in love. Sunbathing in Siberia is a great love story and shows what can be dealt with and what is possible with the right person at your side. Everything good that happens does so because of the kindness and love of others; this reflection applies to both his life in Cardiff and in Siberia. As he writes early in the book, people are people, wherever they are.