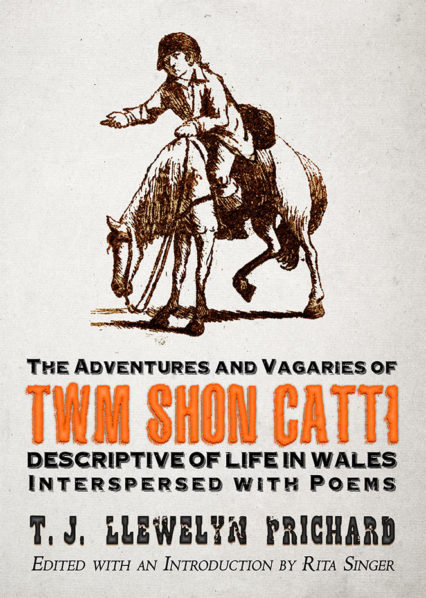

Bethan Jenkins takes a look at a new edition of T.J Llewelyn Prichard’s 1828 welsh folklore novel about Twm Shon Catti.

This new edition of T.J. Llewelyn Prichard’s 1828 work brings back into print one of the earliest Anglophone Welsh novels, a picaresque romp based around the life and legends of Tregaron’s quasi-mythical Twm Siôn Catti. Prichard assembled this patchwork quilt of a novel out of scraps and fragments of tales which agglomerated around the historical Thomas Jones of the sixteenth century, an antiquarian, genealogist and poet whose name and reputation over the years came to be intermixed with various highwaymen in the locality, and came to be marketed to the English-speaking world as the ‘Welsh Robin Hood’.

Prichard’s concern in his novel was to rescue Twm’s reputation from such reductive comparisons and present him as a character in his own right, whilst also presenting a vision of ‘Merrie Wales’ full of folk traditions, ballads, and colourful characters such as Wat the mole-catcher and Squire Graspacre. Prichard’s immediate stimulus was Welsh outrage at the appearance on the London stage of ‘Twm John Catti’ as a ‘Welsh Rob Roy’, whereupon he sought to reassert what he claimed to be the truth of Twm’s life and adventures, authentically Welsh and without reliance on comparisons with the heroes of Scotland and England. The result is a remarkable piece of work, not quite a novel, not quite historical fiction, woven through with ballads, songs, and poems in Welsh and English, and featuring imagined versions of genuine Welsh historical figures, as well as the sort of stock characters and situations which would not have been out of place in an anterliwt.

Rita Singer restores the original lively text of the novel, eschewing Prichard’s later, more ‘polite’ (and therefore more heavily self-censored) version of 1839. This gives us instead of a book that has a far more chaotic narrative, to be sure, not so much bound by what we would now recognise as the standard novelistic sense of order and progression, but much fresher and more immediate for this. Singer’s preface makes clear that what the second edition may have gained in polish, it lost in joie de vivre. Her preface also sheds light on Prichard’s own equally picaresque and disorderly life between London and Wales, publication and destitution (and the small matter of losing his nose in a duel), and his eventual death in the sort of grinding poverty of which we get glimpses in Twm Shon Catti. Drawing on Sam Adams’s previous biography as well as her own research, this is an excellent introduction to one of the liminal characters in Anglophone Welsh writing, whose life and works deserve to be more widely known. She also contextualises the novel for the reader perhaps unfamiliar with the age, providing useful insight into the genesis of Prichard’s writing, his readership, and the folkloric and social themes treated in the novel.

Prichard gives the reader Twm’s life story from before he was born, with no less a personage than Sir John Wynne of Gwydir fathering him after a dalliance with a peasant girl whilst visiting his brother-in-law, Squire Graspacre. Although Prichard calls ‘the sequel of the adventure’ ‘notorious’, there is surprisingly little censure of this illegitimacy, nor of that of any of the other children conceived out of wedlock in the novel, including Twm’s own. Indeed, the practice of ‘bundling’ or ‘courting in bed’ is seen as conducive to producing happy marriages and contented families, and Mrs Graspacre’s vehement objections to this tradition are presented to the reader quite clearly as an alien attempt to destroy local tradition and to be condemned as such, Prichard ‘rejecting the application of English middle-class mores to Welsh rural communities. The squire himself learns not to hold on to his ‘exalted opinion of English superiority generally’ following the failure of his ‘improving’ agricultural methods compared with the local customs and becomes an enthusiastic supporter of local dress and traditions. Our hero grows from an impish child to a roguish youth, albeit one who has the good fortune to be tutored by Sion Dafydd Rhys, from whom he learns an appreciation for learning and antiquities, ballad singing and poetry, and grows into a roguish hero:

Behold him now then in the seventeenth year of his age, with the looks and habits of twenty, gay, happy and as mischievous as an ape; kissing and romping with the girls, caring for none of them but shewing attentions to all, while he jeered and mocked the cross-grained and disagreeable, and whenever he could, raised a laugh at their peculiarities.

Twm’s adventures are mostly focussed on his ‘jests and freaks’ where he outwits pompous local authority figures such as Parson Evans or the Squire, though we also get darker tragic episodes, such as his time being cruelly abused as a hired hand at Cwm du farm.

This latter episode is truly shocking and gives a hint of the grinding poverty which must be prevalent throughout the communities of which Prichard writes, as well as the bleaker side of human nature which is not too far behind some of the jests and tricks which are the common currency of the local milieu — Wat the Mole Catcher’s eventual fall from grace is another such instance of the paper-thin distance between tragedy and comedy in this book. The dizzying speed in which these dark moments give way to farcical set-pieces such as the episode where Twm gets the better of the lecherous squire, now a widower, by bringing him farmer Cadwgan’s ass instead of Cadwgan’s lass, can give the reader a feeling as of literary whiplash. Turned out into the wide world following this ‘freak’, Twm affects various disguises during a whole slew of adventures — being attacked by footpads and getting his revenge in return, taking and winning bets with the local landowners, meeting the famous Ficer Prichard, saving a noble lady and eventually winning her hand. Throughout it all, Twm always seeks to defend the weak against the powerful and rich — indeed, the only real instance of Twm’s general good luck deserting him comes when he forgets the precept “War, not with the Weak”.

The book’s style is very much of the period, appearing somewhat antiquated, and may not suit some modern tastes. Prichard frequently uses what M. Wynn Thomas called ‘the pedantic footnotes of an autodidact’ to back up his claims to historical accuracy, and to explain to the reader the various Welsh traditions and customs which are woven through the novel as an integral part of its fabric — Twm’s antiquarian interests are in many ways a mirror of the author’s.

Though the story is set in the sixteenth century, this barely registers and the whole atmosphere of the novel’s setting and characterisation feels thoroughly eighteenth century, revelling in grotesques and eccentricities; and those of us who grew up with T. Llew Jones’s Twm Siôn Cati novels will find very little recognisable in Prichard’s hotch-potch of antiquarian sources, folk tales, ballads and pennillion. The novel’s moral compass may also raise some eyebrows now, as Twm too gets away with several rather dubious escapades where the reader might be disappointed by their expected narrative retribution, in particular his treatment of Gwennie Cadwgan. It certainly reads less like a novel than the series of stitched-together tales it surely is, taken by Prichard from the various tales and chapbooks of Twm’s legend.

For all this, though, it deserves to be read not just as a historical curio, or even as an important point in the development of Anglophone Welsh literature, but for the sheer fun of it. Reading these adventures brings to mind both Fielding’s earlier The History of Tom Jones but also the 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon, whose protagonist too climbs the social ladder by trickery and, ultimately, marriage to a rich widow (though without Twm’s happy ending). As squire Prothero remarks after being the butt of one of Twm’s freaks, “the fun of the thing repays the loss”, and the fun of this book surely repays the reader’s patience with its stylistic anomalies.

In Ystrad Fȋn a doleful sound

Pervades the hollow hills around;

The very stones with terror melt,

Such fear of Twm Shôn Catti’s felt.

This book is available now from Celtic Studies Publications.

Bethan Jenkins wrote an article on another Celtic Studies Publication, Rob the Red-Hand.