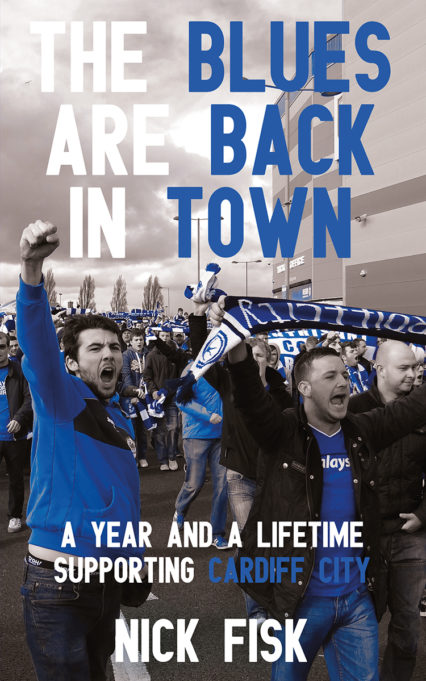

The Blues Are Back In Town by Nick Fisk: A Year and a Lifetime Supporting Cardiff City is reviewed by Bill Rees.

To grossly paraphrase Montesquieu, I am necessarily a man while I am a supporter of a football club by chance. Do we really choose the teams we end up supporting? Fate and our environment seem to do that, often in the guise of respecting family traditions. But Nick Fisk may be the exception, ignoring the memory of his first match (Swansea v. Spurs) and resolutely choosing Ninian Park over Vetch Field. Both of these grounds are now defunct, which can’t be said of the fanaticism of certain hard-core footy supporters. But such fans, laments Fisk, are becoming an endangered species. The Blues are Back in Town is a book that emphasises these points.

Once fans are smitten, it is for life. The club – in its essence – commands their unwavering loyalty. But what is the club exactly; its history, its supporters, its legal owner(s), the colours of the team’s home kit? These are the sorts of questions that Fisk raises in what is an agreeably opinionated fan’s diary of the 2014/2015 season following Cardiff City, or the Bluebirds as they are known. Interspersed are reports of matches deemed especially memorable, sections on supporting Wales (home and abroad) and various incidents (tangential to football) including the bizarre business of Ian Brown donning Fisk’s own Cardiff shirt at a Stone Roses concert in Newport. A riot thereafter ensued!

Once fans are smitten, it is for life. The club – in its essence – commands their unwavering loyalty. But what is the club exactly; its history, its supporters, its legal owner(s), the colours of the team’s home kit? These are the sorts of questions that Fisk raises in what is an agreeably opinionated fan’s diary of the 2014/2015 season following Cardiff City, or the Bluebirds as they are known. Interspersed are reports of matches deemed especially memorable, sections on supporting Wales (home and abroad) and various incidents (tangential to football) including the bizarre business of Ian Brown donning Fisk’s own Cardiff shirt at a Stone Roses concert in Newport. A riot thereafter ensued!

Fisk writes candidly on crowd trouble and pre and post-match boozing. And to my mind, he expresses a healthy scepticism towards the family orientated, corporate brand of football that many owners would like to impose at their clubs. (I’d be surprised to learn that the club shop stocks Fisk’s book.) Fisk is firmly of the old school, preferring to stand on a terrace as a spectator; hence his appreciation of Griffin Park, Brentford’s ground. He unashamedly links the culture of football to the pint, the bookies, and the invention of witty chants. A favourite being ‘Who let the goals in? – Jones, Jones, Jones, Jones, Jones!’ sung to the tune of ‘Who let the dogs out,’ a big hit in 2000 when Cardiff knocked four goals past Torquay. No prizes for guessing the name of their keeper.

Fisk draws a nice contrast between Sam Hammam and Cardiff City’s current owner, Vincent Tan. Hammam seems to have innately understood, and related to, the dreams and ambitions/delusions of Cardiff fans. They adored his maverick approach, which even involved courting some of the club’s hooligans by arranging free transport for a game. However, Hammam left the club’s finances in a parlous state. In stepped Tan who brought money (much of his own) and relative fiscal stability to the club, while wishing to rebrand it and change the home colours to red. Altering the traditional colours of a club is bound to play havoc with its identity. And as fans often merge their personal identity with that of their club, Tan’s decision was always going to prove controversial.

Fisk charitably outlines Tan’s argument (red having natural associations with Wales, etc.) but he remains scathing in his criticism of the move. As a Chelsea supporter (better to confess late than never), who imbibed at a tender age the notion that ‘blue is the colour, football is the game,’ I can easily imagine the ignominy of having your club turn out in red for home games. Fisk points out the absurdity of such a kit change (especially when the club continue to be referred to as the Bluebirds), detailing the various forms of protests, some personal like the farcical removal of red items from his house, and some public such as the supporters all holding up blue scarves 19 minutes and 27 seconds into a Championship game. A quick google will reveal to non-football fans why this time is very significant.

Eventually, in January 2015, Tan relented (his Buddhist mother apparently influencing his decision) and the team reverted to playing in blue. Unfortunately the resultant jubilation and energising euphoria was short lived, lasting just one match against Fulham. The trouble being that the atmosphere at Cardiff’s new stadium fails to match that of Ninian Park with fans only vociferous when winning. Fisk resents a new (and moneyed) breed of season ticket holder whose attendance at home games is perversely sporadic. They are a far cry from the sort who made the trip to Cold Blow Lane in 2011 to watch Cardiff draw 3-3 against Millwall. Part of this chapter reminded me of a John King’s The Football Factory; beer in Bermondsey bought with counterfeit money, the threat of violence outside the ground. Throughout, Fisk honestly hints at the dark glamour of football hooliganism, thrilled by the edgy atmosphere of rival fans in close proximity. In his musings upon Cardiff’s notorious ‘Soul Crew,’ he does not shy away from the idea, utterly alien to a tabloids’ mind set, that hooligan fans are just that – both hooligans and fans; some being of the most loyal variety.

Predictably there is a fanzine tone to the writing and Hornbyesque obsessiveness abounds. Disappointment and disbelief is expressed in equal measure over the form of players or the tactics employed by the manager. Solskjaer was sacked as Cardiff’s manager just ten games into a season which turned out to be a rather dull affair, although Fisk acknowledges that the Norwegian’s replacement, Slade ‘had steadied the ship.’

Some of the prose is repetitive, but that is the nature of match reports. And Cardiff FC, owing to their mediocre season, must shoulder some of the blame. Being a footy addict, I didn’t mind. Nor did I object to learning about Bluebirds’ arcana; the names of various sections of the stadium (stands being something of a misnomer) and their likely occupants’ predisposition to singing, fighting, etc.

What you get here are the trials and tribulations of being a football fan, but Fisk also manages to convey something that is perhaps more important. That following a football team is a means of meeting all manner of characters and making good friends. A lengthy list of people thanked on the acknowledgements’ page is eloquent testimony to this fact. There is also a confessional and touching piece on Dannie Abse, the poet and novelist, who, I was intrigued to learn, was a genuine Cardiff City fanatic. The book ends on an optimistic note, Wales’ victory over Belgium in a Euro qualifying game. Let’s hope there are many such victories over the coming weeks.

Bill Rees, author of Loneliness of the Long Distance Book Runner (Parthian) and Rebel Land: A Portrait of the Cevennes. (White Heron Press)