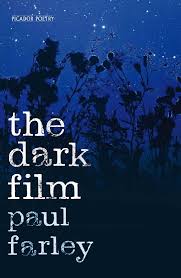

Carl Griffin reviews The Dark Film, Paul Farley’s latest poetry collection, a nostalgic and eclectic take on childhood experiences.

Paul Farley’s last collection, Tramp in Flames, started off with an impressive strong poem, with quality and authority shining through, and The Dark Film attempts that same brawny opening. The Liverpudlian’s tactic of including the reader in such an open manner, though, leaves the poem, ‘The Power’, a sitting duck for criticism. After instructing the reader to ‘Picture a seaside town/in your head’ he ploughs on with a clever, penetrative description of the seaside town before apparently praising the reader’s imagination, an acknowledgement that only a writer and reader combined make up a poem, by saying ‘Now look around your tiny room/and tell me that you haven’t got the power’. Or could it be less of an acknowledgement to the reader and more of the poet taking a bow: You didn’t know you had imagination until I came along?

It isn’t a lengthy delay before Farley throws solid weight with the punch. He employs teleportation himself to travel back in time and imagine himself a boy again. In ‘Adults’, he is the kid always watching, or stumbling upon, an indecipherable reality which ‘didn’t tally at all with my view of their world.’ And in ‘Force Field’, he sniffs himself back to the classroom, entertainingly executing the alien differences between childhood and adulthood, and how a member of one clan views, or more accurately, looks over then dismisses, members of the other:

The teacher took the window hook and pulled

fresh air into the classroom because we stank.

One kid hummed like Pig-

scribbly emanations. Another trailed

his two co-

As children we are at ease with our defects, with who we are. We make judgements but our list of attention-

When weekly bath nights locked into alignment

their eve would muster such a thickened funk

the teachers gagged. That was the power we had.

Another thing we kept between us and the world.

Paul Farley finds letting go of the past a sticky occupation. When he isn’t zooming in on childhood itself, he is still distracted by the obsolete, or the thought of regaining. He is aware of the level of reflection. Sticking to the school theme he advocates the need for a thousand lines: ‘I will not write nostalgic poems./I will put these things out of my mind.’

In ‘Big Fish’, a birth street is revisited, though the poem doesn’t offer much to sink your teeth into. That is left for ‘The Milk Nostalgia Industries’, a daft but pleasurable poem harking back to the times when the delivery of milk bottles to houses was the norm. He playfully revels in exaggeration. The word parlour, to him, yields:

Jane Austen sitting on a milking stool

with a natty teat technique; that and a pail

each jet rings into, soft lit, in an English field.

He conjures up a Milk Nostalgia Head Office, where it is possible to take a tour, to read the lost literature of the archived bottled notes, drink the milk of homesickness out of warm tetra-

my father was down there, blowing on the skin

of boiling milk to calm its head of steam,

and my mother carrying a glass lit from within

to bed. And then the gift shop, full of cheese.

The collection, Paul Farley’s fourth with Picador, has plenty of one-

But Farley does stray from the childhood and nostalgia themes lucratively for a time when he explores new ways of looking at the world around us. He admires the stars and becomes starlike himself in ‘Google Earth’, a poem about the virtual globe, where ‘there are never clouds/because the west wind of the Internet/blows silently down lost bus routes’. The gem though is the title poem, ‘The Dark Film’, where the sky is the star of the show, the city or town you’re standing in is the cinema and whoever is looking up to watch makes up the audience.

Unrated dark, two hours long.

We wonder where the film was shot:

the Night Mail stopped, or Empire State

caught midway through a power cut,

or if they’d left the lens cap on

and gone with it, declare it ‘art’,

or if this were a film at all

or leader-

We can’t help but let pessimism creep in. Is the beauty above us really meant for us, or will we be disappointed like so many times in the past? Like the book itself, the poem is full of anticipation, with the inevitable quiet and dull bits before the fireworks are let off and the horizon is lit:

and by the time the film has reached

the oilrigs and the inset isles

it crackles like a bonfire

and radiant fibres twitch and turn

to thistledown and stars, scratches

to flak, to Dolby bumps felt in

the gut, a tracer fire of dust,

then faces, looked at long enough.

Carl Griffin has been a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.