In an extract from his new book, the winding and wonderful, The Roots of Rock: From Cardiff to Mississippi and Back, Peter Finch explores the allure of Elvis, and the phenomenon that is the King’s tribute acts.

Elvis is on UK TV. It’s 1968. He’s dressed in all black leather like a motorbike rider, or a male Cathy Gale out of The Avengers. He’s come back. His sound is good, chilled then ripping up hot and rocking. But we don’t need him now. The man had his chance. We’ve got Led Zep and Jimi and Clapton. A rock journalist somewhere says that Elvis ought to get on a plane and come over here. That’s the spirit of the age. But he never does.

That NBC Christmas show was a creation designed to make Elvis relevant again, to put the King back on his throne. His myriad fans never countenanced that he’d left it. But the for the rest of us this jokey throwback looking like he ought to be out there manning rides at the funfair no longer held any kind of relevance. Good, yeah. But in the same way that Joan Baez’s run of great folk albums was completely capped by her wonderful Farewell, Angelina. This was released too late, late 1965, into a cold world where roots were giving way to fuzz fretboard pyrotechnics and the soaring, dope-driven extremities of guitar-driven rock.

Did Elvis have anyone there on wah-wah? Not really. He had Scotty Moore and Charlie Hodge in there on electric guitars but they played it straight.

By the time Elvis died in August 1977 the world had changed again. The convoluted depths of over-produced adult orientated rock had turned players back towards self-sufficiency. The working class had regained the upper hand. Three chord anthems once again dominated. Punk was on the streets. Despite his origins as a blue collar rocker Elvis was now, other than to his fans, about as relevant as Fred Astaire.

Not that Elvis fandom should be discounted. There were millions, still are. The diehards who had locked into the music of the King at some early point in their lives and were staying the course. Those graffiti-scrawled walls outside Graceland are testament. Elvis’s death is well documented. The hysteria. The copper casket. The miles of mourning fans in line each side of Graceland’s gates. Caroline Kennedy arriving to view the body. 80,000 fans lining the route up to Forrest Hills Cemetery. Fans killed in the crush to see the coffin, to touch the King. The misinformation. The sales opportunities. The Colonel’s onward plan. Then there’s the enduring legacy, mounting record sales and, even now, almost forty years later, a presence that won’t go away. There are conspiracy theories by the dozen. He did not die. He was abducted by aliens. He’s been seen working in a garage out west; in a tyre shop in Merthyr Tydfil; he’s retired and living as an old man on the warm west coast.

Not that Elvis fandom should be discounted. There were millions, still are. The diehards who had locked into the music of the King at some early point in their lives and were staying the course. Those graffiti-scrawled walls outside Graceland are testament. Elvis’s death is well documented. The hysteria. The copper casket. The miles of mourning fans in line each side of Graceland’s gates. Caroline Kennedy arriving to view the body. 80,000 fans lining the route up to Forrest Hills Cemetery. Fans killed in the crush to see the coffin, to touch the King. The misinformation. The sales opportunities. The Colonel’s onward plan. Then there’s the enduring legacy, mounting record sales and, even now, almost forty years later, a presence that won’t go away. There are conspiracy theories by the dozen. He did not die. He was abducted by aliens. He’s been seen working in a garage out west; in a tyre shop in Merthyr Tydfil; he’s retired and living as an old man on the warm west coast.

In Wales, you might have imagined his presence would have had a hold stronger than most. The south Wales valleys were still behind the fashion head by about ten years. They retained a love of Teddy Boy gear and the seat-ripping, flick knife wielding rock and roll that went with it. But it wasn’t quite like that. On the 16th of August, 1977 I was standing, browsing the lp racks at Buffalo Records on the Hayes in Cardiff. Buffalo was the place. For a record store it was large and it sold the sound of the seventies in its entirety. There were American imports and then bootlegs if you knew where to look. There was an atmosphere of youthful counter culture tempered by trade. Moving out of the racks were The Eagles and The Stranglers and Bob Marley.

The store was owned by David Marley and David Bassington and one of them turned off the slice of guitar rock that was playing as background to tell us that he’d heard it, Elvis Presley, he wasn’t making records anymore, he was sorry to announce but the king was dead. There was a moment of silence and then some gangly kid in spike hair and tartan bum flap shouted “Old fart” and the world’s bustle resumed. The music started up again and the death of one of the greatest in rock and roll was passed over as if it didn’t matter.

And he didn’t matter, either. Out there at music’s cutting edge. Old guards never do. But that didn’t stop the Colonel’s almost instant my boy’s gone but we’re going to capitalise like fury marketing campaign from putting Elvis’ 40 Greatest into the UK number one slot a month later.

In the UK Elvis was huge. In his day he was as big as the Beatles who were as big as Christ. The world, Kennedys, Khrushchevs, Thatchers and Regans notwithstanding, remained a rocking place. There was plenty of room for imitators and fellow travellers, the singers who had moulded themselves in his image: Ral Donner, Sonny James, Ronnie McDowell, Jack Scott, Cliff Richard, Fabian, Conway Twitty, and there were dozens more. These guys, or their managers, could see the money Elvis’s record sales were making and in the true pop music tradition engaged in imitation, recording songs the King might have made himself, just so they could earn a slice. The choice of repertoire was important. These singers did not record their versions of existing Elvis successes. They sought out songs that, had he heard them, might have got past the Colonel’s hard-handed repertoire control and been cut by Elvis himself. Fabian’s Turn Me Loose. Cliff Richard’s Move It. Conway Twitty’s Lonely Blue Boy and, for my money the best of all, Ral Donner with You Don’t Know What You’ve Got. That one was so Elvis-like you needed to double-check the label just to make sure who it actually was. When fashion changed these singers either faded or they shifted style. Cliff became elder statesman of British Christian pop. Fabian a teen idol film star. Conway Twitty the High Priest of Country Music.

But sounding like him wasn’t enough. For some singers they had to be the King. While he lived a small industry had grown up featuring several dozen Elvis impersonators. These ranged from Carl Nelson from Texarkana, Arkansas, who’d begun singing That’s Alright Mama pretty soon after Elvis had recorded it and built up a local following to a glut of Elvis sound and look-alikes who’d risen to fame after winning small town talent contents. In 1970, well before Presley died, the much troubled folk protest singer Phil Ochs had appeared at Carnegie Hall done up in a gold lame suit made for him by Nudie Cohn who had fashioned the Elvis original. In an attempt to be “part Elvis Presley part Che Guevara[i]” utterly unexpectedly he included an extended Elvis medley as a component of this new in your face Ochs[ii] act.

But sounding like him wasn’t enough. For some singers they had to be the King. While he lived a small industry had grown up featuring several dozen Elvis impersonators. These ranged from Carl Nelson from Texarkana, Arkansas, who’d begun singing That’s Alright Mama pretty soon after Elvis had recorded it and built up a local following to a glut of Elvis sound and look-alikes who’d risen to fame after winning small town talent contents. In 1970, well before Presley died, the much troubled folk protest singer Phil Ochs had appeared at Carnegie Hall done up in a gold lame suit made for him by Nudie Cohn who had fashioned the Elvis original. In an attempt to be “part Elvis Presley part Che Guevara[i]” utterly unexpectedly he included an extended Elvis medley as a component of this new in your face Ochs[ii] act.

These duplicate Elvises gained work filling-in on the circuit playing those places Elvis might have gone too had he been able to replicate himself. These were precursors to the Bootleg Beatles and the Stolling Rones, you knew that it wasn’t actually Elvis but you could dream.

After the 1977 death the world of Elvis impersonators significantly altered course. There was an immediate glut of work for those already on the circuit. Ral Donner narrated Presley’s voice for Malcolm Leo and Andrew Solt’s 1980s biopic This Is Elvis. Ronnie McDowell doubled as the singer for John Carpenter’s 1979 TV film Elvis. And the concert work also ramped up. Suddenly the world again wanted a slice of the King, sight of him, a touch of how he had been, a piece of his magic.

Impersonation was already stylised with performers selecting from a whole range of Presley periods and adopting the appropriate costume: the gold lame suit, the drape jacket, the jumpsuits, the American eagle cape, the Hawaii shirts, and, to new millennium eyes, the inordinately flared trousers. After the King’s death costume wearing went into overdrive and has pretty much remained so for the nearly 40 years that have passed since he left.

Presley costume is a fancy dress and stag party staple. Check the range of garb available at Amazon. Black Elvis bouffant wigs, white capes, great jewel-studded belts and full gold lame suits (made from plastic) can all be purchased for less than the price of a Best Of Elvis reissue.

Out on the circuit Elvis imitation began to change its character. It was no longer enough to make yourself look like the King. You had to become the man. Associations were formed, contests run, shows mounted. Impersonation became the realm of the amateur. Elvis Tribute Acts (ETAs) filled the paying stages.

Leslie Rubinkowski, who in 1996 spent a year trailing around America studying ETAs for her book Impersonating Elvis (Faber, 1997), reckons there to be 5000 out there in the USA pretending to be Elvis. Centrepiece of ETA activity is the long-running Images of the King contest staged in Memphis during Elvis week, August 10-16, the week of the fans’ Graceland candle-lit vigil, the week during which Elvis died.

Rubinkowski identifies a number of ETA characteristics. Performers are obsessives. They try to both dress and sound like the King. They study the films and adopt Elvis’s mannerisms, his walk, the way he stands. They mimic his facial expressions. If they can get there then they try to weigh just the same as he did in whichever period they have chosen to follow. They sing the songs. She reckons that she’s heard Polk Salad Annie more times that any decent human being should. The music becomes a sort of photocopy.

Rubinkowski identifies a number of ETA characteristics. Performers are obsessives. They try to both dress and sound like the King. They study the films and adopt Elvis’s mannerisms, his walk, the way he stands. They mimic his facial expressions. If they can get there then they try to weigh just the same as he did in whichever period they have chosen to follow. They sing the songs. She reckons that she’s heard Polk Salad Annie more times that any decent human being should. The music becomes a sort of photocopy.

Why do they do it? Academic Eric Lott who has researched the phenomenon, believes Elvis Presley impersonation to be almost exclusively an unstudied working class activity. If you can’t be black and hip then you can be a white Negro, you can be Elvis. “Like Elvis, I think I am a black man wrapped in white skin,” said Chicago impersonator John Paul Rossi. Lott calls it a “retro fantasy in postmodern garb[iii]”.

Most ETAs stick to the standard repertoire, but a small number transcend it. Listen to Robert Lopez who performs as El Vez and melds Elvis material with that of Mexico. The results can sometimes be astonishing. After a while of listening to this material and occupying its world the pleasures of reality can really beckon. The cutting excitement of those early Elvis Sun sides is so hard to replicate. You can sound just like it but generally you end up doing so minus the magic. Beyond is an Elvis world of increasing schmaltz, off message vocalising and instantly forgettable money-making songs that have survived only because the King once recorded them. You need to escape, get home and stick on some Beethoven or, better, the cutting tremble of Bukka White’s primitive vocal roar and his stinging slide guitar. Fixin’ To Die, yes.

I’m in Porthcawl now. That small town on Wales’ Glamorgan Heritage Coast which rose to prominence as a nineteenth-century coal port but is now a shabby seaside day out full of b&bs and cafes. This was the place where once the miners from the entire Welsh coalfield vacationed. That was back when coal was King and Benidorm was still to be discovered. There’s a fair, Coney Beach pleasure park, well there was. Today the place is undergoing a period of redevelopment. Around the site extend great fields of caravans linked by sand-filled roads. There are gift shops and bars and eateries and an enormous stretch of waste land now doubling as a car park. Glamorgan Heritage Coast be damned. Porthcawl is Caerphilly unbuttoned, Tonypandy on sea, the Rhondda with some sand but even more beer.

The Porthcawl Elvis Festival 2014 is now in its eleventh year. It is supported by a couple of local firms, Ace Taxis and Harris Printers, and is fronted by the founder of the Argentine Welsh Football Society, the distinctly non-Elvis look-a-like Peter Phillips. Without foreknowledge you might imagine the weekend to be one of musical reflection and historical recollection. An Elvis lecture perhaps. A session on Elvis’ blues roots. Stalls selling back catalogue and compilations of obscure b sides. Wall to wall showings of the King’s, with one or two notable exceptions, uniformly dreadful musical films. Not a bit of it.

As Eric Lott has suggested, Elvis imitation is almost entirely blue collar. And so, too, is Porthcawl, despite the golf links just along the coast. The women of a certain age who line dance in pink feather boas outside Dolly Parton concerts in Cardiff (see Chapter 25) are all here. So too, it feels, are the rest of what’s left of the middle-aged in the south Wales valley hinterland. As you walk around you pick up that valley buzz. Not a single accent seems to be anything else. The poet Robert Minhinnick whom I bump into on James Street outside the Sustainable Wales café, Sussed, which he helps run reckons the Elvis festival to be a “magnificent working class eisteddfod[iv]”. “It’s an excuse for drinking,” he tells me. “Same sort of thing as international rugby. You should see them go at it down around the Hi Tide, front of the amusement park, on Saturday night. Elvis staggering. They all are.”

As Eric Lott has suggested, Elvis imitation is almost entirely blue collar. And so, too, is Porthcawl, despite the golf links just along the coast. The women of a certain age who line dance in pink feather boas outside Dolly Parton concerts in Cardiff (see Chapter 25) are all here. So too, it feels, are the rest of what’s left of the middle-aged in the south Wales valley hinterland. As you walk around you pick up that valley buzz. Not a single accent seems to be anything else. The poet Robert Minhinnick whom I bump into on James Street outside the Sustainable Wales café, Sussed, which he helps run reckons the Elvis festival to be a “magnificent working class eisteddfod[iv]”. “It’s an excuse for drinking,” he tells me. “Same sort of thing as international rugby. You should see them go at it down around the Hi Tide, front of the amusement park, on Saturday night. Elvis staggering. They all are.”

Everyone is also dressed as Elvis. It’s hard to take in at first but every second person you look at is either wearing the full gold lame kit or sports enormous sideburns plus black bouffant hairpiece in imitation of the King at the height of his sartorial powers. And you don’t just dress as Elvis here if you are performing. The audience kit themselves out in tribute as well. Women dress in US Army uniform circa GI Blues or wear fifties style dresses, great flurries of petticoats and a rampage of polka dots. The men are often Elvis tribute tee shirted with false sideburns hanging from the arms of their fifties-style shades and with maybe a Blue Hawaii necklace of flowers draped round their necks. There are platoons of infantrymen in neatly pressed and considerably convincing US Army uniforms. And there are hosts of white-caped Elvis replicas. There are also a multitude of wigs. Real hair, synthetic bristle, some resembling pieces of carpet and loads in full plastic extrusion like shiny black helmets.

In one afternoon rambling the not yet quite autumn air of the seafront I spot Elvis singing on most corners and with further versions tributing the King inside bars, hotels and cafes. His fans are legion. I see female Elvises, smoking Elvises, overweight double the original at his worst Elvises, Elvis on a skateboard, pogoing Elvis, Elvis phoning home, Elvis on crutches, Welsh speaking Elvises[v], Elvis carrying three pints, Elvis fishing, Elvis at 80, Elvis in a wheel chair, junior Elvises, two of them trampolining in full caped regalia, Elvis surfing, Elvis as Lord Mayor wearing chains around his neck.

In fact the real mayor of Porthcawl, Phil Rixon, once asked the organisers what he could do to help the festival and ended up arriving by pink Cadillac and renewing his wedding vows in full Blue Hawaii dress at the film’s wedding scene recreation on the seafront.

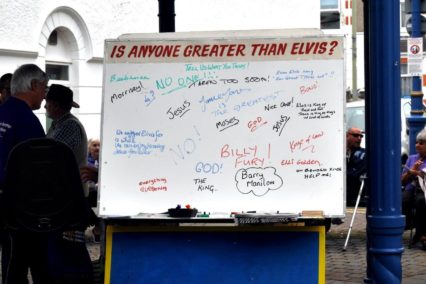

Amid all this Elvis hoopla what I didn’t see, even once, was anyone actually playing a musical instrument. I discount here the Gilgal Baptist Elvis preachers from the local evangelical church at the top of John Street who did have guitars but were singing Neil Sedaka numbers. They’ve got a white board mounted on a stand with the words “Is anyone greater than Elvis?” written across the top. They want passers-by to add “Jesus” and while the son of man does make an appearance he’s outnumbered by rival claims: Billy Fury, Bono, Morrissey, Barry Manilow.

Porthcawl’s Elvises are almost without exception karaoke men. There are a few ETAs who have made it through the heats and will appear in front of a full band in the who is best Elvis grand finale at the now distinctly ungrand Grand Pavilion. On the streets and in the bars, however, you look like the King, you sound like him, but you do it solo to backing tapes.

At the Hi Tide bar and diner complex at the beach edge there are four stages which offer a revolving display of ETAs. Audiences are huge and even at eleven in the morning well on the way to being rumbustiously pissed. We get Jimmy Elvis, Jamie Elvis, Karl Memphis, Ben Presley, Memphis Morgan, Elvis Melvis, Johnny Be Goode and Ponty Presley all doing their best. After a time the sheer weight of Elvis musical thump begins to deaden the mind. I’ve heard One Night so many times now that I can no longer tell it from Suspicion. I never want to hear Wooden Heart ever again.

On the sea front a pretty passable Elvis dressed in white drape and suntan has set himself up with laptop and amp driven speaker system. He’s asking for requests and after running through a few of the expected Elvis smashes, Ready Teddy and Guitar Man, a drinker in the crowd asks him to do something by Dion. “Dion? You mean Runaround Sue? That’s not Elvis. I can’t do that.” “Well sing it like Elvis would,” shouts the drinker. There’s no reply. We get It’s Now Or Never instead.

Would all of this have been going on if Elvis had not died when he did? I doubt it. There’s something about youth being taken away that parallels the King’s life with the lives of his fans. There’s also something about the way that Elvis didn’t write his own songs and wasn’t anything remotely near being termed an intellectual that appeals to his Porthcawl working class once coal mining fans. They remember the good times and want them back. Is that musical form, rock and roll, that drove itself up a side alley beyond which no progression was possible actually now be dead here in south Wales? By the Porthcawl evidence, certainly not.

taken from The Roots Of Rock From Cardiff To Mississippi And Back by Peter Finch. Published by Seren Books.

[i] Schumacher, Michael, There But for Fortune: The Life of Phil Ochs. Hyperion, 1966.

[ii] Ochs issued his Gunfight At Carnegie Hall in 1975. It contained both A Fool Such As I and a medley containing My Baby Left me, Ready Teddy, Heartbreak Hotel, All Shook Up, Are You Lonesome Tonight and My Baby Left Me. As Elvis impersonation it was dire but as a performance supporting Ochs’ position that the protest song no longer worked it was perfect. Ochs took his own life in far Rockaway, New York in 1976.

[iii] All The King’s Men by Eric Lott, from Race and the Subject Of Masculinities, Harry Stecopoulos and Michael Uebel (eds), Duke University Press, 1997.

[iv] Are You Lonesome Tonight in Island of Lightning, Minhinnick, Robert, Seren, 2013.

[v] In his book, The A-Z of Wales and the Welsh (Christopher Davies, 2000) Terry Breverton makes the claim that the Presley family came from the Preseli mountains in west Wales and were in fact Welsh-speaking themselves.