Nigel Jarrett takes a sideways look at the many plights of the publishing industry, its current status, and the effect on today’s writers.

Random House is falling down. Independent book publishers big and small are promoting a revolution that will make redundant their corporate relatives and the agencies which supply them with what they consider to be the best scripts. Already, literary agents are seeking other employment and self-published authors have won the undivided and almost exclusive attention of reviewers. For three years running, the Man Booker prize has been won by an author from a hitherto unknown and diminutive publishing house, in one case run by a clergyman from a former fisherman’s loft in Brixham.

The books pages of newspapers carry features about few other than the previously unknown. Self-published ‘classics’ are numbered in hundreds, while writers such as Martin Amis and Donna Tartt have announced their intention henceforward to switch publishers and write more online. Amis commented, ‘One could see the tide was turning. I wanted the tide to turn. The tide has turned. The tide. It has turned. Definitely.’

Well, not just yet. The foregoing is a spoof; wishful thinking eroded at the edges by accomplished fact, if only ever so slightly. Before exploring the detail of this turnaround-in-waiting, I should report a conversation I had a few weeks ago with the author of six books, none of which has passed beneath the snout of an agent or polluted the perfumed atmosphere of a publisher’s office. He wrote the scripts, got them turned into professional-looking paperbacks, lodged them with Amazon, and sold them, picking up reviews from readers, which, he says, have resulted in further sales. He’s not interested in profits, prizes, or the blandishments of the Times Literary Supplement. He just wants his books made available and then read. He’s a prolific author with a following, but not as we normally understand it. The books would by any measure be regarded as ‘literary’.

We might have expected vapid examples of the Horror, Sci-Fi or Fantasy genres, which abound on Amazon-style sites; instead we have long words, crisp sentences, no middles, no ends – and references to Voltaire. One reader, an academic living two hundred miles from the author in Huddersfield and unknown to him, said the books reminded her of something by Don DeLillo out of Tom Wolfe. So, no crap.

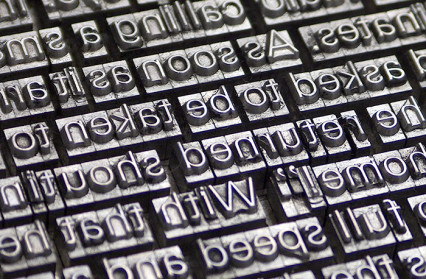

That writer’s former hobby was collecting rejection slips from publishers and agents. Their accumulation over a decade didn’t dissuade him from writing, or – a self-confessed mistake, this – from wondering if his detractors were right and he probably misguided. He never got it ‘right’, so he abandoned this traditional method of publication. Here, it’s pertinent to say something about vanity publishing. Drowning in rejections and infected by incurable amour-propre, our author might have decided to pay for his masterpiece to be published. There were plenty of firms willing to do that for him. In exchange for, say £500 up front, they would print thirty copies bound in imitation leather and send them to him in a parcel. The books’ contents might be unedited, unproofed, and shoddily typeset. Not to worry. He could have sold them to friends and family. If anyone else wanted a copy – tough; the firm, if it had not ditched the original template, might have charged £50 or more for each additional volume, pleading ‘economics’, the vanity publisher’s euphemism for, ‘Make yourself scarce; we’re working on someone else’s more lucrative book now.’ Such companies still exist, though they’ve been embarrassed into silence or a willingness, while keeping their heads down, to point out their limitations. Besides, these days they operate in the shadow of the self-publisher, which is what our author became.

The difference, etymologically no difference at all, between vanity publishing and self-publishing is one of value for money. The self-publisher – in reality the person who produces the publication – will edit, proof, register, typeset, design, market, promote and sell the book. That’s the theory. In practice, there is no way of questioning the standard or efficacy of these activities before they become obvious, to third parties if not to the author. But multitudes of writers are opting to take advantage of them. At the very least, they remove the possibility of rejection through established channels. The advent of website retail marketplaces such as Amazon, Ingram and Nielsen means that the book is where the whole world can get at it. How anyone discovers it’s there, however, is a cyberspatial mystery, but the power of social media should not be under-estimated.

As if anticipating these new procedures, digital printing has thrown up companies who will print on demand, obviating the need for a physical and costly print run. Remaindering is what happens when a print run fails to sell completely. The cost of a 300-volume run would make self-publishing prohibitive, whereas print-on-demand initially results in no books: they appear only when someone orders them. The ‘self’ in ‘self-publishing’ refers to the authors, who pay for the books to be made. Apart from writing and submitting the script along with the cheque, and with no possibility of rejection, ‘oneself’ is exercising vanity by any other name. The old vanity was unpredicated self-conceit; the new vanity is enlightened self-interest, the enlightenment stemming from the realisation that the old methods seem to be guaranteeing continual rebuff but no longer represent the only way forwards. Maybe that’s not vanity at all.

At stake here are the estimate and hierarchy of literary worth. To be rejected by Faber or Cape or Chatto & Windus but accepted by the Haywain Press from Newbury or Scavenger Editions from just outside Oldham is, some might say, to be put in one’s place and for one’s book to be lodged in some kind of inferior league of achievement. Ten years ago neither Haywain nor Scavenger would have sent copies to the TLS or the Literary Review with any hope of an acknowledgement let alone a notice, however minuscule. But the Guardian recently published an article devoted to an Irish literary ‘renaissance’. The work of the authors featured did not constitute much of a stylistic rebellion but it did suggest how many writers, following multiple rejections, were turning to publishers in Newbury and the perimeter of Oldham – and Derry and Co. Clare.

In any case, the review pages of national journals have for a long time been reviewing fiction published by relatively obscure houses. (The best poetry in Britain is being brought out by small operators, Oxford University Press having long given up on it and the few remaining heavyweights for ever wondering whether or not to follow suit.) Books from these publishers are also moving closer to bagging more of the glittering prizes. This is because, by law of averages, the spread of scripts over a wider area is bound to result in many of the most illustrious turning up in far-away places. For so long occupying the territory of a writer’s fall-back position, they are now first choice. Why shouldn’t they be when it’s become almost impossible for any but the brightest and luckiest to find an agent, let alone a publisher? It’s not that simple, though.

Self-publishing can also mean that writers on their own accomplish all the tasks for which a ‘neo-vanity’ publisher is paid. It’s hard work and has a vanity quotient of its own: as a former newspaper sub-editor I know that no reporter’s copy was perfect but that every reporter thought it was. It takes honesty to find someone who will say that one’s script needs re-writing and courage to abide by the decision. But it’s possible and it needn’t be costly. Promotion and marketing would have to be modest. Sales might or might not ensue in appreciable numbers, and the relative ease with which a book can be brought out means that the market is flooded with titles.

In 1998, to pick a year at random, over a million books of all kinds were published in Britain. That said, and as a result of the new opportunities, more writers than ever before have found their way into print, though in a sense things haven’t become easier. Haywain and Scavenger are now receiving, increasingly from agents, more submissions than they can handle – say, a hundred scripts a week when they publish only six titles a year. Rejection by them after the bum’s rush from Bloomsbury has forced many into self-publishing of both kinds: the third-party, appeal-to-vanity sort or, if that’s too expensive (actually, it’s not a wallet-burner), the route leading to strict DIY. None of this takes into account the possibility of publishing on screen without a print alternative. The levelling-out of Kindle sales, reported in the last few weeks, is just a slip from the over-active to the healthily upbeat. Amazon is not much worried.

One of the consequences of this glut is the reluctance of some reviewing outlets to consider noticing any book whose production has been paid for partly by the author. That makes sense only in practical terms: it’s impossible to review everything, and paid-for titles might be considered inferior or flawed by definition. The riposte is easily argued. If one were told belatedly that a long-celebrated book had been part-financed by the author, would it fall in one’s estimation? Of course not. In any case, there are plenty of examples of distinguished self-published books, and the internet simply facilitates their further production.

One prognosis of this cultural shift views the already sterile position of the bestseller and the Bestsellerdom it inhabits as becoming less and less meaningful than their replacement by a series of discrete, archipelagic literary events sufficient unto themselves but liable to travel geographically by word of mouth or by viral ignition in cyberspace. This is already a feature of regional writing – ‘regional’ in the non-pejorative sense. Irish, Welsh and Scottish literatures have never been less than self-sufficient. That they have grown in importance as a result of internet dissemination is unquestionable.

The Welsh example, and possibly the others too, is of course complicated by subvention. Welsh independents committed to publishing serious literary work would be either producing something completely different or out of business if they were not supported by public funds disbursed through the Welsh Books Council and formerly by the Arts Council of Wales. That begs questions about the procedures by which one writer’s work is deemed worthy of a grant (and publication) while another’s isn’t. Furthermore, there are some independent Welsh publishers who cannot afford their titles to be handled by the WBC, with its marketing and promotional reach but also its commercial necessities. One suspects that even indie publishers grant-aided by the WBC are expected to conform to some kind of realistic business model. More than one bookseller has asked these independents for copies of new titles to sell in shops at the usual wholesale rates, only to discover that they’re not discounted enough. So, no deal. Thus is the publisher obliged to advertise, and implore writers to take to the road and sell their books themselves. All writers have to do that to a greater or lesser extent, though the better-known ones are mostly putting in appearances.

Among today’s cataract of titles, there’s as much dross coming out of the major London houses as there is lamentable rubbish spawning along the internet as a result of self-publication. One of the reasons why desktop publishing, its earlier manifestation, did not catch on straight away was fire-fighting by the corporates. They knew that before long writers would be into competent book production without intermediaries, and they wanted to postpone it. Well, now writers are. It’s just that there’s probably more chaff than wheat around at the point of publication. Winnowing, always an essential and eternally ongoing exercise, has in part been rendered superfluous by the frantic production of chaff. Readers choose.

The Fall of the House of Random might be a good title for a book. It’ll certainly be one that charts how book-publishing everywhere is changing and how the small fish are making an ever noisier commotion among the bigger lords of the pond, whose domain might be wide but is not bottomless.

There’s always a danger that the upstarts will be regarded as an additional food source. Then again, lording it over such a non-subservient increase in population will be that much more difficult and, perhaps, ultimately impossible.

Nigel Jarrett contributes to Wales Arts Review on music, books and other subjects. He is a winner of the Rhys Davies prize and the Templar Shorts award for short fiction. A former daily-newspaper journalist, he reviews for Jazz Journal and writes a column for it called Count Me In. His sixth book, a fictional memoir titled Notes From the Superhorse Stable, appeared this month from Saron Publishers; later this year, his fourth story collection, Five Go To Switzerland, will be published by Cockatrice Books, based in north Wales. In August he is Author of the Month for the National Library of Wales’s digital libraries project.

____________________________________________________________

Recommended for you:

Emma Schofield introduces a new series from Wales Arts Review looking at a 100 page turners of Wales, a vast exploration of Welsh fiction that uses the BBC’s recent “Novels That Shaped Our World” as a springboard to argue that Wales’s rich and exciting literary output over the eras has produced a long list of exciting, engaging, and thrilling reads.

____________________________________________________________

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.