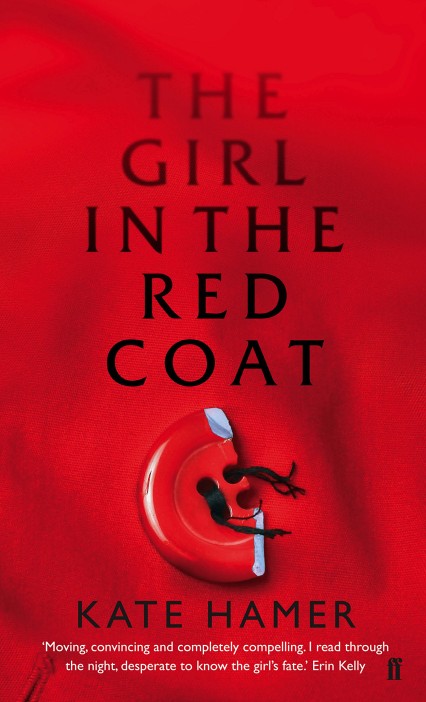

378 pages. Faber and Faber, £12.99

The Girl in the Red Coat is that rare thing: a book that manages to be both a highly considered literary novel and a page-turner of the highest order. It exhibits a lucid, poetic prose style that teems with penetrating observation but it is also one of the most compulsively readable books that will be published this year. In its almost old fashioned dedication to plot and reader-enjoyment it most obviously calls to mind Donna Tartt – a writer that Hamer has said she admires – but where Tartt can sometimes appear to sacrifice prose style for the sake of plot, Hamer handles the tightrope walk between the two with consummate ease. To say that there is also more than a touch of the Angela Carter of The Magic Toyshop – and even, perhaps, the Nabokov of Pale Fire – is to give an indication of Hamer’s successful interweaving of fairy tale with grim reality.

The Girl in the Red Coat is that rare thing: a book that manages to be both a highly considered literary novel and a page-turner of the highest order. It exhibits a lucid, poetic prose style that teems with penetrating observation but it is also one of the most compulsively readable books that will be published this year. In its almost old fashioned dedication to plot and reader-enjoyment it most obviously calls to mind Donna Tartt – a writer that Hamer has said she admires – but where Tartt can sometimes appear to sacrifice prose style for the sake of plot, Hamer handles the tightrope walk between the two with consummate ease. To say that there is also more than a touch of the Angela Carter of The Magic Toyshop – and even, perhaps, the Nabokov of Pale Fire – is to give an indication of Hamer’s successful interweaving of fairy tale with grim reality.

The plot revolves around the abduction of an eight-year-old girl at a children’s storytelling event and the subsequent harrowing trauma that this exerts both on parent and child. Indeed the heart of the novel is the relationship between Carmel, the missing girl, and Beth, her mother. ‘Courage. Carmel. Courage’, Beth had used to say to her daughter and the young girl holds these words close to herself throughout her terrible ordeal. She also hangs fiercely onto her name when her fundamentalist Christian abductor tries to make her change it to ‘Mercy’. These are some of the most affecting sections of the book, when Carmel – whose voice is even beginning to adopt the American intonations of the abductor – can feel her old self drowning in front of her very eyes; when she can almost feel herself forgetting the person that she used to be:

I start talking and I say it real fierce. I have to say it before it all gets forgotten.

‘This is what you must remember. My name is Carmel Summer Wakeford. I used to live in Norfolk, England. My mum’s name was Beth and my dad’s name is Paul. My mum had a glass cat that she kept by the bed …I lived in a house with a tree by the side and a spider’s web by the back door … My name is Carmel. My name is Carmel Summer Wakeford.’

Both mother and daughter take it in turn, chapter by chapter, to tell their side of the story, and Carmel’s side, especially, helps to lend the book its slightly unreal, fairytale-like atmosphere – simply because we see everything through the eyes of an eight year-old that is alert to the inherent mystery of the world. As the novel develops, however, and the little girl becomes a worldly teenager that shows no sign of being reunited with her parent, her voice changes, becoming more and more dislocated and confused. Carmel starts to forget her childhood, almost as though it had been a fairy tale that she had told herself to fend off loneliness. The Girl in the Red Coat is a very subtle and moving novel in this respect because for all the ‘will Carmel be found?’ thriller-style aspect of the book, at its heart this work is primarily concerned with the mind-warping loneliness that both Carmel and Beth experience without each other.

Indeed Beth’s breakdown, retreat into numb despair and slow recovery are handled with such aplomb by Hamer that you imagine that she must have researched the subject of child abduction thoroughly. When I recently interviewed her for a future Wales Arts Review feature, however, Hamer said that she deliberately didn’t want to research famous abduction cases out of respect to the real life families involved. Rather, as a mother herself, she tried to imagine what the reality of such a situation would be like – a fitting approach for a book that celebrates the indomitability of the human spirit, the power of the imagination and the deep, almost mystic importance of words.

The Girl in the Red Coat is that rarest of things, a compulsive page turner that attains the emotional profundity and the psychological reach of poetry. It is a book that unquestionably serves notice of a remarkable new talent.

photo credit: Mei Williams