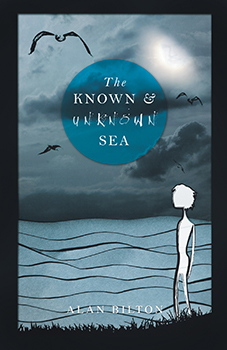

Cillian Press, 216pp

The Known Sea is a real place – albeit not a watery one – on the moon, as are the other places used as section headings in Alan Bilton’s second novel. And yet for readers of the book – for whom amongst us has travelled to the moon? – these places are unknown. Except, of course, in our imaginations or our dreams. And there we have it. In the same way as story tellers can give a familiar tale any ending they choose, so we all can and do reinvent our worlds to help us through life’s perilous journey.

The Known Sea is a real place – albeit not a watery one – on the moon, as are the other places used as section headings in Alan Bilton’s second novel. And yet for readers of the book – for whom amongst us has travelled to the moon? – these places are unknown. Except, of course, in our imaginations or our dreams. And there we have it. In the same way as story tellers can give a familiar tale any ending they choose, so we all can and do reinvent our worlds to help us through life’s perilous journey.

Alex, the young (how young we are not told, but I would say for most of the book under eight years) narrator of The Known & Unknown Sea, tells us the story of his world, the one he lives in inside his head during an unpredictable and uncertain time. His life is also located in the real world, or shall we say the world of shared expectations.

So let us begin at the beginning, for there are shades of Dylan Thomas’s Llareggub in the place where Alex lives with his family, a seaside town in which the houses are ‘higgledy-piggledy as if dropped from a great height’, which we can easily envision as being in Wales, especially as many of the characters have Welsh names. The novel opens with a mystery: Alex, his mother, his father, his brother Mikey and certain others have received unsolicited tickets for a boat to the other side of the bay, a bay which is always shrouded in mist, through which only vague shapes can be seen. How that phrase ‘the other side’ is redolent with meaning. Alex does not know what it means and people tell him different things, but it is surely not coincidental that setting off across the water entails mortal danger. Illness pervades the journey from the start. Mikey asks about ‘the sickness’, ‘There were rumours of people falling ill right across town’ and Alex himself is ‘peaky’ from the start.

But such worries are apparently cast aside in the feverish excitement of the preparations. The family gathers in Grandfather’s front room to decide ‘what should be done.’ In the opening scene we meet Alex’s three grandmothers, who ‘all wore black and sat together like a tea-cosy with three spouts – Granny Dwyn, Granny Mair, and the other one.’ To which – if any – of these Grandpa is attached Alex does not know, but they all decide to stay and look after him after an unfortunate accident in which he is knocked out by a case ‘full of pictures of pretty ladies who looked very nice but were, in fact, indecent.’

I was rather sorry to say goodbye to these colourful characters so early on in the novel, but the author has a clever device for keeping them and other members of the extended family within the narrative, as Alex calls to mind the things they say, their vivid descriptions and turns of phrase. So, for example, Bethan the small girl who appears on the boat, is ‘Smaller than a gnat’s hankie’ (Uncle Glyn), and the ceiling of the metal box under the funnel of the ship which Bethan dares Alex to slide down is ‘Lower than a dachshund’s balls’ (Cousin Gareth).

As he progresses down this version of Alice’s rabbit hole, Alex discovers his Grandpa behind frosted glass in some kind of sick bay. Why is he there? Where is there anyway? When the boat reaches the other side Alex and his family go to a hotel called the Hotel La Luna, or is it something else? Scenes shift, things transform, there is an excursion to a crater and large quantities of food which Alex greatly enjoys.

Meanwhile, the boys’ parents are troubled and sad. His mother reads Russian novels and cries a lot; his father is taken off, as Alex is told, or imagines he is told, ‘to work on the new resort.’ There is snow, but it has a different chemical composition and is cobalt blue or purplish. There is mention of wearing special shoes. What is the mysterious sickness? Somehow Chernobyl comes to mind, though this is my imagination playing off what is in the book. Or are these shoes you need to walk on the surface of the moon, that place where Alex feels he could be ‘free from this world’.

Bilton is a great admirer of the writer Kazuo Ishiguro, and considers his 1995 novel The Unconsoled the greatest British novel of the late twentieth century. Ishiguro’s book is the nearest thing I have read to the actual experience of being in a dream. Given Bilton’s own experimentation with writing about the dream state his admiration for this book does not surprise me. There are, however, difficulties for the reader. In our own dreams, in which we are taken here and there without any logic to the twists and turns of the dream’s plot, we are held hostage, we must follow. Not so in a novel. It is difficult to stick with the changes of scene. I have tried twice to read The Unconsoled, but have not yet completed it. In The Known & Unknown Sea the journey is much shorter and there is no reason to give up on it, but I find it difficult to see it clearly, to form a sequence of pictures in my head. Yes, there are some vivid stills, such as Alex’s vision of the stars, ‘this great milky spray, like cream on the fur of a big black cat,’ but other scenes fail to come into focus.

The set-up of this novel is beautifully realised and perhaps, as the author has admitted himself in a discussion about his work, putting characters into such a magically mysterious setting is always going to be disappointing. But it is not the characters that disappoint, but the difficulty in engaging fully with the dream/fever journey of the child narrator. There is nothing wrong with mystery and ambiguity, indeed many (including myself) actively seek such elements in their reading, and while I did not find this novel completely satisfying, it certainly engages the imagination, populated as it is with such a rich cast of characters and their sea of voices.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.